For, disguise it as we may, the United States government really holds and exercises the power which gives vitality to the preliminaries of reconstruction, and it is therefore responsible for all evils in the future which shall spring from its neglect or injustice in the present.

Earlier this month Seven Score and Ten published a letter written by Mississippi politician Henry S. Foote that advocated black suffrage as a necessary policy for the South to be reunited to the North:

We must, in order to assure our own return to liberty and happiness, not only recognize the colored denizens of the South as now free, but we must allow them the same means of preserving their freedom that we ourselves desire to possess. They must be freedmen in fact as well as in name. We must consent to their being invested with the elective franchise; and this must be done, too, no matter what cherished notions we may entertain in regard to the mental inferiority of those whom some of us have heretofore regarded as the doomed posterity of Ham.

150 years ago a Northern publication made a similar case. I didn’t read all 6200 words (without pictures!), but here are a few excerpts from The Atlantic Monthly, VOL. XVI.—AUGUST, 1865.—NO. XCIV.:

RECONSTRUCTION AND NEGRO SUFFRAGE.

The submission of the Rebel armies and the occupation of the Rebel territory by the forces of the United States are successes which have been purchased at the cost of the lives of half a million of loyal men and a debt of nearly three thousand millions of dollars; but, according to theories of State Rights now springing anew to life, victory has smitten us with impotence. The war, it seems, was waged for the purpose of forcing the sword out of the Rebel’s hands, and forcing into them the ballot. At an enormous waste of treasure and blood, we have acquired the territory for which we fought; and lo! it is not ours, but belongs to the people we have been engaged in fighting, in virtue of the constitution we have been fighting for. The Federal government is now, it appears, what Wigfall elegantly styled it four years ago,—nothing but “the one-horse concern at Washington”: the real power is in the States it has subdued. We are therefore expected to act like the savage, who, after thrashing his Fetich for disappointing his prayers, falls down again and worships it. Our Fetich is State Rights, as perversely misunderstood. The Rebellion would have been soon put down, had it been merely an insurrectionary outbreak of masses of people without any political organization. Its tremendous force came from its being a revolt of States, with the capacity to employ those powers of taxation and conscription which place the persons and property of all residing in political communities at the service of their governments. And now that characteristic which gave strength to the Rebel communities in war is invoked to shield them from Federal regulation in defeat. We are required to substitute technicalities for facts; to consider the Rebellion—what it notoriously was not—a mere revolt of loose aggregations of men owing allegiance to the United States; and to hold the States, which endowed them with such a perfect organization and poisonous vitality, as innocent of the crime. The verbal dilemma in which this reasoning places us is this: that the Rebel States could not do what they did, and therefore we cannot do what we must. Among other things which it is said we cannot do, the prescribing of the qualifications of voters in the States occupies the most important place; and it is necessary to inquire whether the Rebel communities now held by our military power are States, in the sense that word bears in the Federal Constitution. If they are, we have not only no right to say that negroes shall enjoy in them the privilege of voting, but no right to prescribe any qualifications for white voters. …

[Several arguments that the rebel states are currently not Constitutional states and that the federal government has the right and power to decide who has the right to vote in the rebel territories]

It is often said, that, although the Federal government may have the right and power to decide who shall be considered “the people” of the Rebel States, in so important a matter as the conversion of them into States of the Federal Union, it is still politic and just to make the qualifications of voters as nearly as possible what they were before the Rebellion. Conceding this, we still have to face the fact, that a large body of men, held before the war as slaves, have been emancipated, and added to the body of the people. They are now as free as the white men. The old constitutions of the Slave States could have no application to the new condition of affairs. The change in the circumstances, by which four years have done the ordinary work of a century, demands a corresponding change in the application of old rules, even admitting that we should take them as a guide. Having converted the loyal blacks from slaves into the condition of citizens of the United States, there can be no reason or justice or policy in allowing them to be made, in localities recently Rebel, the subjects of whites who have but just purged themselves from the guilt of treason.

