The Battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg) on September 17, 1862 was the bloodiest single day of the American Civil War. 150 years ago today dignitaries dedicated a national cemetery at the battlefield and laid the cornerstone of a national monument. It was a big event. According to The New-York Times arrangements were made so that round-trip tickets on the Baltimore & Ohio to Sharpsburg for the dedication were reduced to two-thirds the regular price; many government officials, military officers, foreign dignitaries attended; Dr. Elisha Harris, who was in charge of distributing supplies from the United States Sanitary Commission to the seventy-one “surgical depots” on and near the field after the battle accepted an invitation; the Commissioners of the Antietam Monument accepted the design of James G. Batterson for the approximately $30,000 “colossal statue and pedestal.”

According to the main report in the Times about 8,000 people attended the ceremony (only 2,000 could hear the proceedings) (according to Historynet’s account almost 15,000 were present). Like the dedication at Gettysburg back in November 1863 the main oration was not given by the United States president (Maryland’s ex-governor Augustus Bradford played the Edward Everett role); however, similarly to Gettysburg, President Andrew Johnson did say a few words. Unlike Gettysburg, those words didn’t go down in history, although they were recorded for history. From The New-York Times September 18, 1867:

… MY FELLOW-COUNTRYMEN: In appearing before you it is not for the purpose of making any lengthy remarks, but simply to express my approbation of the ceremonies which have taken place to-day. My appearance on this occasion will be the speech that I will make; my reflections and my meditations will be in silent communion with the dead whose deeds we are here to commemorate. I shall not attempt to give utterance to the feelings and emotions inspired by the addresses and prayers which have been made, and the hymns which have been sung. I shall attempt no such thing. I am merely here to give my countenance and aid to the ceremonies on this occasion; but I must be permitted to express my hope that we may follow the example which has been so eloquently alluded to this afternoon, and which has been so clearly set by the illustrious dead. When we look on your battle field and think of the brave men on both sides who fell in the fierce struggle of battle, and who sleep silent in their graves, yes, who sleep in silence and peace after the earnest conflict has ceased, would to God we of the living could imitate their example as they lay living in peace in their tombs, and live together in friendship and peace. [Applause.] You, my fellow-citizens, have my earnest wishes, as you have had my efforts in times gone by, in the earliest and most trying perils to preserve the Union of these States, to restore peace and harmony to our distracted and divided country, and you shall have my last efforts in vindication of the flag of the Republic and of the Constitution of our fathers. [Applause.] …

The Times editorial on September 18th didn’t mention Andrew Johnson at all. It expressed the importance of honoring the (patriotic, Northern) war dead, but it was slightly critical of Governor Bradford’s oration for focusing too much on the facts of the Maryland campaign (although the Times began its main report with its own summary of invasion of 1862). The editorial ended with the “almost inspired language” of the ending of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address from “In a larger sense …” on.

I can’t tell from Andrew Johnson’s speech whether he realized that only Union soldiers were buried at Antietam. According to the National Park Service:

The original Cemetery Commission’s plan allowed for burial of soldiers from both sides. However, the rancor and bitterness over the recently completed conflict and the devastated South’s inability to raise funds to join in such a venture persuaded Maryland to recant. Consequently, only Union dead are interred here. Confederate remains were re-interred in Washington Confederate Cemetery in Hagerstown, Maryland; Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Frederick, Maryland; and Elmwood Cemetery in Shepherdstown, West Virginia. Approximately 2,800 Southerners are buried in these three cemeteries, over 60% of whom are unknown.

President Johnson might have rankled his audience by mentioning the “brave men on both sides.” His goal of peace, harmony, and friendship sound real good; back then that ideal was proving divisive – unlike the Congress, the president didn’t seem to care whether peace and harmony included anything like equal rights for the ex-slaves.

