On March 2, 1867 Andrew Johnson vetoed two bills as the 39th Congress was wrapping up its business. Both vetoes were immediately overridden by Congress.

The Tenure of Office Act limited the President’s power to terminate certain appointees without the Senate’s consent:

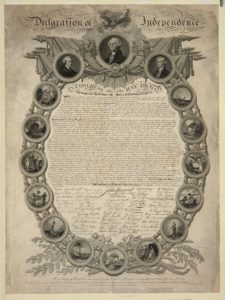

That every person holding any civil office to which he has been appointed, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, and every person who shall hereafter be appointed to any such office and shall become duly qualified to act therein, is and shall be entitled to hold such office until a successor shall have been appointed by the President, with the advice and consent of the Senate, and duly qualified; and that the Secretaries of State, of the Treasury, of War, of the Navy, and of the Interior, the Postmaster-General, and the Attorney-General shall hold their offices respectively for and during the term of the President by whom they may have been appointed and for one month thereafter, subject to removal by and with the advice and consent of the Senate. [from the veto message]

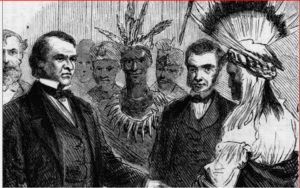

Congress was especially interested in protecting Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, the most radical member of President Johnson’s cabinet. According to Hans L. Trefousse, all cabinet members opposed the bill, including the Secretary of War. However, Mr. Stanton refused the president’s request that he write the veto message because he was real busy and the rheumatism in his arm was acting up. William H. Seward wrote the “exemplary” veto message (at Project Gutenberg). John Bigelow watched the Congressional override proceedings and was impressed by the contempt Congress had for the president. [1]

