On February 22, 1865 “Tennessee voters approve a new state constitution that abolishes slavery”[1] According to this report, on the same day that President Lincoln was shot, black men in Tennessee petitioned the state senate for legal rights. Freedom wouldn’t mean too much if wicked men could prey on those defenseless under the law. If the freed blacks knew their property rights would be protected they would be more industrious and persevering.

From The New-York Times April 25, 1865:

The Colored Men of Tennessee Ask for Legal Rights.

In the Tennessee Senate, on the 14th instant, Mr. PEART submitted the following petition from the colored men of East Tennessee, remarking that while he did not indorse all its contents, the main portion of it was advantageous to both the black and white men of our State. There may be a disposition by some of the young members to avoid the responsibility of acting on it, but I think it should be fairly and promptly dealt with, without any equivocation:

To the Senate and House of Representatives, assembled:

We your humble petitioners ask you to hear our grievances, and we believe you will. You have done such noble acts so recently, that we are induced to believe your hearts are stirred to deeds of right, justice and humanity, in abolishing slavery in this State, this you have done without our asking you. Now we ask you to extend the protection of law to us, that we may be of some use to ourselves as well as society; for all are ready to admit that without our political rights, our condition is very little better than it was before.

We have been looked upon with contempt, and despised without any cause, and if we are to be left without out the protection or [of] law, our condition will be awful, for wicked men will feel that they will have the right to abuse us of all occasions, and we not the slightest right in law to defend ourselves. All must know that it will a be great encouragement to commit crimes of injustice on us as a defeceless people and it will have a demoralizing effect on your own people. Now, we ask you to grant us this right, and we will be no trouble to you. We will take care of our own paupers, and we will, as we are now doing, help fight your battles in the field, and let us help you fight the rebels at the ballot-box, and that will be no disgrace to the State. We are not asking social equality; it is political rights, and it is no more than what you granted to the free colored men of the State years ago, facts you all know; many of our fathers voted for men that still live in this State; and they did not think it any disgrace then, and it had no bad influence then, and how could it now in these days of revolution?

As to our loyalty, it is settled beyond all contradiction. Wherever you meet a colored man you find in him a warm and devoted friend of the United States Government.

We ask in all humility, what has the colored man done that he should be denied these rights? He has been an obedient servant for two hundred years, and has obeyed the white man in all things.

All are ready to say it would be justice, and would have good results on society generally; for just at this time it would have a good influence on these much abused people in fitting them for society, for if we have no law to protect us, we will not be encouraged to make anything, or have property; but if we can have an assurance that we will be protected, it will make us industrious and persevering in obtaining means as other men, which will have good effect on the country, now and throughout all time.

We know we have been mistreated, and the world knows it; but we have no charge against you, for the whole matter gives as [us?] our political rights, and we are your everlasting friends, and you can rely upon as in every case where our aid is needed; then politically whatever is your interest will be ours, then will we have peace throughout the entire State; for we intend to whip the rebels into peace.

We do not wish for Tennessee to be behind; you see what other States are doing, and we don’t want it said of Tennessee — one of the most loyal States in the Union — to refuse to grant what other States give their colored people without asking for it. We feel confident we will obtain it, but we do desire that you give us the right, for you have done such a noble act in abolishing slavery in this State you deserve much credit for such a glorious act.

Now we ask you to give this matter a candid consideration, and when you have done that we have no fears but you will nobly respond to the call. You cannot help seeing, under our limited privileges, we have made some progress, and if we can have any show in law, we will do more to better the country generally. We claim, that by birth, this is our country, and you will find us as willing to make sacrifices as any other people. We contend we have not had a chance yet: Give us a chance and then if we do not prove to the world what we have promised, then we deserve to be branded; but not until then.

It will be said we will want to rank ourselves with the white people; not so; we ask you to pass a law, forever deb[???]ring a marriage between the two races, throughout all time.

Feeling we are addressing the most intelligent and humane body that has ever met in the Capitol of the State, we feel it unnecessary to say more. Hoping to be kindly remembered by you in your deliberations, we assure you that you and your interest and the interest of the whole state will be ever uppermost.

In our oppressed minds, we beg to subscribe ourselves your humble petitioners, calling on you to give us justice.

Mr. SMITH moved to refer it to the Committee on Freedmen, which was concurred in.

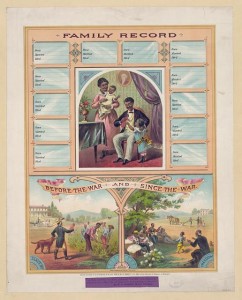

Read about the family record contrasting slavery and freedom at the Library of Congress

- [1]Fredriksen, John C. Civil War Almanac. New York: Checkmark Books, 2008. Print. page 557.↩