And a fatalism like Napoleon’s

On May 25, 1862 Stonewall Jackson’s Confederate army won the First Battle of Winchester. As The Civil War 150th Blog points out Jackson had “had become a national hero”. Here’s some evidence for that from the Richmond Daily Dispatch May 31, 1862:

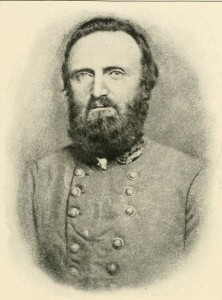

Memoir of Gen. T. J. Jackson.

A friend of this illustrious warrior, whose deeds are now resounding from one end of the Confederate States to the other, has enabled us to give the following sketch of his life, previously to his acceptance of a command in the Confederate army. Since that time it has become a part of the history of the country.

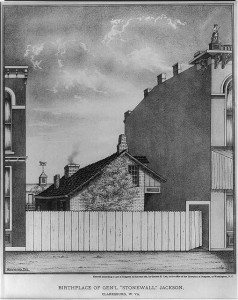

He was born in Clarksburg, in the county of Lewis, in the year 1862, of highly respectable parents, both of whom died during his infancy, leaving him without a cent in the world. During his early childhood he resided with an uncle, whose name we did not hear and at the age of sixteen he had conducted himself so well, and produced such a favorable impression of his energy and integrity that he was chosen constable of the county. In the year 1842 a cadet had been appointed from his district to West Point, who declined to go. Jackson immediately conceived the idea of filling the place he had left vacant. Our informant says, that one day. while it was raining exceedingly hard. he burst suddenly into his office, the rain streaming from his clothes, and told him that he must give him a letter to Mr. Hayes, at that time representative in Congress from the Lewis district. Upon being asked what he wanted with such a letter, he replied he wished to go to West Point. His friend pointed out to him what he regarded as the absurdity of such a scheme, seeing that he was very deficient in education, and would, therefore, probably not be able to stand the preliminary examination. He acknowledged the alleged deficiency, but said he was sure he had the perseverance to make it up. He obtained the letter without further difficulty, and that very evening borrowed a horse, under promise to send him back by a boy whom he carried with him, and rode to Clarksburg to take the stage. It had been raining for weeks as it can only rain in that country, the roads were muddy as they are muddy nowhere else that ever we heard of Jackson arrived in time; but on account of the muddy roads, the Postmaster had furnished the mail an hour before time, and the stage was already gone. With characteristic fidelity to his promise, Jackson sent the horse back, instead of riding him on in pursuit of the stage, and took it on foot through the mud. After a run of thirteen miles, he overtook the stage, jumped in, went to Washington all muddy as he was, presented his letter to Mr. Hayes, and was by him, intern, presented to the Secretary of War, who gave him the coveted warrant. At West Point he severely felt the want of early education, but his indomitable spirit overcame every obstacle. He was never marked for a demerit during his four years, and graduated with the class of 1846, the same in which McClellan graduated.

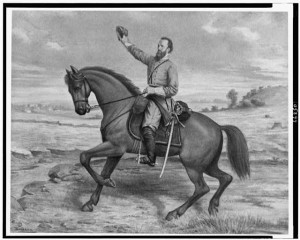

The young graduate was ordered off immediately, with the rank of Second Lieutenant, to join General Taylor’s army in the Valley of the Rio Grande. He arrived after the battles of Palo Alto, Resaca de la Palma, and Monterey, and before that of Buena Vista was ordered to join General Scott before Vera Cruz. At the siege of this latter place he commanded a battery, and attracted attention by his coolness and the judgment with which he worked his guns, and was promoted First Lieutenant. For his conduct at Cerro Gordo, he was brevetted Captain. He was in all Scott’s battles to the city of Mexico, and behaved so well that he was brevetted Major for his services. On one occasion he commanded a battery upon which the fire of the enemy was so severe that more than half his troops, who were raw, incontinently ran. Jackson was advised to retreat; but he said if he could get a reinforcement of fifty regulars, he would take the enemy’s battery opposed to him, instead of abandoning his own. He sent for the named reinforcement, but, before it came, he had already stormed the obnoxious battery.

Jackson’s health was so much shattered by this campaign that he was compelled to resign. He accepted a professorship at the Military Institute, where he continued until the secession of Virginia. In height, he is about six feet, with a weight of about one hundred and eighty. He is quite as remarkable for his moral as he has proved himself to be for his fighting qualities — being a perfectly conscientious man, just in all his ways, and irreproachable in his dealings with his fellow men. It is said he is a fatalist, as Napoleon was, and has no fear that he can be killed before his time comes. He is as calm in the midst of a hurricane of bullets as he was in the pew of his church at Lexington, when he was professor of the Institute. He appears to be a man of all most superhuman endurance. Neither heat nor cold makes the slightest impression upon him. He cares nothing for good quarters and dainty fare. Wrapped in his blanket, he throws himself down on the ground anywhere, and sleeps as soundly as though he were in a palace. He lives as the soldiers live, and endures all the fatigue and all the suffering that they endure. His vigilance is something marvelous. He never seems to sleep, and lets nothing pass without his personal scrutiny. He can neither be caught napping nor whipped when he is wide awake. The rapidity of his marches is something portentous. He is heard of by the enemy at one point, and before they can make up their minds to follow him he is off at another. His men have little baggage, and he moves, as nearly as he can, without encumbrance. He keeps so constantly in motion that he never has a sick list, and no need of hospitals. In these habits, and in a will as determined as that of Julius Caesar, are read the secret of his great success. His men adore him, because he requires them to do nothing which he does not do himself, because he constantly leads them to victory, and because they see he is a great soldier.

I don’t think The Dispatch article is 100% factual, but Jackson’s willpower and opportunism are displayed. For example, one way or another, he found a way to get to West Point when he saw his chance.