On November 6, 1917 New York State voters approved an amendment to the state constitution that allowed women the right to vote in all elections in the state. A large New York City majority in favor of the amendment offset a slightly negative vote in the rest of the state. Of course, for one last election in New York, all the voters were men.

________________________________________

New York State women had always been leaders of the long struggle for female suffrage:

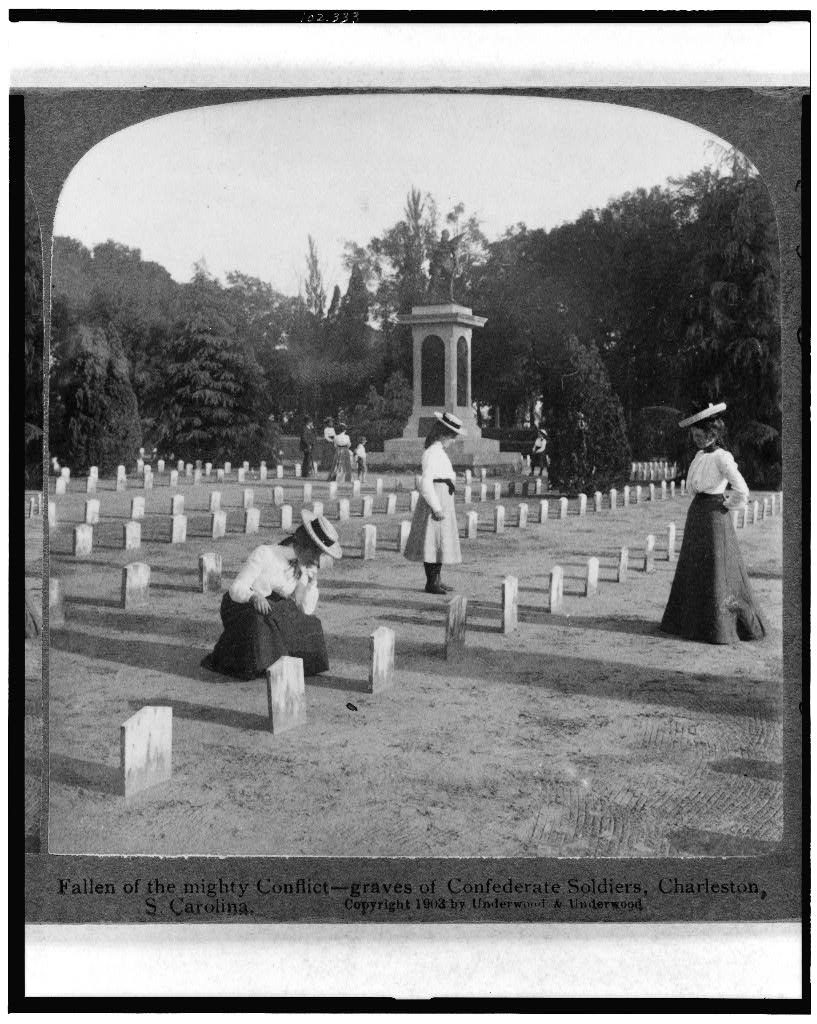

In the period following the Civil War, the various national organizations demanding the vote for women drew their most enthusiastic support and most of their funds from New York. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony were in this period the acknowledged leaders of the movement in both the state and the nation. … [Women waged a persistent and protracted campaign that involved lobbying, meetings, speeches, propaganda, and pestering] … “At the state constitutional conventions of 1867 and 1894, they unsuccessfully sought an amendment granting women the right to vote” …

[The work continued] … Although Miss Stanton died in 1902 and Miss Anthony in 1906, there were now many others to carry on their work, and Miss Carrie Chapman Catt emerged as the generally acknowledged leader of the movement in both the state and the country.

