Last month Seven Score and Ten posted a humorous story about Confederate troops near Pensacola having a funeral procession and ceremony to bury some bad beef. I respected the equanimity of the Confederate troops and their ability to make lemonade out of the lemons in their menu. On the other hand, Northerners from my neck of the woods could be downright surly when it came to the food they were being served.

[On May 14, 1861 the group of volunteers (predominantly from Cayuga County, New York) that we’ve been following officially became the 19th Regiment of New York Volunteers and elected officers. On May 22nd the regiment was mustered into service for the United States. The drilling was dreary work because early May was “cold, raw, rainy, and muddy” and there were still no proper uniforms. There was little relief at mealtime.]

While the Cayuga men bore mud, bad weather and thin clothing without a murmur, one item in their experience they revolted at. Fresh from comfortable homes and tables spread with the snowiest of linen, bountifully supplied with appetizingly cooked meats and vegetables and fragrant decoctions of Java and Young Hyson, with cream and a more or less wide array of delicacies, the volunteers found the transition to corned beef, salt pork, boiled potatoes, soft bread, mush, clear coffee and machine made hash, which formed their soldier’s ration, rather severe. It was a forty-five cent ration, too, — a princely one for soldiers. Many a time afterwards were the men thankful to stay raging hunger with even a five cent handful of inhabited hard-tack. But in

Elmira they were slow in getting used to it, even with appetites

sharpened by long drills.

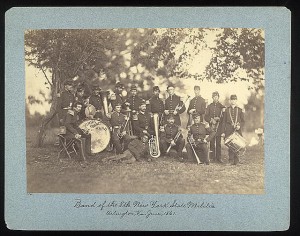

Hash was one of the staple articles of food. It was prepared in the shanty in the corner of the Barrack yard, used as a cook house by the contractor. What old 19th boy does not remember the hash machine? That devourer of scraps was going, with noisy clatter, day and night; trains would thunder by on the railroad with a roar ; brass bands would fill the air with martial strains ; the cheers of the soldiery would shake the ancient buildings ; but nothing would ever drown the steady music of the hash machine.

For some days the meat, and occasionally the hash, had been of a character to excite the alarm of olfactories. The hash was sometimes burnt. One day a volunteer discovered in his ration something which he swore was the end of a dog’s tail, the fur still on. Waving the obnoxious chunk aloft on his fork, he went down the mess room showing it to his comrades. The yard, soon after, was full of excited soldiers. Several circumstances occurred to fan the rising flame of discontent against the contractor. A moment more and there was a terrific shout. The cook house was tumultuously invaded. An avalanche of men sprang in through the delivery windows, amongst the cheers of a crowd outside, driving out the occupants pell mell. The

hash machine was banged and smashed to flinders, and then there followed a general raid on the whole establishment. Stumbling, as he came in through the window, one volunteer plunged feet first into a barrel of eggs. Covered with yolk to his ears, he emerged a fearful looking apparition, but, undaunted, made for three other barrels of the same commodity. These also he overturned and smashed. A huge darkey stuck his head in the door. A volley of eggs and chunks of meat saluted him; he retreated precipitately. Two barrels of soft soap were

tipped over, and beans, mush, hash, potatoes and meat flew in every direction. The establishment was completely turned topsy-turvy and the volunteers returned to their quarters. Some of the men were sent to the guard house for this affair; but the regiment had better rations after it.

From Cayuga in the Field by Henry Hall and James Hall.

Well, there was allegedly a furry dog tail in the hash.

You gotta be kiddin’ me!

Wikipedia offers a possible explanation of what Henry Hall meant by “inhabited hard-tack”:

During the American Civil War, 3-inch by 3-inch hardtack was shipped out from Union and Confederate storehouses. Some of this hardtack had been stored from the 1846–8 Mexican-American War. With insect infestation common in improperly stored provisions, soldiers would break up the hardtack and drop it into their morning coffee. This would not only soften the hardtack but the insects, mostly weevil larvae, would float to the top and the soldiers could skim off the insects and resume consumption. Another way of removing weevils was to heat it at a fire, which would drive them out. Those troops too impatient to wait would simply eat it in the dark so they wouldn’t have to see what they were consuming.[

The Pensacola beef was buried; the hard-tack weevils rose again.

A description of the hard-tack photo is here.

Pingback: “Shabby Gray” Gray Review? | Blue Gray Review

Pingback: No Saloons In Sight | Blue Gray Review