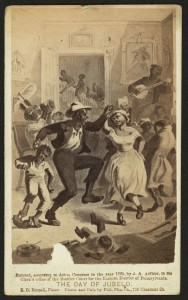

The National Government “has freed the four millions of slaves by its own deliberate acts, and it is bound to take care that this freedom shall benefit, and not injure them.” – hopefully with the support of the state governments in the South and with the help of philanthropic organizations.

From The New-York Times June 6, 1865:

The Government and the Freedmen.

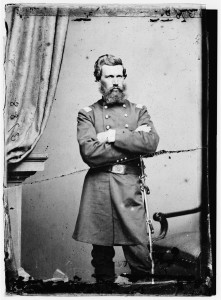

The opinion has recently been expressed by Maj.-Gen. JOSEPH JOHNSTON, one of the foremost of the Southern leaders, that a social war between the whites and blacks of the South is probable. There is reason to fear that this expectation widely prevails throughout the South. It was an universally accepted axiom there, long before the rebellion, that emancipation would result in one of two things–either amalgamation or extermination. That was the feeling even two or three generations ago, when slavery was admitted to be a positive evil; and it was the standing argument against disturbing the existing order of things. In fact the North, too, had the same opinion. Four years ago there were probably not ten thoughtful men in the North who had the conviction t[???] immediate and universal emancipation would be safe for Southern society. It was this fear of the social danger that would result which constrained Mr. LINCOLN to insist so strongly as he at first did upon supplementing emancipation with some great plan of colonizing the freedmen abroad.

Whether emancipation is or is not fraught with this danger cannot be determined. Sufficient time has not elapsed since the close of the war for the two races to realize their new relations, and develop the spirit which will hereafter actuate them. Both races now find themselves wholly occupied in keeping themselves and those dependent upon them from starvation. All evil passions are absorbed by the physical necessity of cooperating for the common subsistence. But it is by no means certain that peace would continue after the present pinch has passed away. The whites, as soon as they can breathe a little more freely, would naturally reassert their superiority, and try to resume their old habits of control; and the blacks would naturally make the most of their new independence, and indulge themselves largely in defiance and opposition. There might, perhaps, be motives of self-interest that would restrain all such tendencies. If men were always governed by what is really for their own good, there would be no cause for any apprehension that the two races in our Southern States would not adapt themselves to each other and live in harmony. But the whites have not the pliant disposition, nor the blacks the wise understanding that can guarantee any such result. The only safe way is to assume that danger may arise, and to take timely measures to avert it.

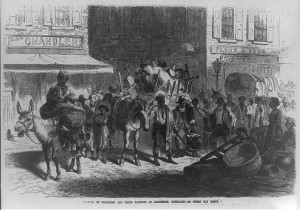

“Arrival of freedmen and their families at Baltimore” (Frank Leslie’s September 30, 1865 (Library of Congress))

This business must devolve primarily upon the National Government. It is, in fact, a responsibility which the government cannot avoid, even if it would. It has freed the four millions of slaves by its own deliberate acts, and it is bound to take care that this freedom shall benefit, and not injure them. To transport them from the country is impracticable; and even if it were not, it would be barbarous to drag them from the soil against their will. Nor can the government leave them, without help or guidance, adrift in the social chaos around them, or at the mercy of the stronger race. This would be a flagrant inhumanity. There is no alternative but for the government both to protect and to direct them. The last Congress never did a wiser thing than to establish a special bureau in the War Department for this particular purpose. Yet this bureau will have most difficult work to accomplish. Its means are greatly disproportioned to the end it must secure. With the close of the war, of course all war powers must cease. With the rehabilitation of the Southern States, of course all of the reserved rights of the States must revive. These rights, it has always been recognized, embrace all the domestic affairs of each State. It is not easy to see how the National Government could constitutionally exercise a particular control over a certain portion of the population of a State, not extending to all. Again, it is not easy to see how the National Government could constitutionally maintain a system of education for the blacks, such as is necessary to fit them for permanent, orderly, self-sustaining freedom. Certainly the power of providing for popular instruction is not among the grants to the government enumerated in the Federal constitution. The only practicable method of meeting the various difficulties is, on the one hand, for the government to secure, as far as possible, an understanding with the States before they are restored to their position, that they will not obstruct but cooperate with it in its efforts to protect and keep in check the freedmen; and, on the other hand, for it to cooperate with benevolent associations which will take it upon themselves to give to the freedmen industrial guidance, mental and moral instruction. The Southern people have as yet shown no signs of opposition to the management of the freedmen by the Washington authorities. With the regulations that prevent the freedmen from crowding into the cities, and compel them to work in their old neighborhoods either for themselves or on hire, the whites are every way satisfied. It is believed that the loyal men, into whose hands the government of all the Southern States will go, will recognize the policy of furthering, by legislative enactments, the policy of the National Government, not only in preventing vagabondage, but in improving the general condition of the negro.

But the government must find its main help in the voluntary associations for the benefit of the freedmen. There is no object that begins to appeal to every patriot and philanthropist with any such force as this. It is the universal testimony of all officers and civilians who have had the opportunity of observing, that the freedmen are, to a surprising degree, eager to learn, and quick to learn; and that when they have any suitable direction, and the means of working, they adapt themselves to their new condition with extraordinary facility. But they are now in the extremest need of teachers, and sympathetic guardians, and the implements of labor. The government has made a beginning toward the supply of implements, by directing that all the shovels and axes, and other tools, of the disbanded armies, shall be turned over to the use of the freedmen. It has done most admirably, too, in detailing so able and so thoroughly faithful an officer as Major-Gen. HOWARD to the management of the Freedmen’s Bureau. The army officers which he will detail for the local superintendencies will doubtless be men of his own true stamp. But, at most, the active sphere of that bureau is very limited. It is indispensable as a protector and an ally, but the main work must be done by private agencies. Hundreds of teachers ought to be sent South by the Northern people before this year closes. Hundreds of thousands of dollars ought to be raised by voluntary contributions, for relieving the physical necessities of the freedmen, furnishing them with the implements necessary to make a start in life, and paying the slender salaries of the teachers. This is an imperative duty. The manner in which it is met will be a practical test of the real friendship of the North for the race, over whom more words of compassion have been uttered than for all the world besides. As we act, so will it be determined whether our anti-slavery spirit came from hate of the slaveholder or love of the slave.

You can read more about the Arlington Freedman’s Village at the National Park Service

![Joseph E. Johnson [i.e., Johnston] / engraved & published by William Sartain, 728 Sansom St., Philada. (http://www.loc.gov/item/91732234/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/3c03202v-240x300.jpg)