_________________________________________

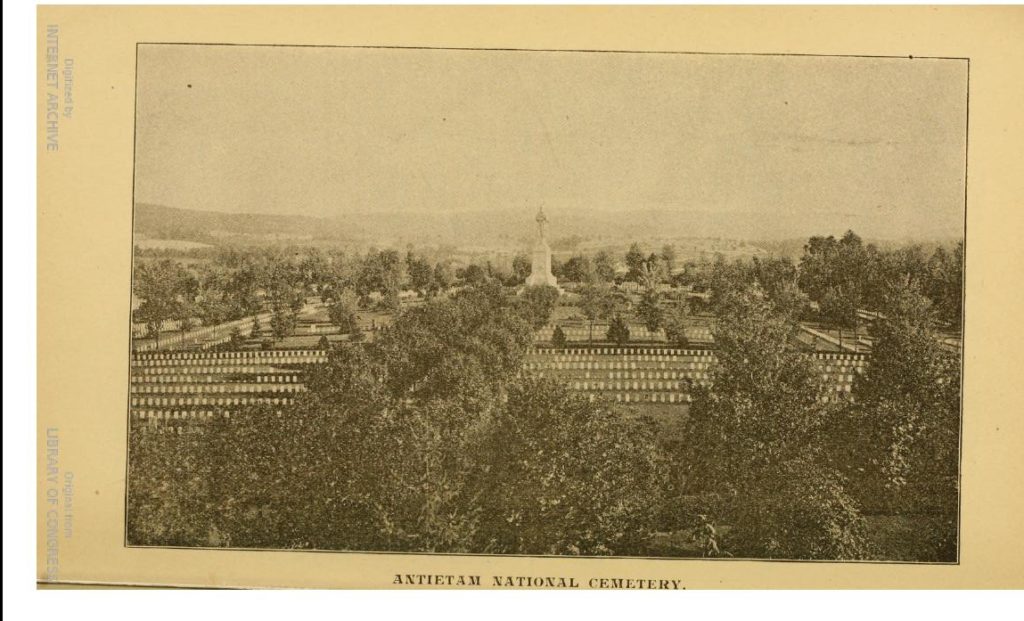

The image of Sharpsburg was published in 1869’s History of Antietam National Cemetery, including a descriptive list of all the loyal soldiers buried therein: together with the ceremonies and address on the occasion of the dedication of the grounds, September, 17th, 1867. (at HathiTrust), The same book reported a slightly different version of President Johnson’s remarks, including “yon battle field”, which might make more sense than “your battle field”. The 1890 photo of the cemetery and the image of Andrew Johnson’s speech comes from an updated version of the dedication ceremonies also at HathiTrust. The newer book also added President Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. Both books show that the Freemasons had a large part in the cemetery dedication. That must have pleased Andrew Johnson, who was a “proud brother,” who “took part in the ceremonies of the Washington Templars.” In June 1867 “he was inducted into the higher degrees of the order.”That same month the president traveled to Boston for the dedication of a new temple.[1]