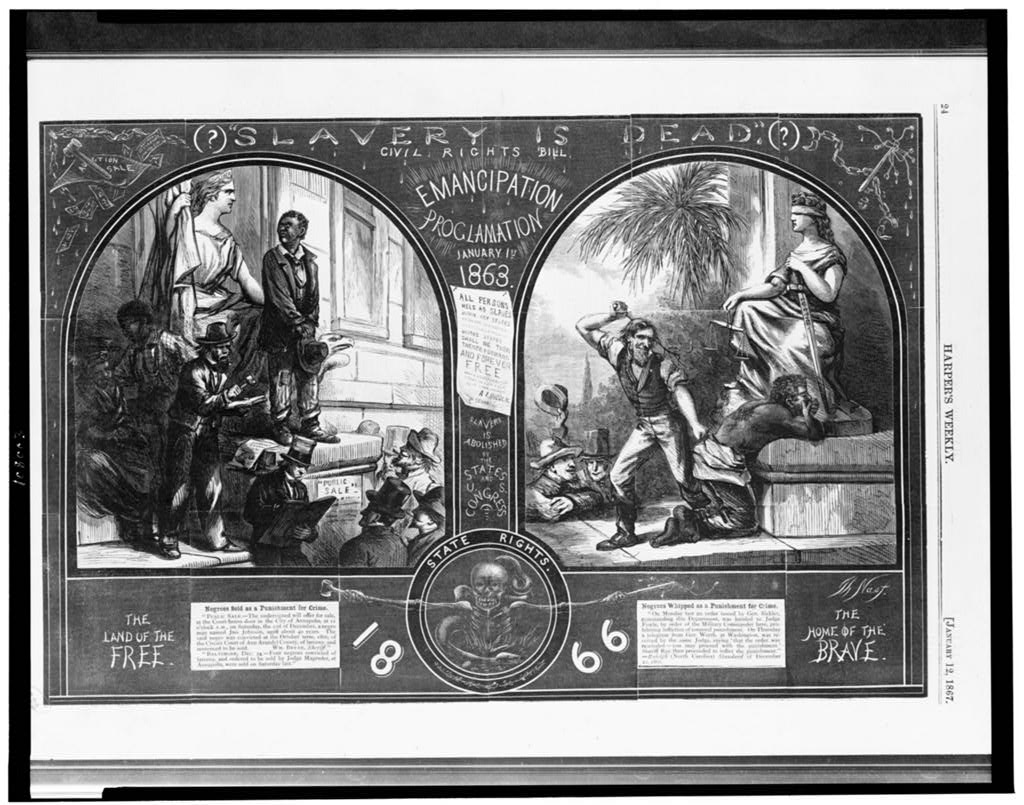

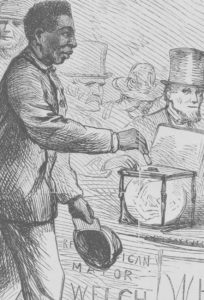

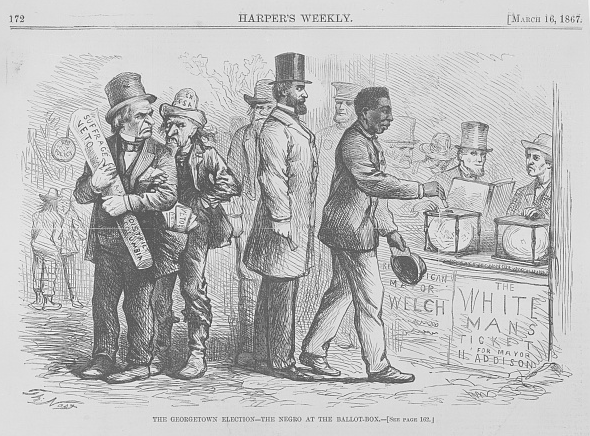

President Johnson also vetoed “An act to provide for the more efficient government of the Rebel States”, which was the first of the Reconstruction Acts. The first law divided the South into five military districts. “In addition, Congress required that each state draft a new state constitution, which would have to be approved by Congress. The states also were required to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution and grant voting rights to black men.”

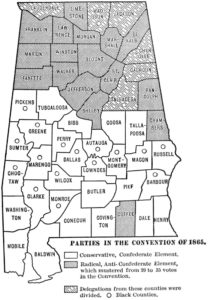

Here’s a Southern take on the law by Walter L. Fleming in his 1905 Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama (pages 473-474):

