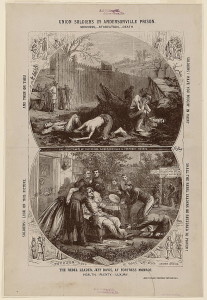

“Union soldiers in Andersonville prison / The rebel leader, Jeff Davis, at Fortress Monroe / Th. Nast. ” (Library of Congress)

From The New-York Times August 25, 1865:

WASHINGTON NEWS.; Return of the Andersonville Burial Party. Their Report Upon the Condition of that Earthly Hell. The Graves of Thirteen Thousand Martyrs Identified. Monuments Erected and the Cemetery Put in Order. The Old Prison Pen Carefully Preserved as the Rebels Left It. OUR DEAD AT ANDERSONVILLE. A VISIT TO RICHMOND. ABOUT GEN. BUTLER’S RESIGNATION. FROM WASHINGTON. A RUFFLAN FOILED. DISFRANCISED. A HERO COMING. COLORED TROOPS. SOUTHERN MAILS.

WASHINGTON, Thursday, Aug. 24.

As a fit commentary on the trial of the Andersonville prison-keeper now taking place in this city, Capt. JAMES M. MOORE, Assistant Quartermaster, and party to-day returned from Andersonville, where they have been engaged for the past month in identifying the graves and giving honored sepulture to the fourteen thousand victims of rebel barbarity who suffered all manner of torture and death in that notorious prison-pen. Capt. MOORE and party, consisting of clerks, painters, letterers, carpenters, &c., to the number of forty-two, including Miss CLARA BARTON, left here on the 8th of July, and proceeded to Andersonville by way of Savannah, up the river by steamer to Augusta, thence by rail to Atlanta, Macon and Andersonville. The railroad between Augusta and Atlanta is the only one of the routes destroyed by SHERMAN in his march across Georgia, that is yet in operation. The Georgia Central road from Savannah to Macon is yet a wreck in many places, and will not be repaired for months to come. At Macon Gen. WILSON, who took a deep interest in Capt. MOORE’s work, detailed a small force to assist him, and on the 26th of July the party began their labors. The dead were found buried in trenches on a site selected by the rebels about 300 yards from the stockade. The trenches were from three to four feet deep, and in a clayey soil. It is rather remarkable that it is the only clay soil in nll that vicinity, and it is, therefore, inferred that the rebels selected it to prevent the exhumation of bodies by the action of the elements, thereby adding to the effluvia from the vicinity, which the people for miles around in that section loudly complained of.

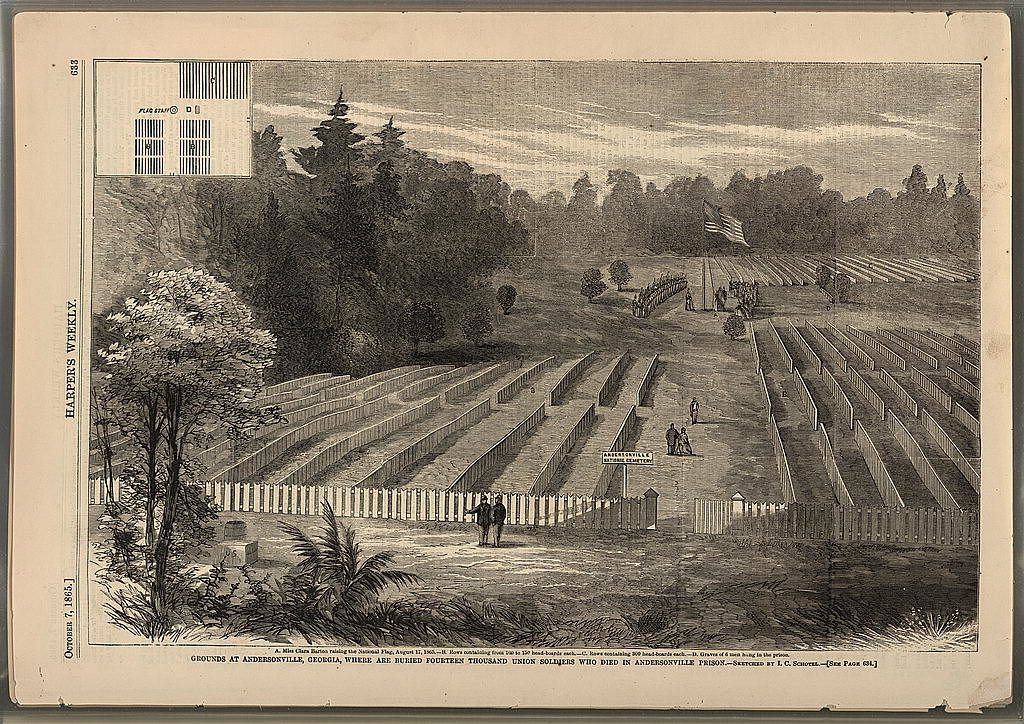

By means of a stake at the head of each grave, which bore a number corresponding with a similar numbered name upon the Andersonville Hospital records, most fortunately captured by Gen. WILSON last Spring, Capt. MOORE rejoices to say that he was enabled to identify, mark and honor the graves of thirteen thousand of the dead. To all but 500 of those buried in that vast cemetery, a neat tablet, about two feet I high, painted white, and lettered in black with the number, name, company and regiment of each, was placed at the head of each grave.