By 1910 the suffragettes were committed to an aggressive campaign that was as spectacular as it was effective. The old methods were not abandoned, but many new ones were added. Suffragette societies were organized along the lines of political parties; huge parades were held in New York City; motorcades toured the state distributing literature; street-corner speakers urging the vote for women became a commonplace in large cities; a one-day strike of women was threatened; and almost any stunt that would attract publicity was used. These tactics and the long campaign of education that had been carried on by earlier suffragettes finally produced results. A bill for amending the state constitution was passed by the legislature in 1913 and repassed in 1915, but was rejected by the voters at the polls. The process was immediately repeated, and this time it proved successful. The legislature passed the bill in 1916 and 1917, and the voters approved it in the fall of 1917. …[1]You can read a good article about the history of the 1917 New York constitutional amendment by Susan Ingalls Lewis at SUNY New Paltz.

____________________________________

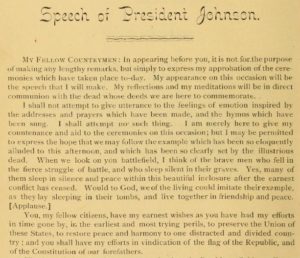

Here’s a little about how nascent suffragettes remembered the 1867 New York State constitutional convention. From History of Woman Suffrage, Volume II, edited by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage (1881; pages 269-270):

NEW YORK CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION.