The Military Reconstruction Bills

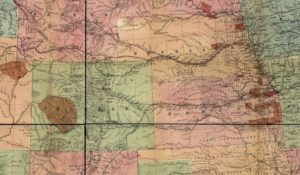

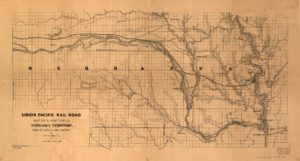

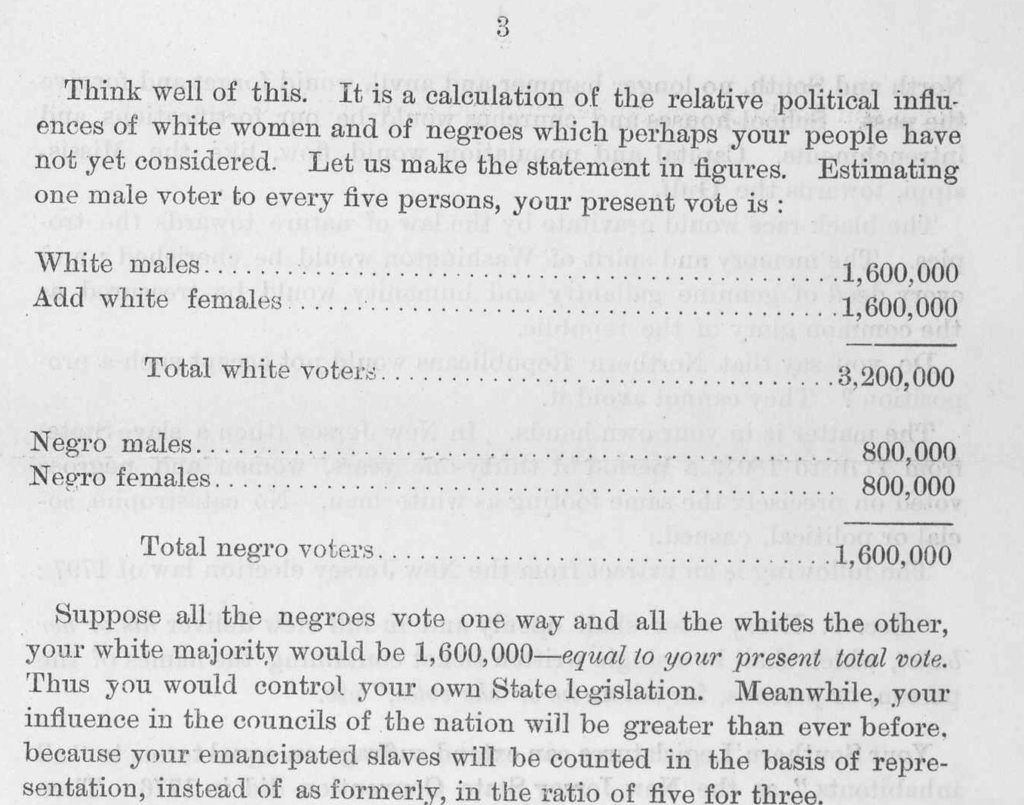

The Radicals in Congress triumphed over the moderate Republicans, the Democrats, and the President, when, on March 2, 1867, they succeeded in passing over the veto the first of the Reconstruction Acts. This act reduced the southern states to the status of military provinces and established the rule of martial law. After asserting in the preamble that no legal governments or adequate protection for life and property existed in Alabama and other southern states, the act divided the South into five military districts, subject to the absolute control of the central government, that is, of Congress. Alabama, with Georgia and Florida, constituted the Third Military District. The military commander, a general officer, appointed by the President, was to carry on the government in his province. No state interference was to be allowed, though the provisional civil administration might be made use of if the commander saw fit. Offenders might be tried by the local courts or by military commissions, and except in cases involving the death penalty, there was no appeal beyond the military governor. This rule of martial law was to continue until the people should adopt a constitution providing for enfranchisement of the negro and for the disfranchisement of such whites as would be excluded by the proposed Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. As soon as this constitution should be ratified by the new electorate (a majority voting in the election) and the constitution approved by Congress, and the legislature elected under the new constitution should ratify the proposed Fourteenth Amendment, then representatives from the state were to be admitted to Congress upon taking the “iron-clad” test oath of July 2, 1862. And until so reconstructed the present civil government of the state was provisional only and might be altered, controlled, or abolished, and in all elections under it the negro must vote and those who would be excluded by the proposed Fourteenth Amendment must be disfranchised.

