150 years ago Harper’s Weekly published a brief bio of a member of the 43rd Congress. From its February 14, 1874 issue of :

THE HON. ROBERT B. ELLIOTT.

The South Carolina district that for many years sent JOHN C. CALHOUN to Congress is now represented in that body by the Hon. ROBERT BROWN ELLIOTT, who is of unmixed African blood. He was born in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1842, received his primary education at private schools, and afterward studied at Eton College, England, where he graduated in 1859. From Massachusetts he went to Charleston, South Carolina, in 1866, and began his new career there as a type-setter in the office of a newspaper edited by his present colleague, Mr. RANSIER. He has a natural gift for oratory, which has been cultivated by large experience on the stump. “His voice,” says one who has listened to his oratory, “is full and agreeable, and in his pronunciation he displays far less of the peculiarities of the negro dialect than many of the Southern white members. His sentences are constructed with an obvious regard for euphonious sound, and if any fault were to be found in his manner of speaking, it would be that he falls into too much of a cadenced delivery.”

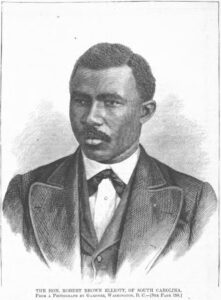

Mr. ELLIOTT’s name was brought into prominence by his speech on the Civil Rights Bill, delivered on the 6th of January, in reply to Mr. HARRIS, of Kentucky. Those who heard him declared the speech to be the most remarkable effort yet made by a colored member of Congress. He read his remarks from manuscript, but this did not detract from their force as from that of Mr. STEPHENS’s speech of the day before, for he made use of all the orator’s art, voice, and gesture. He got a much more attentive hearing from the House than did the great Georgian, and was more than once applauded by the members, whose hand-clappings were at once echoed from the galleries, packed with colored people. When he sat down the applause was deafening, and many members rushed forward to shake his hand and congratulate him. A portrait of Mr. ELLIOTT is given on the preceding page.

According to the South Carolina Encyclopedia, Peggy Lamson, the modern biographer of Robert B. Elliott, “believes that he was born on August 11, 1842, in Liverpool, England, of unknown West Indian parents. Contemporary accounts state that he was born in Boston, educated at High Holborn Academy in London, and graduated from Eton College in 1859, although no evidence survives to corroborate these claims. It does seem likely that he did enjoy a substantial degree of formal education, since Elliott was universally acknowledged to be highly literate and learned.” Also regarding the Harper’s piece, I don’t see a Mr. Harris from Kentucky.

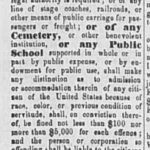

Stephens and Elliott were debating the legislation that would eventually become the Civil Rights Act of 1875. The original original bill was introduced in 1870 by Charles Sumner and “outlawed racial discrimination in juries, schools, transportation, and public accommodations.” The Republican leaders had to weaken the bill’s provisions to get enough support for it. The 1875 law “- which only passed after all references to equal and integrated education were stripped completely — failed to have any lasting effect. The Supreme Court struck down the 1875 Civil Rights Bill in 1883 on the grounds that the Constitution did not extend to private businesses.”

You can read more about the Stephens-Elliott debate at the Library of Congress. On January 6, 1874 Elliott directly responded to Stephens’ speech the day before:

Now sir, recurring to the venerable and distinguished gentleman from Georgia, [Mr. Stephens,] who has added his remonstrance against the passage of this bill, permit me to say that I share in the feeling of high personal regard for that gentleman which pervades this House. His years, his ability, and his long experience in public affairs entitle him to the measure of consideration which has been accorded to him on this floor. But in this discussion, I cannot and I will not forget that the welfare and rights of my whole race in this country are involved. When, therefore, the honorable gentleman from Georgia lends his voice and influence to defeat this measure, I do not shrink from saying that it is not from him that the American House of Representatives should take lessons in matters touching human rights or the joint relations of the State and national governments. While the honorable gentleman contented himself with harmless speculation in this study, or in the columns of a newspaper, we might well smile at the impotence of his efforts to turn back the advancing tide of opinion and progress; but when he comes against upon this national arena, and throws himself with all his power and influence across the path which leads to the full enfranchisement of my race, I meet him only as an adversary; nor shall age or any other consideration restrain me from saying that he now offers this Government, which he has done his utmost to destroy, a very poor return for its magnanimous treatment, to come here and seek to continue, by the assertion of doctrines obnoxious to the true principles of our Government, the burdens and oppressions which rest upon five millions of his countrymen who never failed to lift their earnest prayers for the success of this Government when the gentleman was seeking to break up the Union of these States and to blot the American Republic from the galaxy of nations [Loud applause]. (Congressional Record, House, 43rd Cong., 1st sess. (6 January 1874): 409.)

