According to a reprinted story in a Southern newspaper, Indiana Governor Oliver P. Morton criticized the idea of an armistice in a speech to returning veterans during a year in which he was up for re-election. He claimed that the only way the South would ever return to the Union was if the North agreed to pay all the South’s war costs and amended the federal constitution to allow secession, which would eventually make Northern abolition states secede.

From the Richmond Daily Dispatch September 9, 1864:

A Northern View of an armistice.

At Indianapolis, on the 29th ultimo, there was a grand reception of several returning regiments.–Governor Morton made an address to the soldiers, in the course of which he discussed the question of an armistice as follows:

“It requires two parties to make an armistice; and Jeff. Davis has already declared that he demands the withdrawal of our armies from the South as a necessary preliminary to any negotiation. Who shall ask for an armistice. Shall our Government sue for terms at the feet of the South? Will this audience of soldiers agree to that? [Cries of “No! No!”] But what does an armistice mean? It means to cease operations in front of Atlanta; it means to loose the hold on Richmond; it means to stop Farragut at Mobile.

“As every one knows, diplomacy takes a great deal of time, and probably, at last, would fail. Can we spare enough of the weather now left us for military operations to be frittered away in armistice, and then find ourselves carried into the winter, when our campaign must necessarily close? Can we afford that now? But who believes the rebels will voluntarily come back into the Union, and give up those very ideas for which they have suffered the horrors of a long and bloody war, especially if we are to acknowledge, by asking an armistice, that we are unable to conquer them?

“Can we coax them back! If we try that, we shall have to agree to pay their war debt; to give a pension to their widows and orphans and maimed soldiers; we shall have to pay the damage that has been done to the Southern States during the war; and, more than all, we will have to engraft into our Constitution the doctrine of secession. Suppose we succeed. When we come to voting money to pay the war debt of the South, or to pension their soldiers, or to reimburse them for damages, abolition Massachusetts, abolition Ohio, abolition Wisconsin, will tell us, “We did not want an armistice, we wanted to fight this war out; but, as you have acknowledged secession in your Constitution; we will quietly walk out.” In this way the Union would go to pieces, and the country we tried to save be broken up by the very compromise that was intended to preserve it. We can make no compromise but what will break up the Government. The only way to get out of the war is to fight it out. (Applause.)

“But these peace men say the North is exhausted. Are we exhausted? The cost of this war is not one-half of the profits of the country. We have never been as wealthy as now, and there are three millions of men in the North who have not yet shouldered a musket in this war. Are we exhausted? General Grant has the rebellion by the throat in front of Richmond, and the General has told a United States senator that he would not let go his hold even if New York, Philadelphia and Washington should be burned. Sherman is all right at Atlanta, and we will crush this rebellion if we are not pulled off by the traitors of the North.”

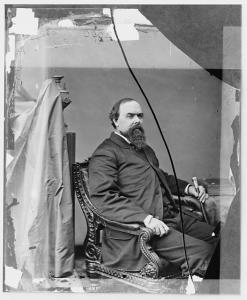

Civil War Home summarizes Mr. Morton’s tenure as a strong pro-war governor:

A skillful political opportunist, Morton emerged as the most powerful and, by some estimates, the best of the war governors. He answered Abraham Lincoln’s call for troops by raising twice the number requested for Federal service. Certain the war would be brief, he labored to keep in uniform every Indianan who volunteered, so that none would be prevented from serving when the War Department began refusing troops it was unprepared to feed and equip. Largely because of his efforts to encourage volunteerism, Indiana provided 150,000 enlistments to the Federal army with little resort to the draft.

The governor generally backed Lincolns war measures, though he complained about excessive military arrests, resisted the draft, and opposed freeing Southern slaves until the president issued his emancipation proclamation 1 Jan. 1863. Jealous for his states prestige in the Union, he also clashed repeatedly with Federal authorities in his determination to prevent other states from being treated more favorably. He waged a bitter campaign against Copperheads (Peace Democrats) and when growing peace sentiment pitted him against a legislature threatening to limit his military powers, rather than call the hostile representatives into session Morton kept the state government running with loans from Washington, advances from the private sector, and profits from the state arsenal he had established. In 1864 he was reelected along with a Republican legislature, in part by arranging to have 9,000 sick and wounded Indiana soldiers furloughed home in time to vote.

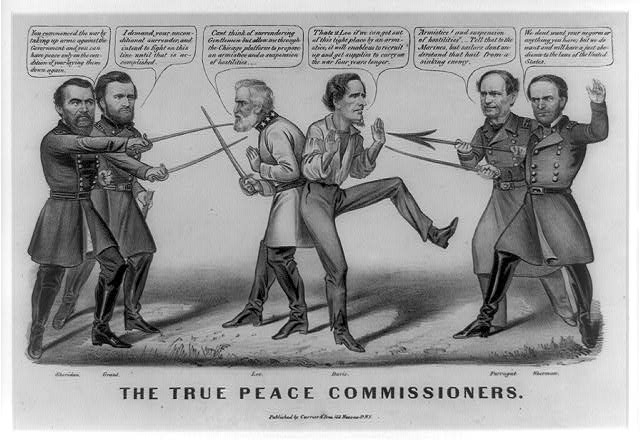

The following political cartoon from 1864 puts the “armistice” word in the mouths of General Lee and President Davis: