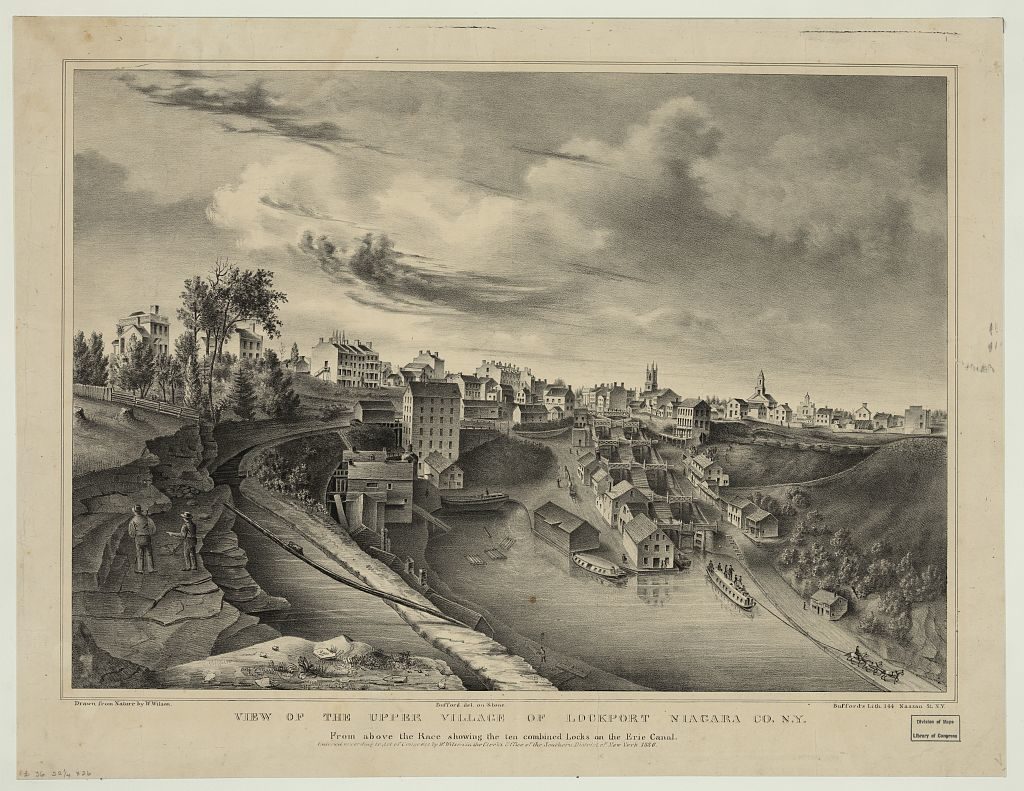

From a Seneca County, New York newspaper presumably sometime in 1866:

[pointing finger] A FEMALE CANAL DRIVER. – On Thursday last a canal driver was arrested in Lockport, on suspicion of being a woman in male attire. On being taken before a justice she owned up and was committed to jail, a fate not shared by all women who “wear the trousers.”

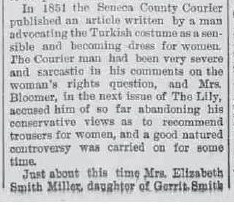

Seneca Falls, New York was a hotbed of the women’s rights movement and the dress reform that temporarily accompanied it. An obituary for Amelia Jenks Bloomer explained how her name became associated with the mid-19th century pantsuit (The Evening Dispatch (Provo, UT), February 7, 1895, Page 3, Image 3, col. 2-3.):

_______________

The obituary went on to say that Amelia Bloomer abandoned the costume after seven or eight years. Two possible reasons: she didn’t want to be known only for the dress reform, and she wanted to alleviate the social pressure applied to her husband.