Sir, it is scarcely twelve years since that gentleman shocked the civilized word by announcing the birth of a government which rested on human slavery as its corner-stone. The progress of events has swept away that pseudo-government which rested on greed, pride, and tyranny; and the race who he then ruthlessly spurned and tramped on are here to meet him in debate, and to demand that the rights which are enjoyed by their former oppressors – who vainly sought to overthrow a Government for which they could not prostitute to the base uses of slavery – shall be accorded to those who even in the darkness of slavery kept their allegiance to freedom and the Union. Sir, the gentleman from Georgia has learned much since 1861; but he is still a laggard. Let him put away the entirely false and fatal theories which have so greatly marred an otherwise enviable record. Let him accept, in its fullness and beneficence, the great doctrine that American citizenship carries with it every civil and political right which manhood can confer. Let him lend his influence, with all masterly ability, to complete the proud structure of legislation which makes this nation worthy of the great declaration which heralded its birth, and he will have done that which will most nearly redeem his reputation in the eyes of the world, and best vindicate the wisdom of that policy which has permitted him to regain his seat upon this floor.

(Congressional Record, House, 43rd Cong., 1st sess. (6 January 1874): 410.)

This Library of Congress article provides links to Elliott’s full speech in the Congressional Record and an article about the 1875 Civil Rights Act. You can read Alexander Stephens’ January 5th speech that starts here in the Congressional Record.

According to Eric Foner, “Seven blacks sat in the Forty-Third Congress, and all spoke with vigor and eloquence, on the Civil Rights Bill. Before galleries crowded with black spectators, their speeches invoked both personal experience and the black political ideology that had matured during Reconstruction. Several related their own ‘outrages and indignities.’ Joseph Rainey had been thrown from a Virginia streetcar, John R. Lynch forced to occupy a railroad smoking car with gamblers and drunkards, Richard H. Cain and Robert B. Elliott excluded from a North Carolina restaurant, …” [Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877. New York: HarperPerenial ModernClassics, 2014. Pages 399-400.]

