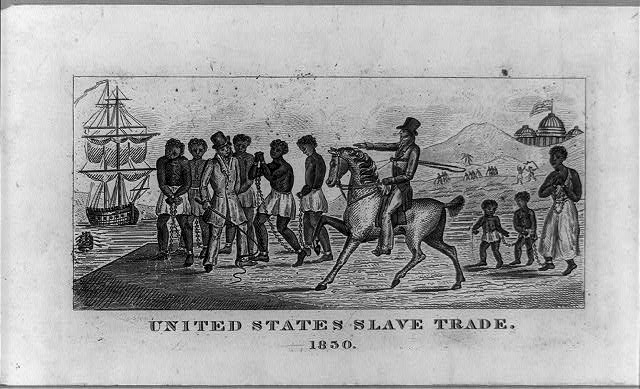

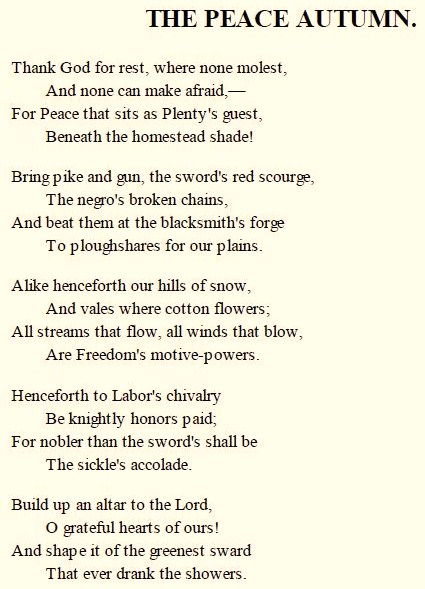

A poem from 150 years ago celebrated peace and the victory of freedom and free labor over slavery:

From The Atlantic Monthly, VOL. XVI.—NOVEMBER, 1865.—NO. XCVII.

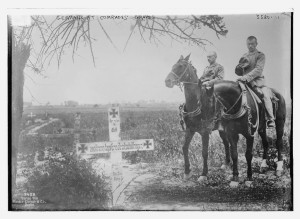

“Who died to make the slave a man” (“Richmond, Virginia (vicinity). Soldiers graves ” Library of Congress)

___________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________

Our modern Veteran’s Day springs from Armistice Day: The shooting finally stopped in World War I on November 11, 1918 – at 11:00 AM Paris Time.

Here’s a bit about that day with an American slant. From History of the World War An Authentic Narrative of the World’s Greatest War, by Francis A. March and Richard J. Beamish (1919) (in Chapter LII):

The last action of the war for the Americans followed immediately on the heels of the battle of Sedan. It was the taking of the town of Stenay. The engagement was deliberately planned by the Americans as a sort of battle celebration of the end of the war. The order fixing eleven o’clock as the time for the conclusion of hostilities, had been sent from end to end of the American lines. Its text follows:

1. You are informed that hostilities will cease along the whole front at 11 o’clock A. M., November 11, 1918, Paris time.

2. No Allied troops will pass the line reached by them at that hour in date until further orders.

3. Division commanders will immediately sketch the location of their line. This sketch will be returned to headquarters by the courier bearing these orders.

4. All communication with the enemy, both before and after the termination of hostilities, is absolutely forbidden. In case of violation of this order severest disciplinary measures will be immediately taken. Any officer offending will be sent to headquarters under guard.

5. Every emphasis will be laid on the fact that the arrangement is an armistice only and not a peace.

6. There must not be the slightest relaxation of vigilance. Troops must be prepared at any moment for further operations.

7. Special steps will be taken by all commanders to insure strictest discipline and that all troops be held in readiness fully prepared for any eventuality.

8. Division and brigade commanders will personally communicate these orders to all organizations.

Signal corps wires, telephones and runners were used in carrying the orders and so well did the big machine work that even patrol commanders had received the orders well in advance of the hour. Apparently the Germans also had been equally diligent in getting the orders to the front line. Notwithstanding the hard fighting they did Sunday to hold back the Americans, the Germans were able to bring the firing to an abrupt end at the scheduled hour.

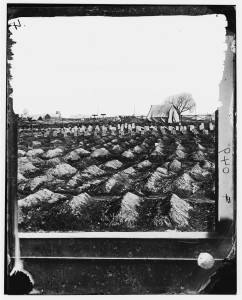

“a British soldier tending a soldier’s grave near Blangy, May 3, 1917 during the Battle of Arras, a French city on the Western Front, during World War I.” (Library of Congress)

The staff and field officers of the American army were disposed early in the day to approach the hour of eleven with lessened activity. The day began with less firing and doubtless the fighting would have ended according to plan, had there not been a sharp resumption on the part of German batteries. The Americans looked upon this as wantonly useless. It was then that orders were sent to the battery commanders for increased fire. …

The early forenoon had been marked by a falling off in fire all along the line, but an increasing bombardment from the retreating Germans at certain points stimulated the Americans to a quick retort. From their positions north of Stenay to southeast of the town the Americans began to bombard fixed targets. The firing reached a volume at times almost equivalent to a barrage.

Two minutes before eleven o’clock the firing dwindled, the last shells shrieking over No Man’s Land precisely on time.

There was little celebration on the front line, where American routine was scarcely disturbed over the cessation of fighting. In the areas behind the battle zone there were celebrations on all sides. Here and there there were little outbursts of cheering, but even those instances were not on the immediate front.

Many of the French soldiers went about singing.

“Well, I don’t know,” drawled a lieutenant from Texas while the artillery was sending its last challenge to the Germans, “but somehow I can’t help wondering if we have licked them enough.” …