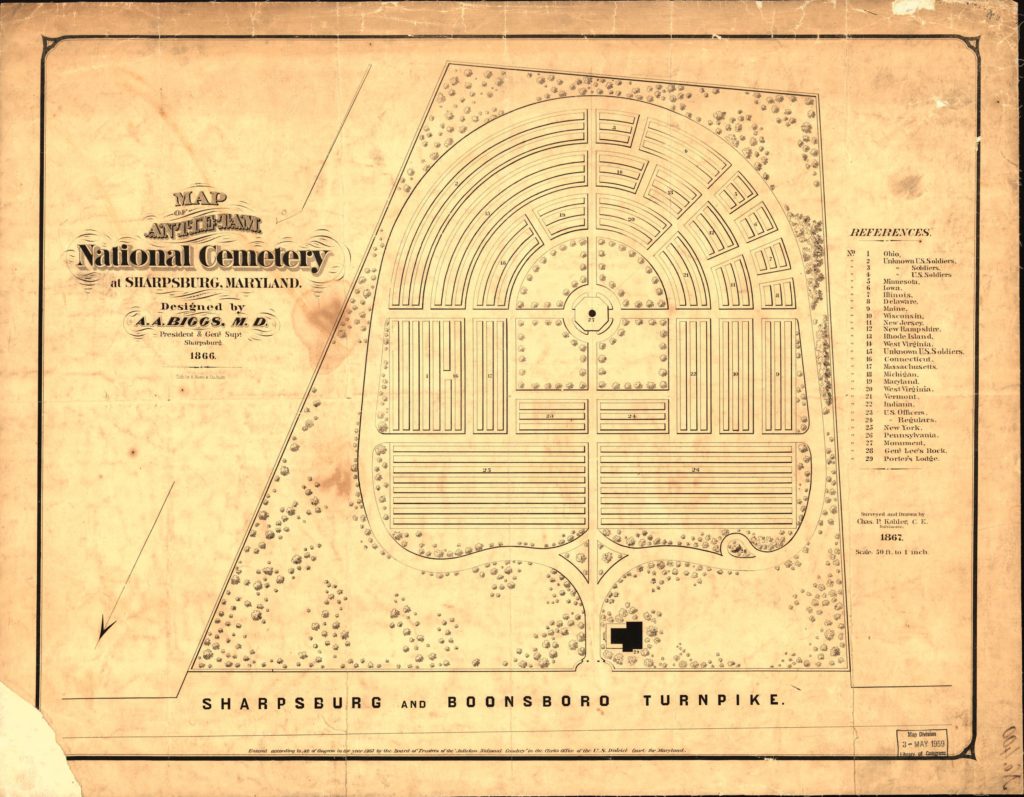

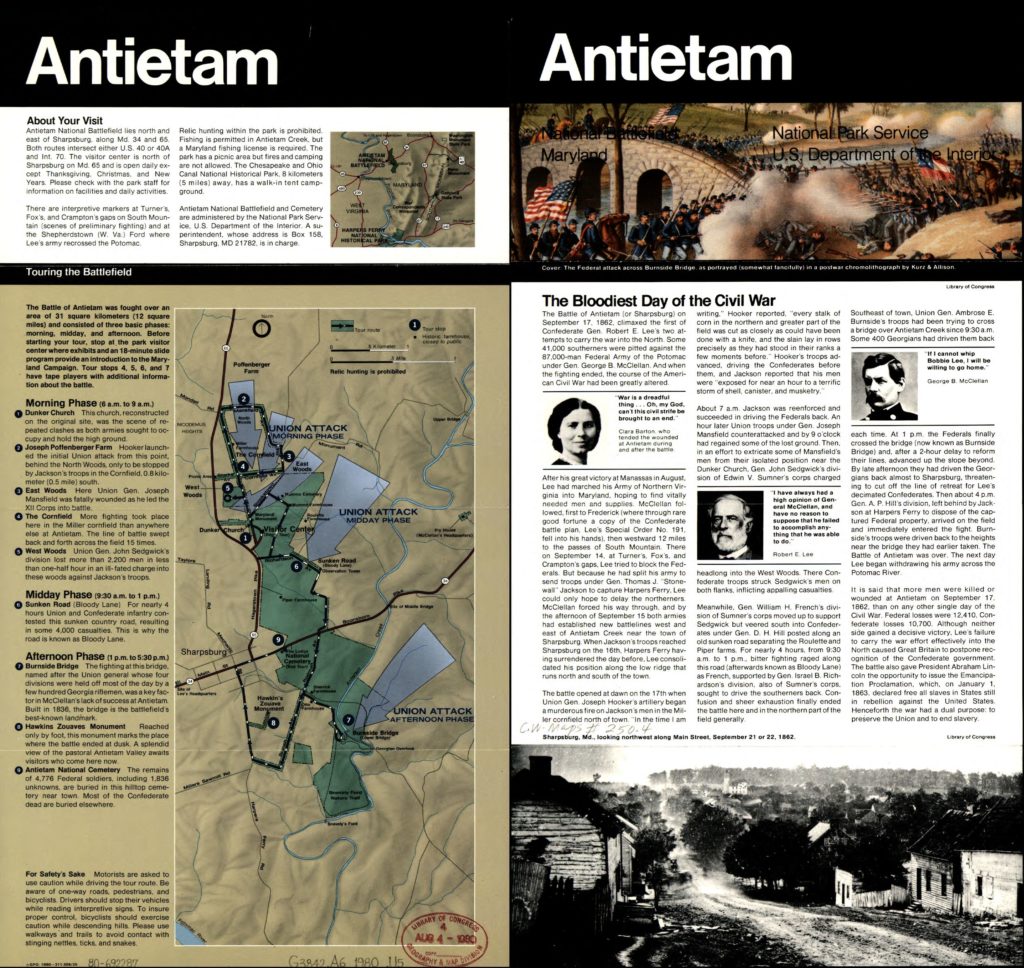

The cemetery map comes from the Library of Congress. You can read about the map’s mysterious No.28 – General Lee’s Rock at Crossroads of War. The issues involved with Lee’s Rock sound like today’s current events. The rock was gone by September 1868.

The Times in it’s “Sketch of the Battle” that began its main report included General Lee’s September 8, 1862 message to the people of Maryland and then commented: “… while Gen. LEE was thus proclaiming his pacific intentions, and giving exemplication of them by plundering everybody within reach of his troops …”

Also from the Library of Congress: Carol M. Highsmith’s photo of the private soldier monument, which made it to the cemetery in 1880. It spent time at Philadelphia’s centennial exposition; a nice Antietam review from the National Park Service

President Johnson’s remarks reminded me of Eric Foner’s comment on his 1866 Washington’s Birthday address: “… in a speech one hour long he referred to himself over 200 times …”[2] And as Hans L. Trefousse wrote (in the context of the “Swing Around the Circle”) “… the trouble with Johnson’s speeches was that he never fully prepared any of them in detail.[3]

- [1]Trefousse, Hans L. Andrew Johnson: A Biography. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1997. Print. pages 286.↩

- [2]Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877. New York: HarperPerennial, 2014. Updated Edition. Print. page 249.↩

- [3]Trefousse, Hans L. Andrew Johnson: A Biography. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1997. Print. pages 266.↩