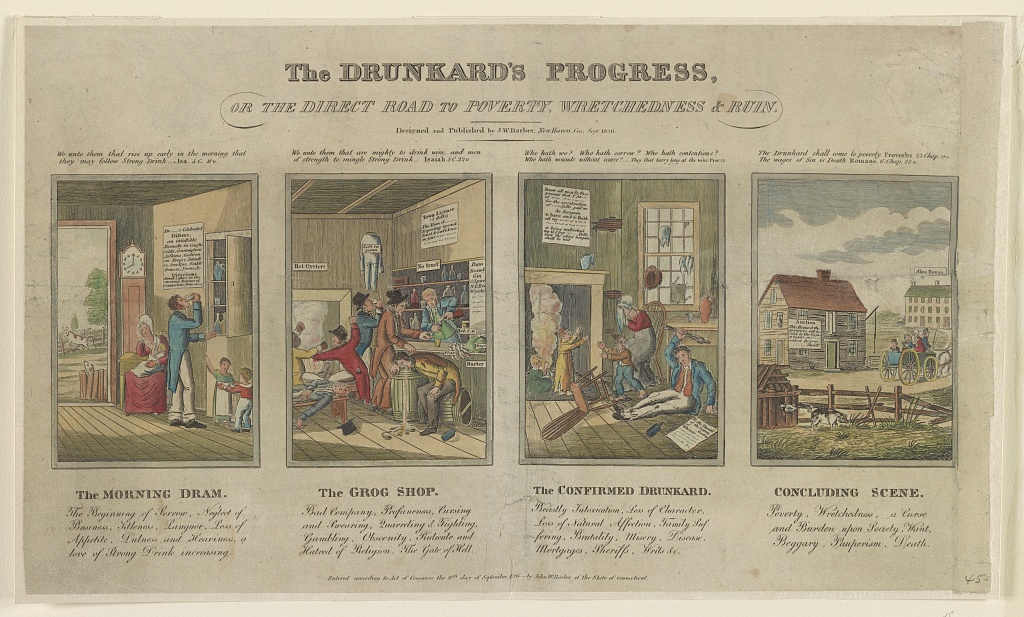

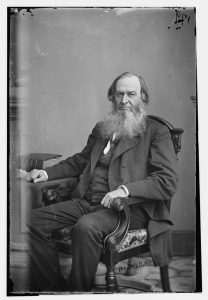

Ever since I was a kid, I’ve been aware of the saying, “If March comes in like a lion, it goes out like a lamb” (and I thought vice versa, but that seems to return a lot fewer search results). According to documentation at the Library of Congress, a 19th century American social reformer had a different take on the changeable month. Gerrit Smith wanted March to come in dry, stay dry, and go out dry, not just in March but in every month and in every year. Alcohol was freely and legally available for sale in much of the United States 150 years ago, so Mr. Smith took a couple steps to change that in March 1870.

On March 2nd he reported the relative success of the New York State Anti-Dramshop Party in a local election in the town of Smithfield (itself dry since 1842). I don’t think it won any particular race, but it did better than the Democrats. Gerrit Smith referred to both the Democrats and Republicans as dramshop parties because neither was confronting the evil of dramselling, even though both parties had non-drinking members. The name of his party also indicated its narrow focus. “The great principle on which our party is founded and the happily-chosen name of our party afforded us a great advantage in arguing for our ticket. This principle—viz. the duty of Government to protect person and property — none could gainsay. Nor could any deny that it grossly violates this duty, when it establishes or permits the dramshop.” The party didn’t want to criminalize drinking at home, or even the manufacture and importation of alcohol because a ban on selling alcoholic drinks would dampen the demand so much that making and/or importing wouldn’t be profitable.

Mr. Smith saw a potential rift in the temperance movement between his party’s purpose and those who wanted to make any use of alcohol illegal:

Just here, is one of the very greatest perils of our cause. Just here, is where the friends of temperance are divided—perhaps, fatally divided. Whilst many of them would wage political war upon dramselling only, many of them would wage it against alcohol, every where. Such universal war would, probably, result in nothing but a reaction against the cause of temperance. On the other hand, if the war is against dramselling only, it will be espoused by tens of thousands, who, though they may continue to drink liquor at their homes, are, nevertheless, too much the friends of peace and order and too studious of the safety of person and property, to be patient with the dramshop. Moreover, such of them, as have young sons or young grandsons, take no pleasure in the thought of their growing up under the influence of the dramshop.