The question of negro suffrage being thus reduced to a question of expediency, to be decided on its own merits, the first argument brought against it is based on the proposition, that it is inexpedient to give the privilege of voting to the ignorant and unintelligent. This sounds well; but a moment’s reflection shows us that the objection is directed simply against deficiencies of education and intelligence which happen to be accompanied with a black skin. Three fifths or three fourths of the poor whites of the South cannot read or write; and they are cruelly belied, if they do not add to their ignorance that more important disqualification for good citizenship,—indisposition or incapacity for work. In general, the American system proceeds on the idea that the best way of qualifying men to vote is voting, as the best way of teaching boys to swim is to let them go into the water. “Our national experience,” says Chief-Justice Chase, in a letter to the New Orleans freedmen, “has demonstrated that public order reposes most securely on the broad base of Universal Suffrage. It has proved, also, that universal suffrage is the surest guaranty and most powerful stimulus of individual, social, and political progress.” But even if we take the ground, that education and suffrage, though not actually, should properly be, identical, the argument would not apply to the case of the freedmen. What we need primarily at the South is loyal citizens of the United States, and treason there is in inverse proportion to ignorance. If, in reconstructing the Rebel communities, we make suffrage depend on education, we inevitably put the local governments into the hands of a small minority of prominent Confederates whom we have recently defeated; of men physically subdued, but morally rebellious; of men who have used their education simply to destroy the prosperity created by the industry of the ignorant and enslaved, and who, however skilful they may be as “architects of ruin,” have shown no capacity for the nobler art which repairs and rebuilds. If, on the other hand, we make suffrage depend on color, we disfranchise the only portion of the population on whose allegiance we can thoroughly rely, and give the States over to white ignorance and idleness led by white intrigue and disloyalty. We are placed by events in that strange condition in which the safety of that “republican form of government” we desire to insure the Southern States has more safeguards in the instincts of the ignorant than in the intelligence of the educated. The right of the freedmen, not merely to the common privileges of citizens, but to own themselves, depends on the connection of the States in which they live with the United States being preserved. They must know that Secession and State Independence mean their reënslavement. Saulsbury of Delaware, and Willey of West Virginia, declared in the Senate, in 1862, that the Rebel States, when they came back into the Union, would have the legal power to reënslave any blacks whom the National government might emancipate; and it is only the plighted faith of the United States to the freedmen, which such a proceeding would violate, which can prevent the crime from being perpetrated. It is as citizens of the United States, and not as inhabitants of North Carolina or Mississippi, that their freedom is secure. Their instincts, their interests, and their position will thus be their teachers in the duties of citizenship. They are as sure to vote in accordance with the most advanced ideas of the time as most of the embittered aristocracy are to vote for the most retrograde. They will, though at first ignorant, necessarily be in political sympathy with the most educated voters of New York, Ohio, and Massachusetts; if they were as low in the scale of being as their bitterest revilers assert, they would still be forced by their instincts into intuitions of their interests; and their interests are identical with those of civilization and progress. We suppose that those who think them most degraded would be willing to concede to them the possession of a little selfish cunning; and a little selfish cunning is enough to bring them into harmony with the purposes, if not the spirit, of the largest-minded philanthropy and statesmanship of the North.

It is claimed, we know, by some of the hardiest dealers in assertion, that the freedmen will vote as their former masters shall direct; but as this argument is generally put forward by those whose sympathies are with the former masters rather than with the emancipated bondmen, one finds it difficult to understand why they should object to a policy which will increase the power of those whom they wish to be dominant. …

We think, then, it may be taken for granted, that, while ignorant, the freedmen will vote right by the force of their instincts, and that the education they require will be the result of their possessing the political power to demand it. Free schools are not the creations of private benevolence, but of public taxation; it is useless to expect a system of universal education in a community which does not rest on universal suffrage; and the children of the poor freeman are educated at the public expense, not so much by the pleading of the children’s needs as by the power of the father’s ballot. To take the ground, that the “superior” race will educate the “inferior” race it has but just held in bondage, that it will humanely set to work to prepare and qualify the “niggers” to be voters, only escapes from being considered the artifice of the knave by charitably referring it to the credulity of the simpleton. We do not send, as Mr. Sumner has happily said, “the child to be nursed by the wolf”; and he might have added, that the only precedent for such a proceeding, the case of Romulus and Remus, has lost all the little force it may once have had by the criticism of Niebuhr.

If the negroes do not get the power of political self-protection in the conventions of the people which are now to be called, it is not reasonable to expect they will ever get it by the consent of the whites. … For, disguise it as we may, the United States government really holds and exercises the power which gives vitality to the preliminaries of reconstruction, and it is therefore responsible for all evils in the future which shall spring from its neglect or injustice in the present.

