From the Seneca County Courier July 13, 1865:

LETTER FROM A SENECA FALLS SOLDIER-BOY.

The following interesting letter is from a native of this town, who was among the very first to respond to the President’s first call for Volunteers and who continued in the army during the war:

CAMP 1st N.Y. (LINCOLN) CAVALRY,

HART’S ISLAND, N.Y. HARBOR,

Friday, July 7th, 1865.

FRIEND FULLER – Today our regiment, with others has been discharged from the military service of the United States. Four years ago, with hundreds of thousands more, we marched southward to aid in restoring the authority of the Union. We followed McClellan through his Peninsula campaigns and through his subsequent campaign in Maryland. Transferred to the Department of West Virginia shortly after the battle of Antietam, we saw arduous service among the Alleghany Mountains and in the Valley of Virginia until Milroy’s retreat from Winchester in June 1863. After participating in the second campaign north of the Potomac, we returned to our rich “hunting grounds” in the Shenandoah Valley, where the tracks of our scouting parties would make a complete net work stretching from the Potomac to Harrisonburg; and from the South Branch, beyond the Blue Ridge. In January, 1864, we re-enlisted for three years or during the war. Returning from veteran furlough, we fought with Sigel at New Market, and followed Hunter on his raid to Lynchburg, and on that long weary retreat across the mountains to the Ohio River. – Returning to the Valley by railway, we went through Sheridan’s active campaign, under the immediate command of the gallant Averill. Breaking camp on the morning of Feb. 27th, the regiment now in Custer’s division, followed Sheridan until Lee and Johnston had surrendered. Ordered back to Alexandria and thence here, we are again to-night civilians, and proud citizens of the grandest nation on earth.

To-night we look on a picture of peace. – Near the long rows of the white tents of our camp, now almost deserted, the waters of the old salt sea ripple gently along the shore. – Ships and schooners are slowly sailing past where the full moon shines down on the harbor and the opening sound. There are no more details for guard or picket duty during the long night. No more fear of bugles sounding “boots and saddles” to call us hurriedly at midnight from our hard beds. No more expectation of going into battle in the morning. No more bivouacs on the frozen ground, holding our horses by the bridles as we sleep. It is hard to realize the change as we recall some of the stirring times through which we have passed, when a day without fight was something unusual. We recall the “Seven days” before Richmond, and the long weary days on Hunter’s raid, where, with nothing to eat, we would ride all day, and lie down supperless at midnight to dream of splendid dinners at our homes in the North; awaking to breakfast on birch bark and a handful of corn, and resume our march over the interminable mountains. Faint as we were, how we found strength to cheer the wagon train, with its precious load of “hard tack,” that at last met us.

We remember the dark days of doubt when we would wonder if all these things were to be, after all, in vain. We have always had a kind of respect for bold-fighting rebels, but words are wanting to tell what we have thought, and still think of the faint-hearted or malicious traitors in the North; old men finding fault with the Administration and Gen. Grant, and worrying about the price of gold; young men fleeing to Canada, or bravely submitting to any sacrifices, even the mutilation of their own bodies, that they might not be subject to the draft; women, who never sewed a stitch nor spoke a word of encouragement for the suffering soldiers. On that memorable Sunday after the fall of Sumter, a venerable man of God taught the religious duty of patriotism. said he, “If there be in this church any man or woman who will not, with all their energies, support the cause of our country in this hour of her peril, let them not enter my house nor touch my hand.”

It is with different feelings that we remember those who have worked so constantly for the soldiers; who have supplied them with necessaries and luxuries; who have written and spoken so many kind words of encouragement, friendship and Christian hope. The remembrance of their good deeds will be a source of happiness to them always.

We have many sorrowful recollections of brave, generous comrades whom we have left buried in Southern soil; either killed in battle or starved in prisons. But it some consolation to know that they do not rest in a foreign land.

We believe that the sacrifices it has cost to preserve the Union will teach the people vigilance in the future. None of us can ever forget our sorrow for the martyred Lincoln, nor what we owe to the true patriot Generals and statesmen who have led the country through its past perils.

Yours, &c., ***

The New York State Military Museum explains that the standard pictured up top was used after the initial three year enlistment had been served.

The Library of Congress provides the 1862 map of the Shenandoah Valley by Jedediah Hotchkiss. A few days ago I noticed that a 1945 dictionary did not have an entry for network

___________________________________________________________

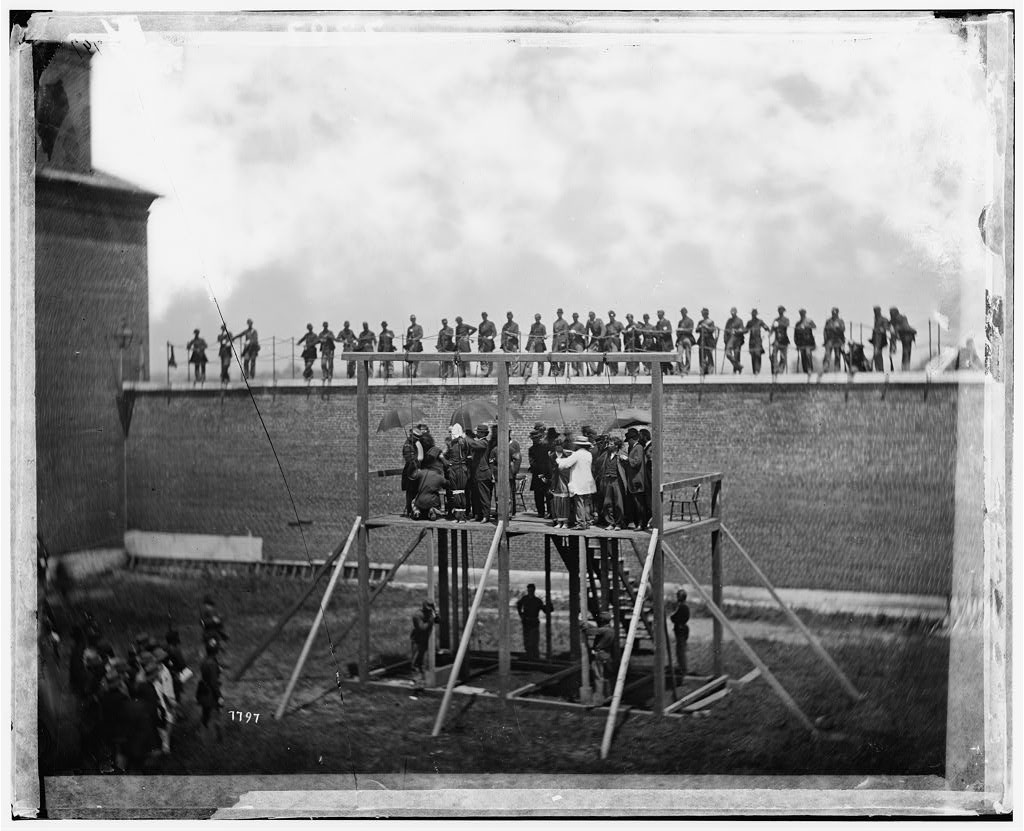

Less than three months after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln four convicted conspirators were hanged: