As Walter Stahr explains in his biography of William H. Seward, after the American Civil War ended, famous Union generals were eager to invade Mexico and drive the French and Maximilian I out of North America. Ulysses S. Grant “was keen to enforce the Monroe doctrine in Mexico,” by supporting the U.S. recognized Benito Juárez government. In July 1865 President Johnson read a letter from General Philip Sheridan to Grant stating that he and his troops were eager to cross the Rio Grande and march towards Mexico City.

Despite having been nearly killed in mid-April, Secretary Seward worked hard during the rest of 1865 to prevent a second Mexican war. He based his approach on his doubt that “invaders from the United States would be more welcome in Mexico than the French”. He argued at cabinet meetings that the French would eventually leave Mexico of their own volition and that, if the United States did drive out the French, “‘we could not get out ourselves.'” The Secretary of State co-opted General John Schofield, whom Grant intended to lead a joint American-Mexican army, by sending him to Paris. Mr. Seward limited the Juárez government ambassador’s access to President Johnson and assured General Grant that he was going to get the French out of Mexico with diplomacy. But he also used the threat of an invasion in his negotiations with the French. By the end of 1865 “Seward had not solved the Mexican crisis, but he had prevented Grant from leading the United States into a second Mexican war, and he had increased the pressure on France to get out of Mexico.” [1]

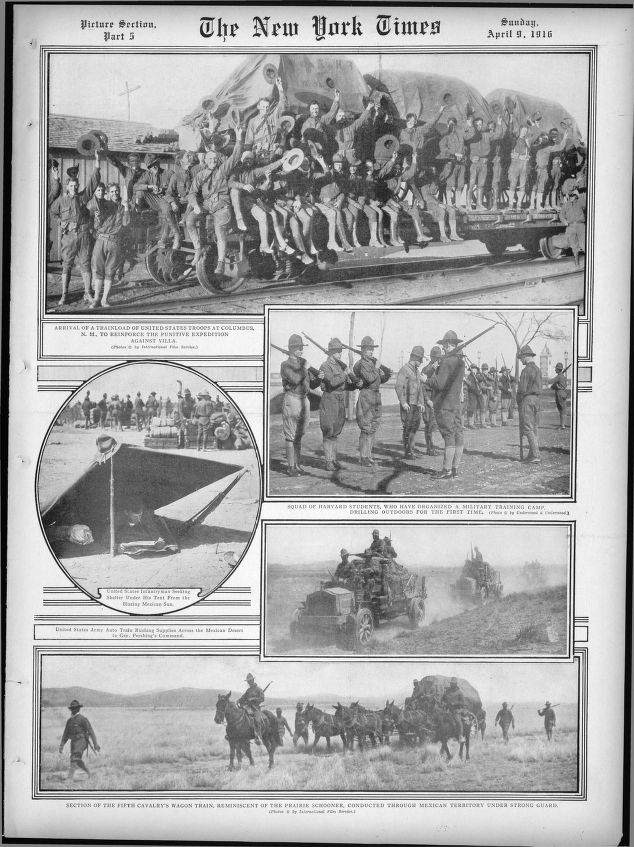

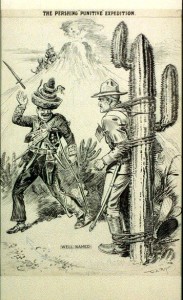

100 years ago this week another (at least soon to be) famous American general did invade Mexico in pursuit of a Mexican force commanded by Pancho Villa. John J. Pershing led the Pancho Villa Expedition, which:

was launched in retaliation for Villa’s attack on the town of Columbus, New Mexico, and was the most remembered event of the Border War. The declared objective of the expedition by the Wilson administration was the capture of Villa. Despite successfully locating and defeating the main body of Villa’s command, responsible for the raid on Columbus, U.S. forces were unable to prevent Villa’s escape and so the main objective of the U.S. incursion was not achieved.

Here’s a little more detail, from The Story of General Pershing by Everett Titsworth Tomlinson:

In Pursuit of Villa

General Pershing had been sent to the Mexican border in command of the Southwestern Division early in 1915. In command of the El Paso patrol district, he necessarily was busy much of his time in guarding and patrolling the long thin lines of our men on duty there.

The troubles with Mexico had been steadily increasing in seriousness. The rivalry and warfare between various leaders in that country had not only brought their own country into a condition of distress, but also had threatened to involve the United States as well. Citizens of the latter country had invested large sums in mining, lumber and other industries in Mexico and were complaining bitterly of the failure of our Government either to protect them or their investments. Again and again, under threats of closing their mines or confiscating their property, they had “bought bonds” of the rival Mexican parties, which was only another name for blackmail.

Raids were becoming increasingly prevalent near the border and already Americans were reported to have been slain by these irresponsible bandits who were loyal only to their leaders and not always to them. The condition was becoming intolerable.

Germany, too, had her agents busy within the borders of Mexico, artfully striving not only to increase her own power in the rich and distracted country, but also to create and foment an unreasonable anger against the United States, vainly hoping in this way to prevent the latter country from entering the World War by compelling her to face these threatening attacks from her neighbor on the south. President Wilson was doing his utmost to hold a steady course through the midst of these perils, which daily were becoming more threatening and perplexing.

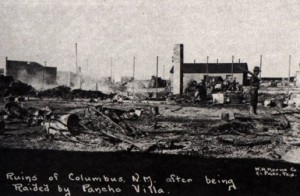

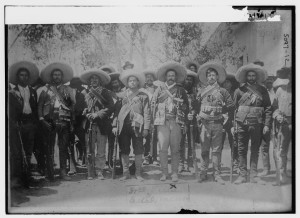

The climax came early in March, 191[6], when Francesco Villa, the most daring and reckless leader of all the Mexican bandit bands, suddenly with his followers made an attack on the post at Columbus, New Mexico. The American soldiers were taken completely by surprise. Their machine guns (some said there was only one at the post) jammed and their defense was inadequate. They were not prepared. When Villa withdrew he left nine dead civilians and eight dead American soldiers behind him.

Instantly the President decided that the time had come when he must act. There was still the same strong desire to avoid war with Mexico if possible. The same suspicion of Germany was in his mind, but in spite of these things Villa must be punished and Americans must be protected. Quickly a call for regulars and State troops was made and General Pershing was selected as the leader of the punitive expedition.

The New York Sun, in an editorial at the time of his selection, said: “At home in the desert country, familiar with the rules of savage warfare, a regular of regulars, sound in judgment as in physique, a born cavalryman, John J. Pershing is an ideal commander for the pursuit into Mexico.”

The selection indeed may have been “ideal,” but the conditions confronting the commander were far from sharing in that ideal. Equipment was lacking, many of his men, though they were brave, were untrained, and, most perplexing of all, was the exact relation of Mexico to the United States. There could not be said to exist a state of war and yet no one could say the two countries were at peace. He was invading a hostile country which was not an enemy, for the raids of bandit bands across the border did not mean that Mexico as a state was attacking the United States. He must move swiftly across deserts and through mountain fastnesses, he was denied the use of railroads for transporting either troops or supplies, enemies were on all sides who were familiar with every foot of the region and eager to lure him and his army into traps from which escape would be well nigh impossible. The fact is[122] that for nearly eleven months Pershing maintained his line, extending nearly four hundred miles from his base of supplies, in a country which even if it was not at war was at least hostile. It is not therefore surprising that after his return the State of New Mexico voted a handsome gold medal to the leader of the punitive expedition for his success in an exceedingly difficult task.

It was on the morning of March 15, 1916, when General Pershing dashed across the border in command of ten thousand United States cavalrymen, with orders to “get” Villa. A captain in the Civil War who was in the Battle of Gettysburg, when he learned of the swift advance of General Pershing’s forces, said: “The hardest march we ever made was the advance from Frederick. We made thirty miles that day between six o’clock a.m. and eleven o’clock p.m. But Maryland and Pennsylvania are not an alkali desert. I have an idea that twenty-six miles a day, the ground Pershing was covering on that waterless tramp in Mexico, was some hiking.” And the advance[123] is one of the marvels of military achievements when it is recalled that the march was begun before either men or supplies, to say nothing of equipment, were in readiness. …

Although the punitive expedition failed in its main purpose,—the capture of Villa,—the opinion in America was unanimous that the leadership had been superb. The American Review of Reviews declared that “the expedition was conducted from first to last in a way that reflected credit on American arms.”

An interesting incident in this chapter of Pershing’s story is that fourteen of the nineteen Apache Indian scouts whom he had helped to capture in the pursuit of Geronimo, in 1886, were aiding him in the pursuit of Villa. Several of these scouts were past seventy years of age; indeed, one was more than eighty, but their keenness on the trail and their long experience made their assistance of great value. One of the best was Sharley and another was Peaches. Several of these Indian scouts are with the colors in France, still with Pershing. …

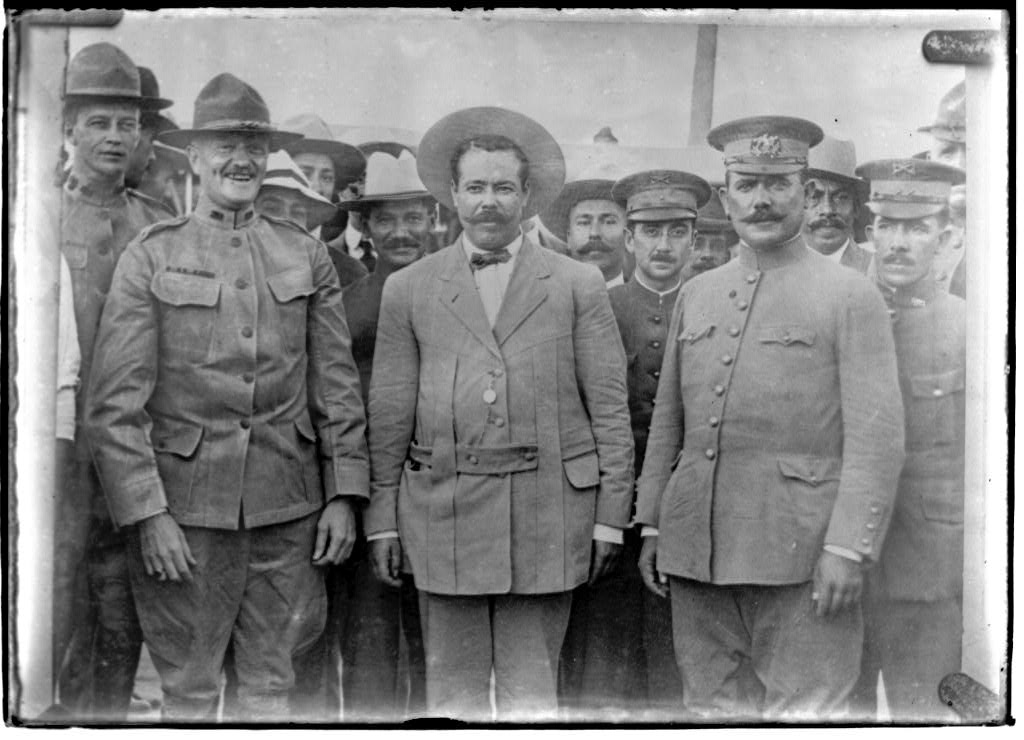

“U.S. Army Punitive Expedition after Villa, Mexico: General Pershing and General Bliss inspecting the camp, with Colonel Winn, Commander of the 24th Infantry” (Library of Congress)

_______________________________________________________

Another Wikisummary:

Villa subsequently led a raid against the U.S.-Mexican border town of Columbus, New Mexico in 1916. The U.S. government sent U.S. Army General John J. Pershing to capture Villa in an unsuccessful nine-month incursion into Mexican sovereign territory that ended when the United States entered World War I and Pershing was called back.

The Library of Congress provides the images of Richmond March, cactus cartoon, Black Jack inspecting, Pancho and staff (“X” marks Villa’s spot), NY Times photo page. The Library also links to the photo of Pershing and Villa standing together. The man to the right of Villa is Álvaro Obregón; the soldier to the left of Pershing might be George S. Patton. The barbed wire cartoon can be found at the National Archives.

- [1]Stahr, Walter Seward: Lincoln’s Indispensable Man. 2012. New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2013. Print. pages 440-446.↩

![Untitled. [I've Had About Enough of This] (https://catalog.archives.gov/id/306154)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/canvas.png)