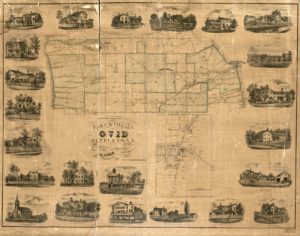

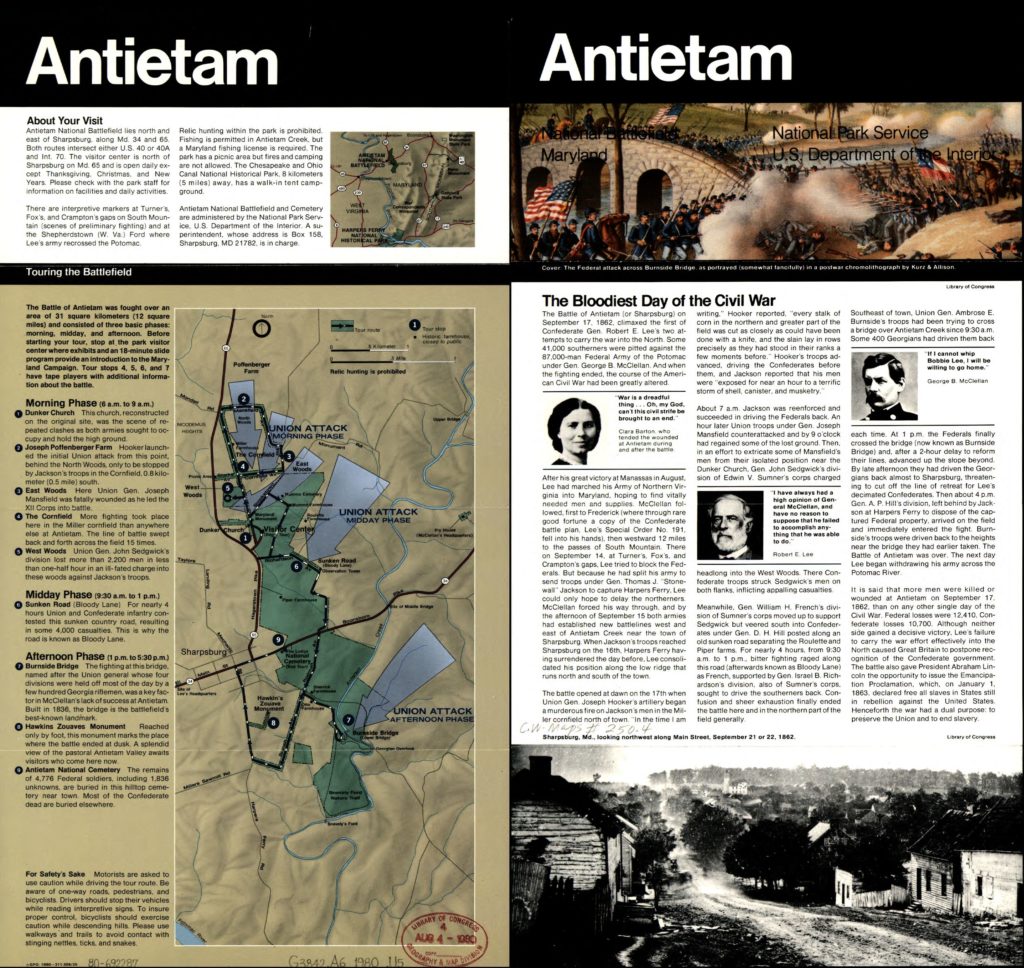

Constitution Amended once in Twenty Years—Mrs. Stanton Before the Legislature Claiming Woman’s Right to Vote for Members to the Convention—An Immense Audience in the Capitol—The Convention Assembled June 4th, 1867. Twenty Thousand Petitions Presented for Striking the Word “Male” from the Constitution—”Committee on the Right of Suffrage, and the Qualifications for Holding Office.” Horace Greeley, Chairman—Mr. Graves, of Herkimer, Leads the Debate in favor of Woman Suffrage—Horace Greeley’s Adverse Report—Leading Advocates Heard before the Convention—Speech of George William Curtis on Striking the Word “Man” from Section 1, Article 11—Final Vote, 19 For, 125 Against—Equal Rights Anniversary of 1868.

This was the first time in the history of the woman suffrage movement that the Constitution of New York was to be amended, and the general interest felt by women in the coming convention was intensified by the fact that such an opportunity for their enfranchisement would not come again in twenty years. The proposition of the republican party to strike the word “white” from the Constitution and thus extend the right of suffrage to all classes of male citizens, placing the men of the State, black and white, foreign and native, ignorant and educated, vicious and virtuous, all alike, above woman’s head, gave her a keener sense of her abasement than she had ever felt before. But having neither press nor pulpit to advocate her cause, and fully believing this amendment would pass as a party measure, she used every means within her power to arouse and strengthen the agitation, in the face of the most determined opposition of friends and foes. Meetings were held in all the chief towns and cities in the State, and appeals and petitions scattered in every school district; these were so many reminders to the women everywhere that they too had some interest in the Constitution under which they lived, some duties to perform in deciding the future policy of the Government.

This campaign cost us the friendship of Horace Greeley and the support of the New York Tribune, heretofore our most powerful and faithful allies. In an earnest conversation with Mrs. Stanton and Miss Anthony, Mr. Greeley said: “This is a critical period for the Republican party and the life of the Nation. The word “white” in our Constitution at this hour has a significance which “male” has not. It would be wise and magnanimous in you to hold your claims, though just and imperative, I grant, in abeyance until the negro is safe beyond peradventure, and your turn will come next. I conjure you to remember that this is “the negro’s hour,” and your first duty now is to go through the State and plead his claims.” “Suppose,” we replied, “Horace Greeley, Henry J. Raymond and James Gordon Bennett were disfranchised; what would be thought of them, if before audiences and in leading editorials they pressed the claims of Sambo, Patrick, Hans and Yung Fung to the ballot, to be lifted above their own heads? With their intelligence, education, knowledge of the science of government, and keen appreciation of the dangers of the hour, would it not be treasonable, rather than magnanimous, for them, leaders of the metropolitan press, to give the ignorant and unskilled a power in government they did not possess themselves? To do this would be to place on board the ship of State officers and crew who knew nothing of chart or compass, of the safe pathway across the sea, and bid those who understand the laws of navigation to stand aside. No, no, this is the hour to press woman’s claims; we have stood with the black man in the Constitution over half a century, and it is fitting now that the constitutional door is open that we should enter with him into the political kingdom of equality. Through all these years he has been the only decent compeer we have had. Enfranchise him, and we are left outside with lunatics, idiots and criminals for another twenty years.” “Well,” said Mr. Greeley, “if you persevere in your present plan, you need depend on no further help from me or the Tribune.” And he kept his word. We have seen the negro enfranchised, and twenty long years pass away since the war, and still woman’s turn has not yet come; her rights as a citizen of the United States are still unrecognized, the oft-repeated pledges of leading Republicans and Abolitionists have not been redeemed.

