April 14, 1865 was something of a banner day in Washington, D.C. Gilbert Bates, who had served as a sergeant in the 1st Wisconsin Heavy Artillery during the war, arrived on foot in the nation’s capital carrying the Stars and Stripes. Sergeant Bates wagered with a neighbor in Wisconsin that he could safely walk through the South with the national flag in full display. He left Vicksburg on January 28th and, although Mark Twain reportedly wrote that he would show up in D.C. pretty much maimed, Sergeant Bates arrived in one piece 150 years ago today, after having walked about 1400 miles through six Southern states with the flag unfurled. He had won his bet, but a Northern periodical was unimpressed.

From the May 2, 1868 issue of Harper’s Weekly (page 276) (at the Internet Archive):

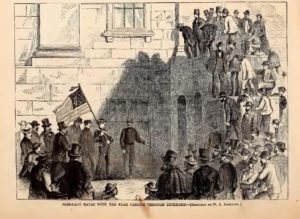

SERGEANT BATES’S PILGRIMAGE.

SERGEANT GILBERT H. BATES, who was formerly a soldier in a Wisconsin regiment, partly in emulation of WESTON, but principally because he seems to have had nothing better to do, lately made a wager that he would walk in 78 days from Vicksburg to Washington city, carrying the United States flag, and depending entirely on the hospitality of the people of the South for support. The wager has been won. Sergeant BATES triumphantly ended his pilgrimage on April 14. There is no reason why he should not have won the wager if he had any endurance as a pedestrian. The distance is not great; the flag is not heavy; and it has been carried as triumphantly through the same region against greater obstacles than Sergeant BATES appears to have encountered.

The people of the South have made use of the incident to display their enthusiasm and patriotism; but, if we are to credit the story of the Sergeant, the demonstrations seem to have been confined almost exclusively to praises of course of President JOHNSON and to prayers for their rights.

Our illustration represents the Sergeant passing through Richmond, Virginia. He was received there with much enthusiasm – how genuine it is difficult to determine. The exhibition of loyalty on the part of the Southern people is desirable under any and all circumstances, but their demonstrations in this instance have evidently been the result of a little exuberance of feeling at the presence of this man. We can not forget that WESTON created just as much excitement on a trip of the same nature. And, moreover, it cannot but be remembered that, while this stranger was not molested or interrupted on his way, peaceable and worthy men of undoubted and undaunted loyalty, living at the South, were foully and cruelly murdered for their sentiments.

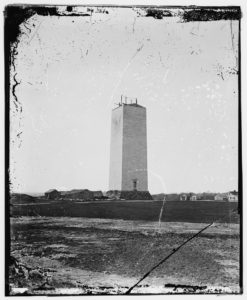

Sergeant Bates wrote a pamphlet describing his walk (at Hathi Trust). The whites were mostly kind; many blacks seemed to be very idle, possibly because the Freedmen’s Bureau fed them when necessary. He was only attacked by a bunch of dogs but used his flagstaff to fend them off. Sergeant Bates felt threatened by a group of blacks in Augusta but believed unscrupulous whites had put them up to it. A crowd of hundreds cheered him when he arrived in Washington on the 14th; he was welcomed by a Committee from the Conservative Army and Navy Union and later by a Committee of the Citizens of Washington. A procession with band escorted him to the White House; President Johnson didn’t have a speech to make but wanted to welcome the marcher and his flag. Speeches were delivered at the Metropolitan Hotel. Reportedly on orders of some Radical Republican members of Congress, a policeman refused to allow Sergeant Bates to enter the Capitol with his flag and fly it from the dome. Rebuffed by Congress, the sergeant marched to the uncompleted Washington Monument, where E.O. Perrin delivered a speech critical of Northern radicals: “that reckless Congress that squanders millions of the people’s money on Freedmen’s Bureaus and sable cemeteries, but cannot spare a dollar to the memory of George Washington, whose sacred ashes slumber to-day “in a conquered province” outside of the Union he created and loved so well, and in sight of the very Capitol that bears his honored name.”

At the end of the pamphlet Sergeant Bates summarized his findings – Southerners (white) loved their country and its flag but did not want to be governed by negroes.

Your article wrongly refers to Edward Payson Weston as ‘Mr. Payson’…

It is, in fact, ‘Mr. Weston’…

Thank you very much for pointing that out. I will make the changes