During the 1866 campaign season a “radical convention” met in Philadelphia from September 3-7. Southern “loyalists” participated; it seems they were loyal to Congress and the radical Republican approach to Reconstruction. Here is Charles Ernest Chadsey’s 1896 take on President Johnson’s “Swing Around the Circle” followed by his explanation of the Philadelphia radical convention. From The Struggle between President Johnson and Congress over Reconstruction (pages 95-100):

But his indiscretions did not end with speeches before his sympathizers. Two weeks later he started on a trip, nominally to assist in the ceremony of laying the cornerstone of the Douglas monument in Chicago. As a matter of fact, however, he was merely taking advantage of an opportunity to defend his policy publicly. Johnson was of too impassioned a nature to be able to judge as to how far the President of the United States could afford to adopt the methods of the stump speaker. All constraint was thrown away, and he acted at many times the part most natural to him, that of a popular orator addressing the masses. His speeches at no time lacked clearness. All could see where he stood, and nothing was left for speculation.

His first important effort while on his journey was at New York on August 29, where he responded to a toast proposed by the mayor of the city. In this speech he defined the issue as follows: “The rebellion has been suppressed, and in the suppression of the rebellion it [the government] has * * * established the great fact that these States have not the power, and it denied their right, by forcible or peaceable means, to separate themselves from the Union. (Cheers, ‘Good!’) That having been determined and settled by the Government of the United States in the field and in one of the departments of the government—the executive department of the government—there is an open issue; there is another department of your government which has declared by its official acts, and by the position of the Government, notwithstanding the rebellion was suppressed for the purpose of preserving the Union of the States and establishing the doctrine that the States could not secede, yet they have practically assumed and declared and carried up to the present point, that the Government was dissolved and the States were out of the Union. (Cheers.) We who contended for the opposite doctrine years ago contended that even the States had not the right to peaceably secede; and one of the means and modes of possible secession was that the States of the Union might withdraw their representatives from the Congress of the United States, and that would be practical dissolution. We denied that they had any such right. (Cheers.) And now, when the doctrine is established that they have no right to withdraw, and the rebellion is at an end * * * we find that in violation of the Constitution, in express terms as well as in spirit, that these States of the Union have been and still are denied their representation in the Senate and in the House of Representatives.” Then, speaking of the people of the South: “* * Do we want to humiliate them and degrade them and drag them in the dust? (‘No, no!’ Cheers.) I say this, and I repeat it here to-night, I do not want them to come back to this Union a degraded and debased people. (Loud cheers.) They are not fit to be a part of this great American family if they are degraded and treated with ignominy and contempt. I want them when they come back to become a part of this great country, an honored portion of the American people.”

Another representative speech was the one which he made in Cleveland on September 3: “I tell you, my countrymen, I have been fighting the South, and they have been whipped and crushed, and they acknowledge their defeat and accept the terms of the Constitution; and now, as I go around the circle, having fought traitors at the South, I am prepared to fight traitors at the North. (Cheers.) God willing, with your help we will do it. (Cries of ‘We won’t.’) It will be crushed North and South, and this glorious Union of ours will be preserved. (Cheers.) I do not come here as the Chief Magistrate of twenty-five States out of thirty-six. (Cheers.) I came here to-night with the flag of my country and the Constitution of thirty-six States untarnished. Are you for dividing this country? (Cries of ‘No.’) Then I am President, and I am President of the whole United States. (Cheers.)”

Speeches of this nature, coming at a time when the outrages in the South had so greatly incensed the North, had a most depressing influence upon the fortunes of the National Union party, and failed utterly in the object for which they were intended. The trip proved to be a grave political mistake. The undignified spectacle of a President receiving coarse personal abuse and retorting in scarcely less coarse expressions was quickly taken advantage of by his opponents; and the phrase “swinging around the circle” has assumed historic dignity as a description of his journey.

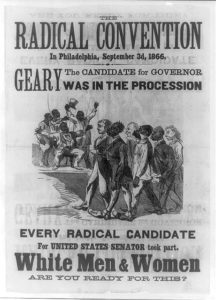

4. The “off year” national convention plan adopted by the National Union Club was immediately accepted by the congressional party, which was no less active in preparations for the struggle. On July 4, the same day on which the Democratic congressmen issued their address to the people, representative Southern Unionists, supporters of Congress, issued a call to “the Loyal Unionists of the South,” for a convention to be held in Philadelphia on September 3. The call stated that the convention was “for the purpose of bringing the loyal Unionists of the South” into conjunction with the true friends of republican government in the North. “* * The time has come when the restructure of Southern State government must be laid on constitutional principles. * * * We maintain that no State, either by its organic law or legislation, can make transgression on the rights of the citizen legitimate. * * * Under the doctrine of ‘State sovereignty,’ with rebels in the foreground, controlling Southern legislatures, and embittered by disappointment in their schemes to destroy the Union, there will be no safety for the loyal element of the South. Our reliance for protection is now on Congress, and the great Union party that has stood and is standing by our nationality, by the constitutional rights of the citizen, and by the beneficent principles of the government.”

The convention met at the time appointed, with representatives present from all the lately insurrectionary States. James Speed of Kentucky, Attorney-General until July 18, was elected permanent chairman. For purposes of co-operation, the Northern States had been invited to send delegations, and all responded. Thus the convention was as truly national as the “National Union” convention of August 14 had been. It was decided, however, that for the purpose of rendering the declaration of the Southern Unionists more significant, the Northern and Southern Unionists should hold their sessions separately, and Governor Curtin of Pennsylvania was accordingly elected chairman of the Northern section.

The resolutions of the Southern section were reported by Governor Hamilton of Texas, chairman of the committee on resolutions, and they naturally endorsed the action of Congress in its entirety. While demanding the restoration of the States, they declared Johnson’s policy to be “unjust, oppressive, and intolerable,” and that restoration under his “inadequate conditions” would only magnify “the perils and sorrows of our condition.” They agreed to support Congress and to endeavor to secure the ratification of the 14th Amendment. Congress alone had power to determine the political status of the States and the rights of the people, “to the exclusion of the independent action of any and every other department of the Government.” “The organizations of the unrepresented States, assuming to be state governments, not having been legally established,” were declared “not legitimate governments until reorganized by Congress.” In addition to these resolutions, an address “from the loyal men of the South to their fellow-citizens of the United States,” was prepared and adopted after the formal adjournment of the convention. This reaffirmed, in far stronger terms, the condemnation of President Johnson, specifying many ways in which he had wrought injury to them, and closing with the following significant and powerful declaration: “We affirm that the loyalists of the South look to Congress with affectionate gratitude and confidence, as the only means to save us from persecution, exile and death itself; and we also declare that there can be no security for us or our children, there can be no safety for the country against the fell spirit of slavery, now organized in the form of serfdom, unless the Government, by national and appropriate legislation, enforced by national authority, shall confer on every citizen in the States we represent the American birthright of impartial suffrage and equality before the law. This is the one all-sufficient remedy. This is our great need and pressing necessity.”

It has been reported that at 4:20 PM 150 years ago today President Johnson and entourage arrived in Springfield, Illinois, where Democrats did their best to extend a cordial greeting and Republicans did their best to snub the president but welcome his traveling companions.