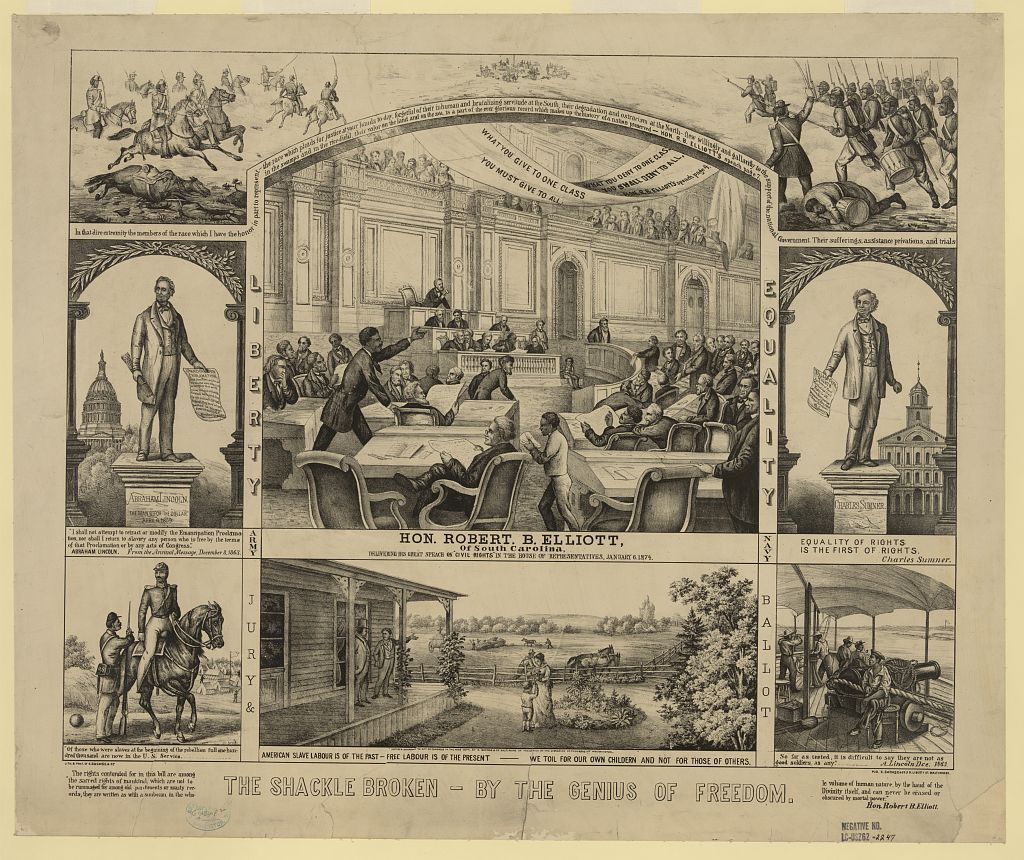

From the Library of Congress: The Shackle Broken, “South Carolina representative Robert B. Elliott’s famous speech in favor of the Civil Rights Act, delivered in the House of Representatives on January 6, 1874, is memorialized here. The Act, which guaranteed equal treatment in all places of public accommodation to all people regardless of their “nativity, race, color, or persuasion, religious or political,” was passed on March 1, 1875. The central image shows Congressman Elliott speaking from the floor of the House of Representatives. Hanging from the ceiling is a banner with a quotation from his speech: “What you give to one class you must give to all. What you deny to one class. You deny to all.” Above are two Civil War scenes of black troops in action. On the left is a full-length statue of Abraham Lincoln, holding a bundle of arrows and his Emancipation Proclamation, standing before the U.S. Capitol. On the right is another statue, of Civil Rights advocate Charles Sumner holding the “Bill of Civil Rights,” in front of Faneuil Hall in Boston. Below Sumner are his words, “Equality of rights is the first of rights.” Beneath the central scene is a view of a small farm with its black owner, family, and laborers. The caption below is “American Slave Labour is of the Past – Free Labour is of the Present–We Toil for our Own Children and Not for Those of Others.” At the far left are two black soldiers, and on the right black sailors. Below them are Lincoln’s words, “Of those who were slaves at the beginning of the rebellion full one hundred thousand are now in the U. S. Service” and “So far as tested, it is difficult to say they are not as good soldiers as any.” The words “Army,” “Navy,” “Jury,” “Ballot,” “Liberty,” and “Equality” are inscribed in the borders. Further extracts from Elliott’s speech appear throughout.”; you can read more about it at the Smithsonian, its National Museum of African American History & Culture.

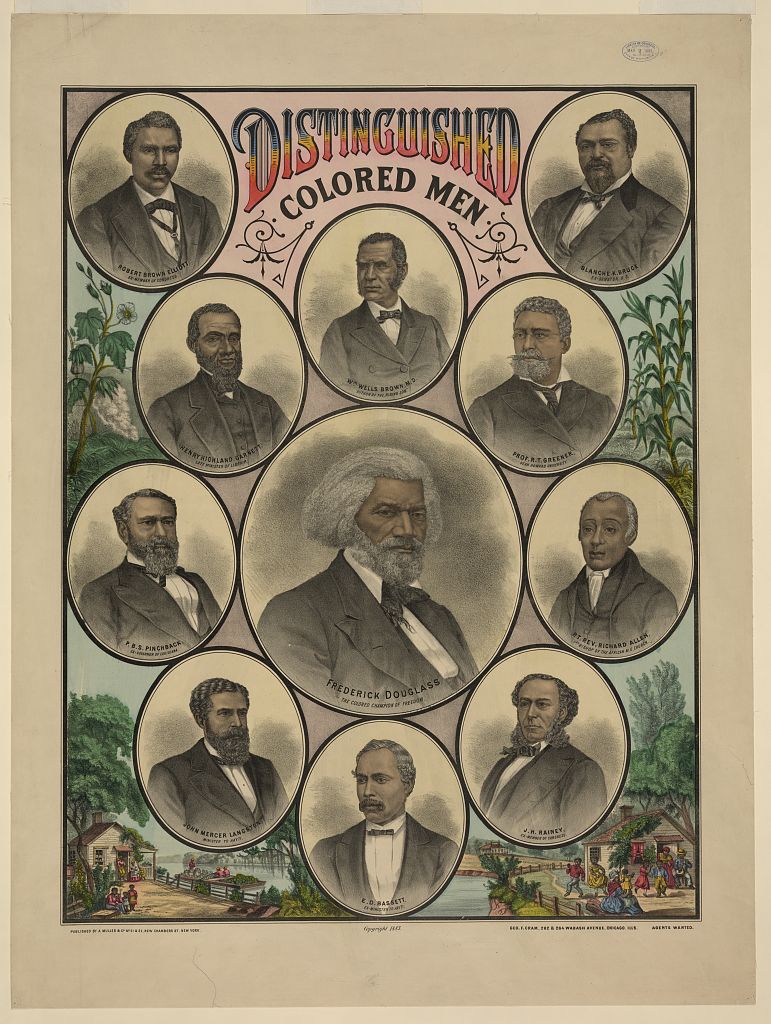

Also from the Library of Congress: the Currier & Ives 1872 image of “The first colored senator and representatives – in the 41st and 42nd Congress of the United States”; Frederick Douglass and other Distinguished Colored Men, c1883 – according to the New York Public Library, Frederick Douglass wrote to a newspaper when Elliott died, “…I, with thousands who knew the ability of young Elliott, was hoping and waiting to see him emerge from his late comparative obscurity, and take his place again in the halls of Congress. But alas! He is gone, and we can only hope that the same power that gave us one Elliott, will give us another in the near future. Frederick Douglass, Washington, D.C. Aug 30.” ; an editorial on page 2 of the January 19, 1874 issue of The Democrat in Weston, West Virginia, which saw the Civil Rights legislation as “The Beginning of the End.”

I got the Harper’s Weekly article and image from HathiTrust on pages 149 and 150. I put the portrait from page 150 in the first paragraph of the article.

The January 1874 clipping also comes from the same link at HathiTrust.