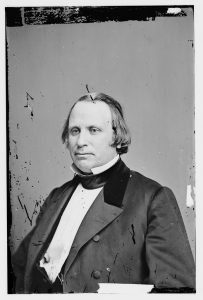

In a letter to Henry Wilson dated March 29, 1870, Gerrit Smith picked a bone with his fellow abolitionist and temperance supporter. He criticized a paper by the U.S. Senator from Massachusetts for not getting down to the nitty-gritty of politicizing the temperance movement by abolishing the dramshop. It wasn’t enough for the church to be in favor of temperance – it had to focus on voting the dramshop out of existence. Any movement that combined temperance with protestantism would be ineffective for eliminating the use of alcohol because the temperance movement needed support from people of all religions:

What in your paper before me most surprises and pains me is its perfect silence in respect to voting. For years, you were earnestly engaged in the work of voting slavery to death. Hence you connected yourself with an independent anti-slavery political party, and eloquently summoned your fellow citizens to do likewise. Why is it that you are not now at work to get the dramshop voted out of existence? I notice that you speak of the labor we have had with slavery and with its consequences as a “political” labor, and of that we have with temperance as a “moral” one. I beg you to inform the public of your grounds for this distinction. Is not the dramshop as much as slavery the creature of law? — and is not political action to shut it up as necessarily and as loudly called for, as it was to terminate slavery?

Your reliance for carrying forward the cause of temperance is on the reviving of an interest in it in the church. “The church must take up the matter,” say you in capitals. Now, if you had said: “the church must take up the matter of voting for temperance or, in other words, of voting against the dramshop,” my whole heart would have fallen in with your injunction. I like sermons and prayers, when their avowed end is to promote the doing of the work, that is to be done: — but I loathe them when they are made a substitute for doing it. A church, that expressly preaches and prays for men to vote the shutting up of the dramshop, is a church that I like. But such a church is not common. Nay, uncommon is the church, whose votes do not go to keep open this overflowing fountain of the heaviest curses. You refer to the guilty conduct of the church in our old struggle with slavery. Guilty wherein? She failed not to preach and pray against oppression. Her guilt was in clinging to pro-slavery parties and refusing to testify against slavery at the polls. Similar to this is her guilt in the matter of the dramshop and drunkenness; —and you must pardon me for adding that you, instead of entirely ignoring the wickedness of her dramshop voting, are, from your influential position in the church, under special obligation to bring home to her and press upon her this great wickedness. Would that, instead of writing this paper which I am criticising, you had called on the church to persuade all her voters to join the national political party organized last September for the suppression of dramselling. Some of these voters are joining it. Some of them are still foolish enough to believe that their dramshop parties will yet abolish the dramshop, just as there were persons who were foolish enough to believe that the old Whig and Democratic parties would abolish slavery. To hang upon these parties which, as a general remark, have not the least idea of ever making war upon the dramshop, is, surely, a very poor way to help temperance. Some of these voters would quit their dramshop parties to join a party (if there were such a one) which goes against the dramshop and also against certain things that they greatly dislike. But the party, which fights the dramshop, will have its hands full, though it shall fight nothing else. It will need, too, all the help it can get — Catholic as well as Protestant voters; men of whatever views of the Common School; Jews, Seventh day Baptists and No-Sabbath men as well as Sunday men. It is true that a party for temperance and protestantism might, as it is claimed it would, “sweep the State.” Such a party would, however, sweep it not with temperance — but with a protestant frenzy. It would bring no help, but, on the contrary, immense harm to temperance. No good whatever would come of such a party; whilst the sectarian animosity it would engender is an evil beyond computation. I have now referred to some of the different courses of different church members. I close under this head with saying that a large share of the church members manifest no interest whatever in the cause of temperance.

_____________

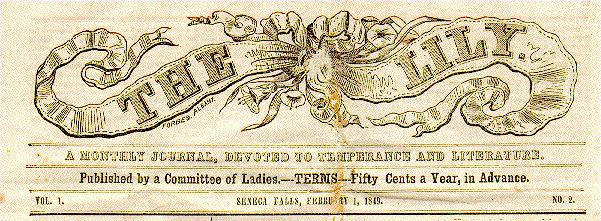

It seems that both Gerrit Smith and Henry Wilson prioritized progressive causes. Since slavery had been abolished and reconstruction was “substantially complete,” temperance should take center stage (Mr. Smith also mentioned repudiation). Women’s rights was another movement intertwined with abolition and temperance, as Seneca County Historian Walt Gable pointed out in an excellent article about Amelia Bloomer (Finger Lakes Times, March 29, 2020, page 4B). She got married to a local newspaper publisher and moved to Seneca Falls, New York in 1840. At the wedding reception she “sweetly refused to drink wine.” Seneca Falls would have made Gerrit Smith very happy in 1842 when it passed a law forbidding the sale of liquor. She became a member of the Ladies Total Abstinence Society of Seneca Falls that formed in 1848. That Society began publishing The Lily in 1849; from 1850 Amelia Bloomer was editor and publisher until she sold the paper in 1854. The Lily publicized the newfangled pants with knee-length dress, which became known as “bloomers,” even though Amelia didn’t invent them. On May 12, 1851 Bloomer introduced Susan B. Anthony to Elizabeth Cady Stanton after a public program during which William Lloyd Garrison and a British abolitionist spoke. Sometime after their first meeting Anthony was invited to spend several days at the Stanton home. “Thus began the great working collaboration between Anthony and Stanton in both the temperance and women’s rights causes.” In 1853 the Bloomers began moving west and ended up in Iowa: “During the Civil War, she [Amelia] started the Soldier’s Aid Society of Council Bluffs to help Union soldiers.”