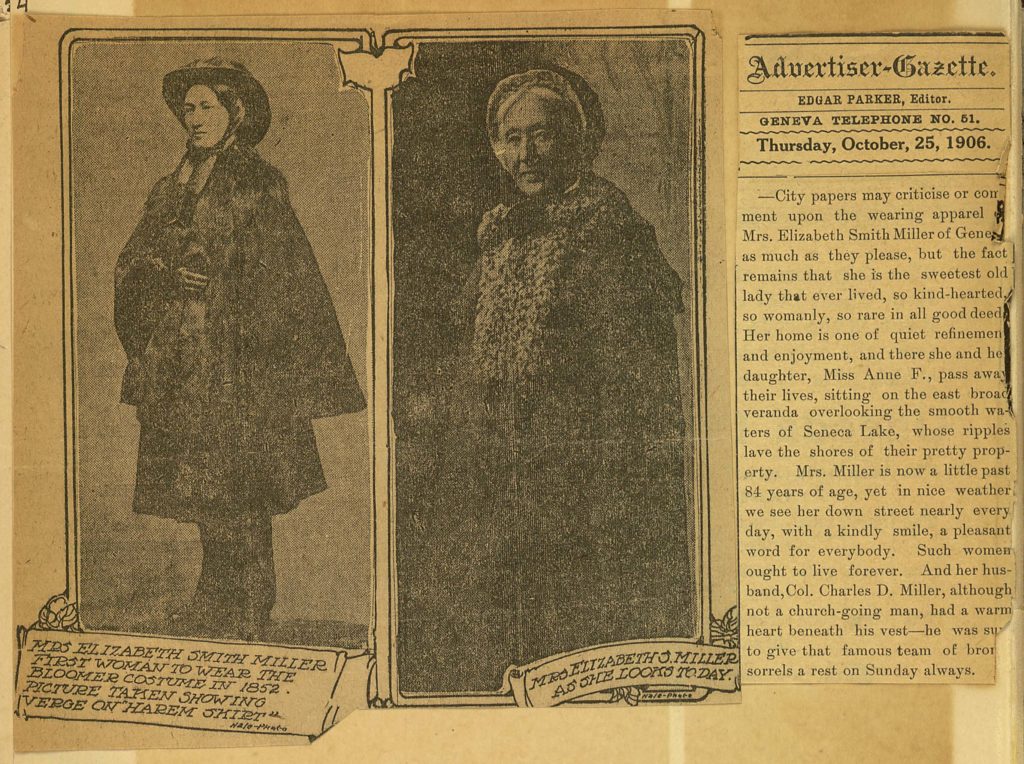

The National Park Service backs up the obituary’s claim that Elizabeth Smith Miller ” first wore the costume of Turkish pantaloons and knee length skirt popularized by Amelia Bloomer in The Lily. Reportedly, she began wearing the outfit after seeing this type of clothing on a trip to Europe.”

Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote about the new costume in History of Woman Suffrage, Volume II, edited by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage (1881; pages 469-471):

Quite an agitation occurred in 1852, on woman’s costume. In demanding a place in the world of work, the unfitness of her dress seemed to some, an insurmountable obstacle. How can you, it was said, ever compete with man for equal place and pay, with garments of such frail fabrics and so cumbrously fashioned, and how can you ever hope to enjoy the same health and vigor with man, so long as the waist is pressed into the smallest compass, pounds of clothing hung on the hips, the limbs cramped with skirts, and with high heels the whole woman thrown out of her true equilibrium. Wise men, physicians, and sensible women, made their appeals, year after year; physiologists lectured on the subject; the press commented, until it seemed as if there were a serious demand for some decided steps, in the direction of a rational costume for women. The most casual observer could see how many pleasures young girls were continually sacrificing to their dress: In walking, running, rowing, skating, dancing, going up and down stairs, climbing trees and fences, the airy fabrics and flowing skirts were a continual impediment and vexation. We can not estimate how large a share of the ill-health and temper among women is the result of the crippling, cribbing influence of her costume. Fathers, husbands, and brothers, all joined in protest against the small waist, and stiff distended petticoats, which were always themes for unbounded ridicule. But no sooner did a few brave conscientious women adopt the bifurcated costume, an imitation in part of the Turkish style, than the press at once turned its guns on “The Bloomer,” and the same fathers, husbands, and brothers, with streaming eyes and pathetic tones, conjured the women of their households to cling to the prevailing fashions. The object of those who donned the new attire, was primarily health and freedom; but as the daughter of Gerrit Smith introduced it just at the time of the early conventions, it was supposed to be an inherent element in the demand for political equality. As some of those who advocated the right of suffrage wore the dress, and had been identified with all the unpopular reforms, in the reports of our conventions, the press rung the changes on “strong-minded,” “Bloomer,” “free love,” “easy divorce,” “amalgamation.” I wore the dress two years and found it a great blessing. What a sense of liberty I felt, in running up and down stairs with my hands free to carry whatsoever I would, to trip through the rain or snow with no skirts to hold or brush, ready at any moment to climb a hill-top to see the sun go down, or the moon rise, with no ruffles or trails to be limped by the dew, or soiled by the grass. What an emancipation from little petty vexatious trammels and annoyances every hour of the day. Yet such is the tyranny of custom, that to escape constant observation, criticism, ridicule, persecution, mobs, one after another gladly went back to the old slavery and sacrificed freedom to repose. I have never wondered since that the Chinese women allow their daughters’ feet to be encased in iron shoes, nor that the Hindoo widows walk calmly to the funeral pyre. I suppose no act of my life ever gave my cousin, Gerrit Smith, such deep sorrow, as my abandonment of the “Bloomer costume.” He published an open letter to me on the subject, and when his daughter, Mrs. Miller, three years after, followed my example, he felt that women had so little courage and persistence, that for a time he almost despaired of the success of the suffrage movement; of such vital consequence in woman’s mental and physical development did he feel the dress to be.

Gerrit Smith Samuel J. May, J. C. Jackson, C. D. Miller and D. C. Bloomer, sustained the women who lead in this reform, unflinchingly, during the trying experiment. Let the names of those who made this protest be remembered. We knew the Bloomer costume never could be generally becoming, as it required a perfection of form, limbs, and feet, such as few possessed, and we who wore it also knew that it was not artistic. Though the martyrdom proved too much for us who had so many other measures to press on the public conscience, yet no experiment is lost, however evanescent, that rouses thought to the injurious consequences of the present style of dress, sacrificing to its absurdities so many of the most promising girls of this generation.

Amelia Bloomer published The Lily from 1849 to 1853. The paper initially focused on promoting temperance but later took on more women’s rights issues. Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote several articles for the paper “under the pseudonym ‘sunflower’.” You can read more about The Lily at Accessible Archives

_______________________________