The addition, too, of four millions of persons to the people of the South, without any corresponding addition of voters, will increase the political power of the ruling whites to an alarming extent, while it will remove all checks on its mischievous exercise. The constitution declares that “representatives and direct taxes shall be apportioned among the several States, which may be included in this Union, according to their respective numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole number of free persons, including those bound to service for a term of years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other persons.” The unanswerable argument presented at the time against the clause relating to the slaves did not prevent its adoption. “If,” it was said, “the negroes are property, why is other property not represented? if men, why three fifths?” Still the South has always enjoyed the double privilege of treating the negro as an article of merchandise and of using three fifths of him as political capital. He has thus added to the power by which he was enslaved, and has been represented in Congress by persons who regarded him either as a beast or as “a descendant of Ham.” In 1860, when the ratio of representation was about one hundred and twenty-seven thousand, the South had, by the three-fifths rule, the right to eighteen more representatives in Congress, and eighteen more electoral votes, than it would have had, if only free persons had been counted. The emancipation of the slaves will give it twelve more; for the blacks will now no longer be constitutional fractions, but constitutional units. The three-fifths arrangement was a monstrous anomaly; but the five-fifths will be worse, if negro suffrage be denied. Four millions of free people will, by the mere fact of being inhabitants of Southern territory, confer a political power equal to thirty members of Congress, and yet have no voice in their election. It has been computed by the Hon. Robert Dale Owen, in a paper on the subject, published in the New York “Tribune,” that in some States, where the blacks and whites are about equal in number, and where two thirds of the whites shall “qualify” as voters, this new condition of things will give the Southern white voter, in a Presidential or Congressional election, three times as much political influence as a Northern voter. …

But this great power, wielded by a population imperfectly qualified to vote, in the name of a population which do not vote at all,—a power equivalent to thirty members of Congress and thirty electoral votes,—will be directed as much against Northern interests as against negro interests. …

One result of Southern predominance everybody can appreciate. The national debt is so interwoven with every form of the business and industry of the loyal States that its repudiation would be the most appalling of evils. A tax to pay it at once would not produce half the financial derangement and moral disorder which repudiation would cause; for repudiation, as Mirabeau well observed, is nothing but taxation in its most cruel, unequal, iniquitous, and calamitous form. But what reason have we to think that a reconstructed South, dominant in the Federal government, would regard the debt with feelings similar to ours? The negroes would associate it with their freedom, of which it was the price; their late masters would view it as the symbol of their humiliation, which it was incurred to effect. …

From every point of view, then, in which we can survey the subject, negro suffrage is, unless we are destitute of the commonest practical reason, the logical sequence of negro emancipation. It is not more necessary for the protection of the freedmen than for the safety and honor of the nation. Our interests are inextricably bound up with their rights. The highest requirements of abstract justice coincide with the lowest requirements of political prudence. And the largest justice to the loyal blacks is the real condition of the widest clemency to the Rebel whites. If the Southern communities are to be reorganized into Federal States, it is of the first importance that they should be States whose power rests on the proscription or degradation of no class of their population. It would be a great evil, if they were absolutely governed by a faction, even if that faction were a minority of the “loyal” people, whose loyalty consisted in merely taking an oath which the most unscrupulous would be the readiest to take, because the readiest to break. We are bound either to give them a republican form of government, or to hold them in the grasp of the military power of the nation; and we cannot safely give them anything which approaches a republican form of government, unless we allow the great mass of the free people the right to vote. And least of all should we think of proscribing that particular class of the free people who most thoroughly represent in their localities the interests of the United States, and whose ballots would at once do the work and save the expense of an army of occupation.

_____________________________________________________________________

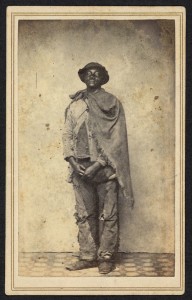

This image of the side-by-side New Jersey state platforms from 150 years ago this month have a couple planks about slavery and voting rights. The Republicans didn’t specifically mention black suffrage; the Democrats were opposed. You can find it at the Library of CongressThe Republicans: “pledge the unanimous support of the Union men of New Jersey to the constitutional amendment abolishing slavery, and we feel deeply humiliated by the position of our State as the only free State which has refused to ratify that amendment; [even many rebels acknowledge the necessity of freeing the slaves, but New Jersey Democrats] still strives against the spirit of the age, the conscience of the people and the irresistible tendencies of freedom, by thwarting a policy plainly essential to the future security and welfare of the nation.” The next Republican plank puts new emphasis on the words of the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal,” and governments were set up to secure the principles of the Declaration.

The Democrats resolved “that we are most emphatically opposed to negro suffrage, and entirely agree with President Johnson, that the people of each State have the right to control that subject as they deem best.”

![NJ Platforms 1865 (The two platforms. Look on this picture. Union platform, adopted at Trenton, July 20, 1865. And then on this! Democratic platform, adopted at Trenton, August 30, 1865. Jersey City. From the Times" Printing House, 43 Montgomery Street [1865].; LOC: http://www.loc.gov/item/rbpe.10004200/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/NJ-Platforms-1865-218x300.jpg)