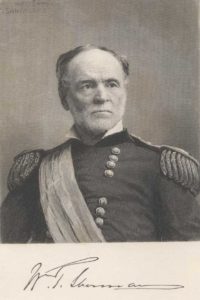

So far I haven’t noticed a letter from General William T. Sherman endorsing President Andrew Johnson’s reconstruction policy being published just before the 1866 elections in New York for its bombshell affect, but according to reports the general openly supported the president while he was in Washington, D.C. in October. From a Seneca County, New York newspaper in November 1866:

LIUTENANT [sic] GENERAL SHERMAN while in Washington made no secret of his support of the President’s policy. On one occasion he said, “Soldiers have something else to do now besides fighting. We fought the rebels as long as there were any rebels to fight. What we have now to do is to secure the object for which we fought. We fought to restore the Union; let us now restore it.” He frequently expressed his surprise and indignation that the Southern states were deprived of the right of representation so long after the termination of the war. – N.Y. Commercial Advertiser.

According to his 1889 memoirs, General Sherman had been in Washington at the request of Andrew Johnson. From The Memoirs of General W. T. Sherman, Second Edition, Volume II, in Chapter 26:

While these great changes were being wrought at the West, in the East politics had resumed full sway, and all the methods of anti-war times had been renewed. President Johnson had differed with his party as to the best method of reconstructing the State governments of the South, which had been destroyed and impoverished by the war, and the press began to agitate the question of the next President. Of course, all Union men naturally turned to General Grant, and the result was jealousy of him by the personal friends of President Johnson and some of his cabinet. Mr. Johnson always seemed very patriotic and friendly, and I believed him honest and sincere in his declared purpose to follow strictly the Constitution of the United States in restoring the Southern States to their normal place in the Union; but the same cordial friendship subsisted between General Grant and myself, which was the outgrowth of personal relations dating back to 1839. So I resolved to keep out of this conflict. In September, 1866, I was in the mountains of New Mexico, when a message reached me that I was wanted at Washington. I had with me a couple of officers and half a dozen soldiers as escort, and traveled down the Arkansas, through the Kiowas, Comanches, Cheyennes, and Arapahoes, all more or less disaffected, but reached St. Louis in safety, and proceeded to Washington, where I reported to General Grant.

He explained to me that President Johnson wanted to see me. He did not know the why or wherefore, but supposed it had some connection with an order he (General Grant) had received to escort the newly appointed Minister, Hon. Lew Campbell, of Ohio, to the court of Juarez, the President-elect of Mexico, which country was still in possession of the Emperor Maximilian, supported by a corps of French troops commanded by General Bazaine. General Grant denied the right of the President to order him on a diplomatic mission unattended by troops; said that he had thought the matter over, world disobey the order, and stand the consequences. He manifested much feeling; and said it was a plot to get rid of him. I then went to President Johnson, who treated me with great cordiality, and said that he was very glad I had come; that General Grant was about to go to Mexico on business of importance, and he wanted me at Washington to command the army in General Grant’s absence. I then informed him that General Grant would not go, and he seemed amazed; said that it was generally understood that General Grant construed the occupation of the territories of our neighbor, Mexico, by French troops, and the establishment of an empire therein, with an Austrian prince at its head, as hostile to republican America, and that the Administration had arranged with the French Government for the withdrawal of Bazaine’s troops, which would leave the country free for the President-elect Juarez to reoccupy the city of Mexico, etc., etc.; that Mr. Campbell had been accredited to Juarez, and the fact that he was accompanied by so distinguished a soldier as General Grant would emphasize the act of the United States. I simply reiterated that General Grant would not go, and that he, Mr. Johnson, could not afford to quarrel with him at that time. I further argued that General Grant was at the moment engaged on the most delicate and difficult task of reorganizing the army under the act of July 28, 1866; that if the real object was to put Mr. Campbell in official communication with President Juarez, supposed to be at El Paso or Monterey, either General Hancock, whose command embraced New Mexico, or General Sheridan, whose command included Texas, could fulfill the object perfectly; or, in the event of neither of these alternates proving satisfactory to the Secretary of State, that I could be easier spared than General Grant. “Certainly,” answered the President, “if you will go, that will answer perfectly.”

General Sherman and party left for Mexico on November 10th.

According to Garry Boulard [1]General Grant declined the Mexico assignment in an October 21st note to the president:

“I have most respectfully to beg to be excused from the duty proposed. It is a diplomatic service for which I am not fitted either by education or taste.”

No longer, just because the president asked, would Grant respond. Johnson was astonished. A wide and unbridgeable chasm between the General-in-Chief and President had finally become a reality.

- [1]Boulard, Garry The Swing Around the Circle: Andrew Johnson and the Train Ride that Destroyed a Presidency. Bloomington, Indiana: iUniverse, 2008. Print. page 158.↩