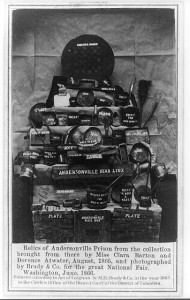

“Relics of Andersonville Prison from the collection brought from there by Miss Clara Barton and Dorence Atwater, August, 1865, and photographed by Brady & Co. for the great National Fair, Washington, June, 1866. ” (Library of Congress)

Nearly eighty thousand feet of pine lumber were used in these tablets alone. The cemetery has been divided by one main avenue running through the centre, and subdivided into blocks and sections in such a manner that with the aid of the numbers a visitor can go to any particular grave without difficulty. A force of men is now engaged in laying out walks, clearing the cemetery of stumps, stones, &c., and will this Fall beautify by setting out trees, &c. A neat board fence incloses the entire area, about 50 acres, and a flagstaff in the centre, with colors at half-mast, marks the honored “city of the dead.” In a circle on a large board over the gate are the words, “National Cemetery, Andersonville.” In the grounds at various places Capt. MOORE caused appropriate inscriptions to be placed, and endeavored, so far as his facilities would permit, to do whatever was possible to transform the wild, unmarked, unhonored graveyard into a fit place of entombment for the nation’s gallant dead. Capt. MOORE found the prison, pen in a perfect state of preservation, just as the rebels left it, buildings, stockade and ground huts, and the veritable dead-line as palpable as ever. That the controversy about the existence of this line may be settled, Capt. MOORE brought a piece of it away with him. One of the first things Gen. WILSON did after the capture of Macon, was to send a force to Andersonville, take possession of and preserve everything about the place. Nothing has been destroyed, and as, our exhausted, emaciated and enfeebled soldiers left it, so it stands to-day, a monument to an inhumanity unparalleled in the annals of war Andersonville itself consists of but one solitary house aside from the buildings erected by the rebels for their use.

The people who live in that locality assert that it is notorious for its unhealthinese; that it is known to be the most unhealthy part of Georgia. Malarious fevers constantly prevail, and one of Capt. MOORE’s party, a, young man named EDWARD WATTS, fell a victim to typhoid fever just before the party left. Two soldiers of the force, detailed by Gen. WILSON, also died, and one was murdered by a guerrilla. At a station named Montezuma, just outside the stockade, stands pine timber enough to build hundreds of miles of log huts, had our prisoners been allowed to use it. Near the inclosure is also the veritable dog kennels where were kept the leash of bloodhounds which the rebel Col. GIBBS to-day testified, in the Wirz trial, were regularly mustered into the service, received regular rations, and were used for recapturing escaped fugitives. While Capt. MOORE and party were engaged in their work they were obliged to camp out in regular army style, the accommodations of Andersonville consisting of but one house. The people of that vicinity are a lazy, sallow-faced, haggard, ignorant class. Their ignorance was especially astonishing. One man was found who had not heard of President LINCOLN’s death, and another who refused greenbacks because his government would not allow him to take those things. He absolutely did not know that the Southern Confederacy had gone up. At present Andersonville is guarded by a small force from Macon. A superintendent of the grounds and buildings was appointed by Capt. MOORE, and everything pertaining to the place will be carefully preserved. A list of the dead was brought back, and as soon as it can be prepared it will probably be published. It will be a vast and solemn “Roll of Honor.” Miss CLARA BARTON, who accompanied the party, has also returned. She took a deep interest in the noble work, submitted cheerfully to all the sacrifices and privations, and rendered very efficient aid. The entire party deserve the thanks of the country for their services. …

James Miles Moore helped develop Arlington National Cemetery, where he was eventually buried.

The trial of Andersonville commandant Henry Wirz did indeed make several front pages of The New-York Times 150 years ago this month.

The struggle to complete a more durable Transatlantic telegraph cable was also front page news that August. Those headlines brought back memories of one of my most enduring images of the Civil War’s 150th – the steam-tug in the cold March waters off Newfoundland trying to intercept the next ship for Europe with the telegraphed synopsis of President Lincoln’s first inaugural address