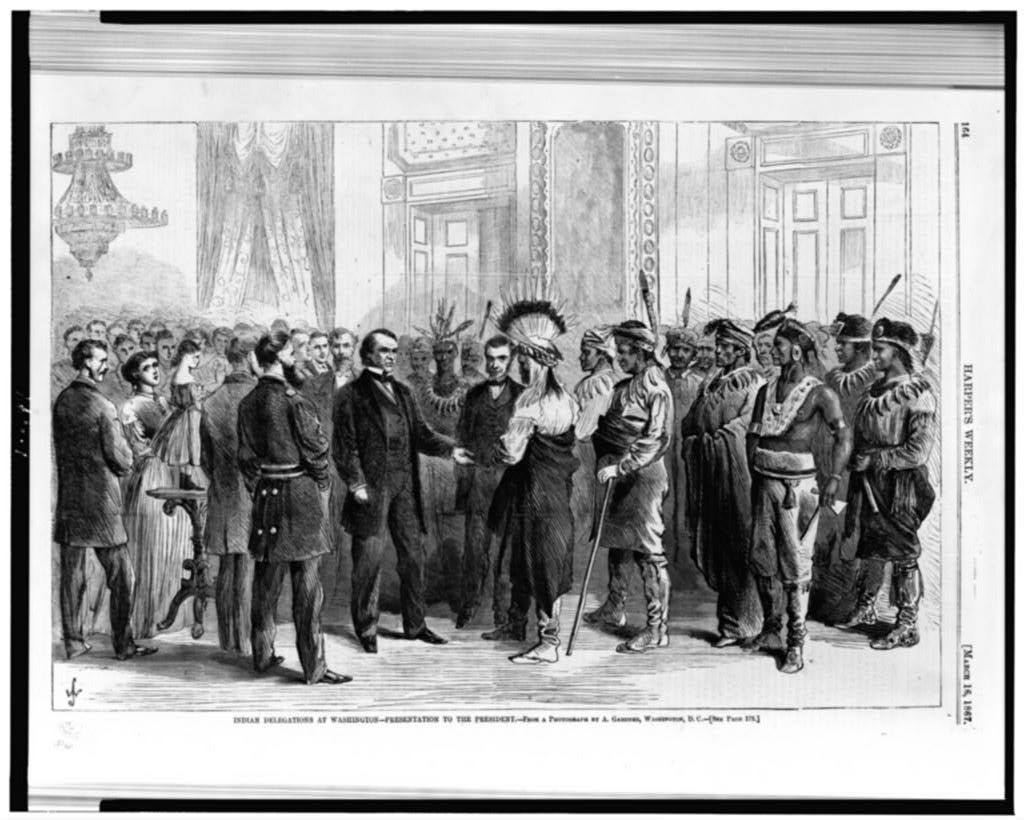

The President at once (March 11, 1867) appointed General George H. Thomas to the command of the Third Military District, with headquarters at Montgomery, but the work was not to General Thomas’s liking, and at his request he was relieved, and on March 15 General Pope was appointed in his place. Pope was in favor of extreme measures in dealing with the southern people and stated that he understood the design of the Reconstruction Acts to be “to free the southern people from the baleful influence of old political leaders.”

The act of March 2 did not provide for forcing Reconstruction upon the people. If they wanted it, they might initiate it through the provisional governments, or if they preferred, they might remain under martial law. While all people were anxious to have the state restored to the Union, most of the whites saw that to continue under martial law, even when administered by Pope, was preferable to Reconstruction under the proposed terms. Consequently the movement toward Reconstruction was made by a very small minority of the people and had no chance whatever of making any headway.

You can also read the veto message of the Military Government bill at Project Gutenberg. Mr. Trefousse wrote that President Johnson wrote the document with the help of Jeremiah S. Black and Attorney General Henry Stanbery[2]

An editorial in the March 5, 1867 issue of The New-York Times reviewed the bills passed at the end of the 39th Congress:

The Session.

It’s the same old story. A session begun lazily winds up with speed of a high-pressure engine. …

The settlement of the reconstruction question would alone invest it with importance. The mode of settlement is not as we would have it. It conflicts with preconceived notions of republicanism, and awakens a painful, anxious interest in the future of the South. But, rough though it be – harsh and despotic as it undeniably is – it is preferable to prolonged uncertainty or delay. Even Radical reconstruction, with military government as its initiatory process and universal negro suffrage as its inevitable object, is better than the indefinite exclusion of ten States, or the absence of specific declarations touching their reorganization. Congress has fixed its policy, and with the President’s help, must work it out. From this responsibility there can be no escape. The work must go forward from this day, on the basis constructed; and the wisdom or folly of the policy must be determined by its fruit. How it shall operate upon the South – whether as an irritant, necessitating the vigorous exercise of the military power, or as a stimulant, producing the healthy counteraction which shall render military authority unnecessary – depends upon the South itself. It may resist and suffer, or it may submit and regain peace and prosperity. Congress has acted intelligibly, and in a certain sense thoroughly according to the judgment of a majority, and though the Southern people may lose, they cannot possibly profit, by failing to comply with the terms prescribed. …

Waging a quiet but uncompromising war with the President, Congress has not only enacted a measure crippling his power of removing and appointing in the civil branches of the Government, but has also tacked to the Army Appropriations Bill a clause diminishing his authority as Commander-in-Chief over the General, and otherwise over the army. An opinion prevailed that the latter measure would encounter a pocket veto. The exigencies of the service, however, rendered the loss of the appropriation undesirable, and the President yesterday signed the bill under protest. …

Congress added to the military appropriations a requirement that the president issue orders to the army through the general-in-chief (Ulysses S. Grant), who had to be stationed in Washington, D.C. [3]

![Johnson's Georgetown and the city of Washington : the capital of the United States of America. (New York : A.J. Johnson, [1867] ; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/88693495/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/dc1867-1024x805.jpg)

![[Gettysburg, Pa. Alfred R. Waud, artist of Harper's Weekly, sketching on battlefield] (by Timothy H. O'Sullivan, 1863 July; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/cwp2003000198/PP/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/00074v-300x234.jpg)