Mrs. Stanton might not have helped her friendship with Horace Greeley with a letter republished in the July 4, 1867 issue of The New-York Times. I think the state constitutional convention was also debating removing the property qualification for black men to vote. According to The New York History Blog that didn’t happen until the 15th amendment to the U.S. Constitution. From the suffrage history above and looking through NY Times headlines – Stanton and Anthony also campaigned for female suffrage in Kansas in 1867. In November 1867 Kansas voters rejected both negro and female suffrage.

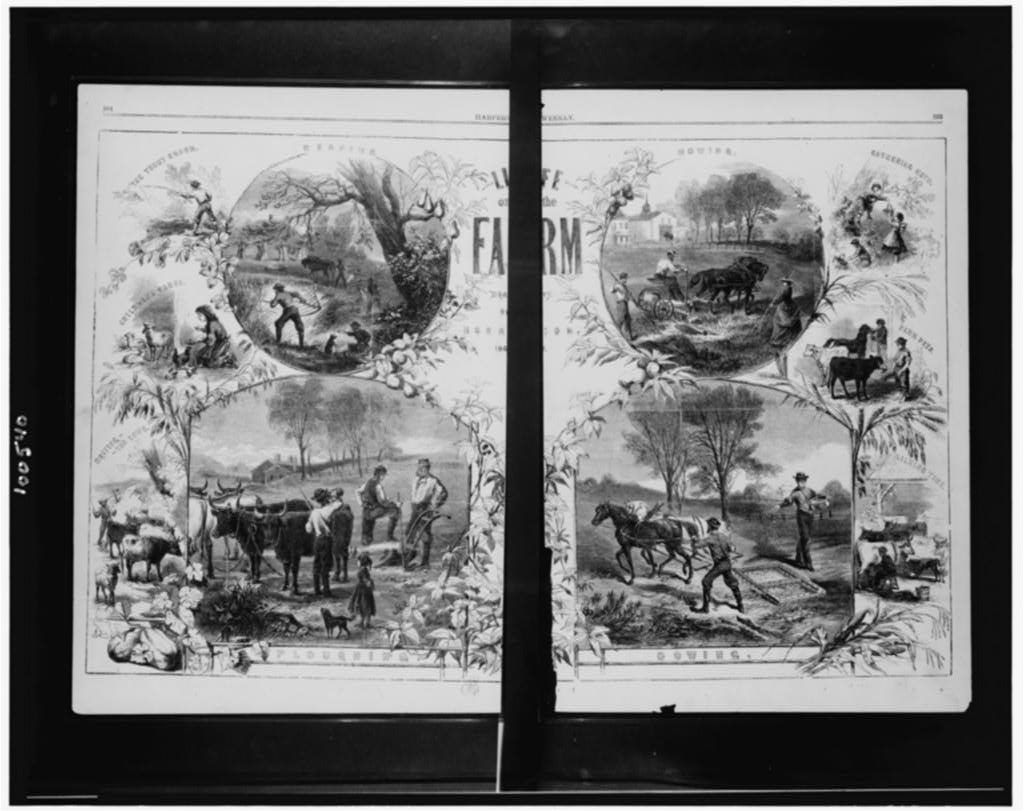

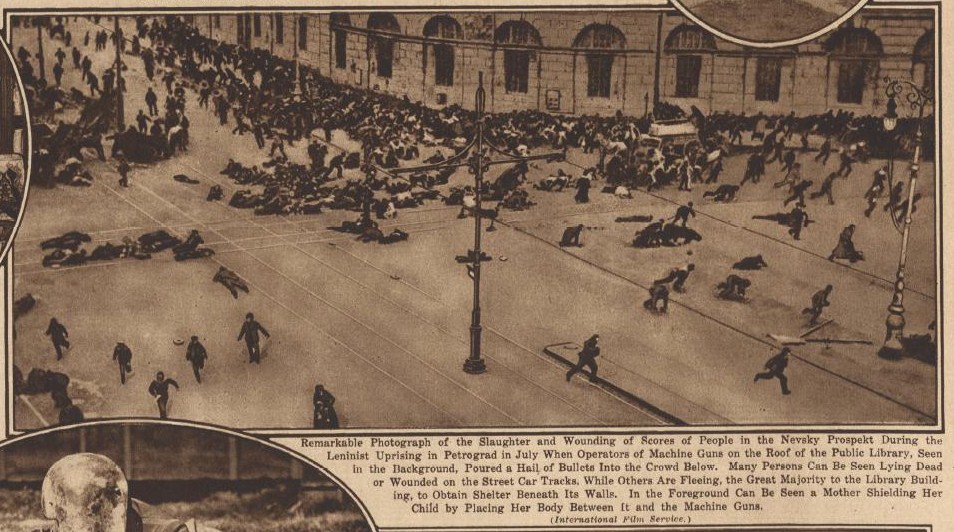

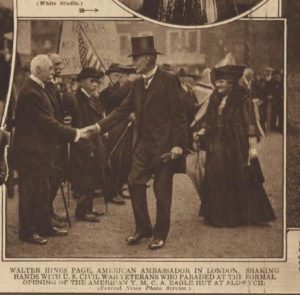

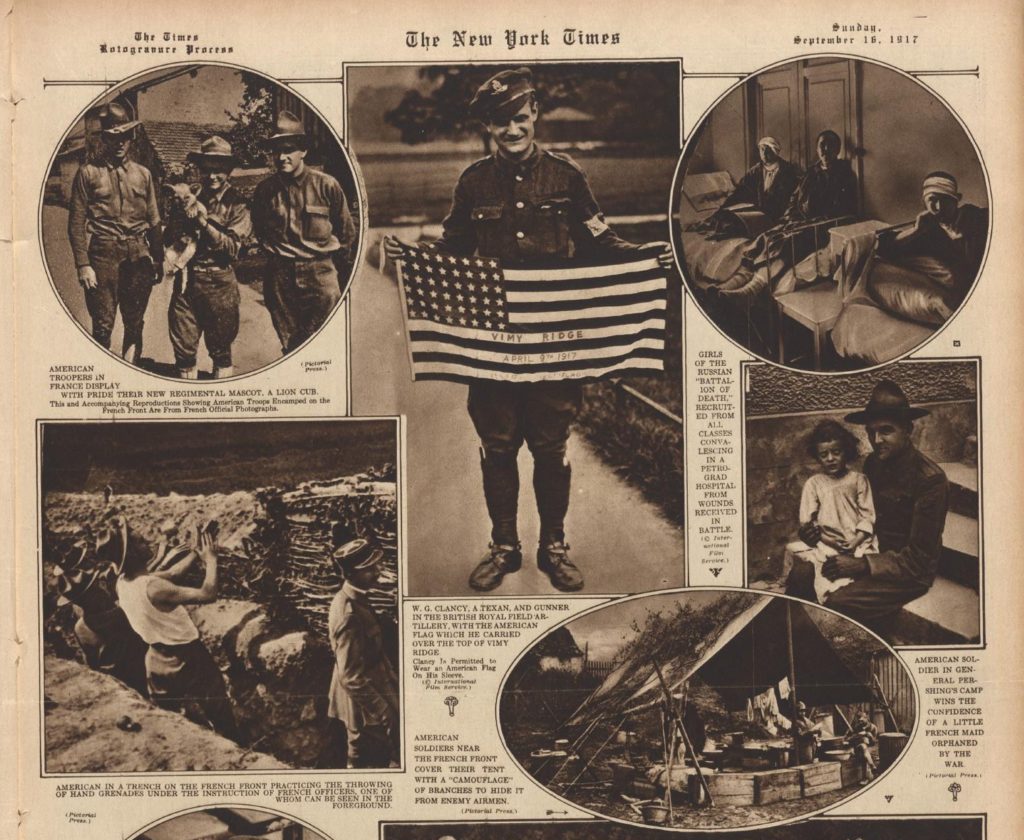

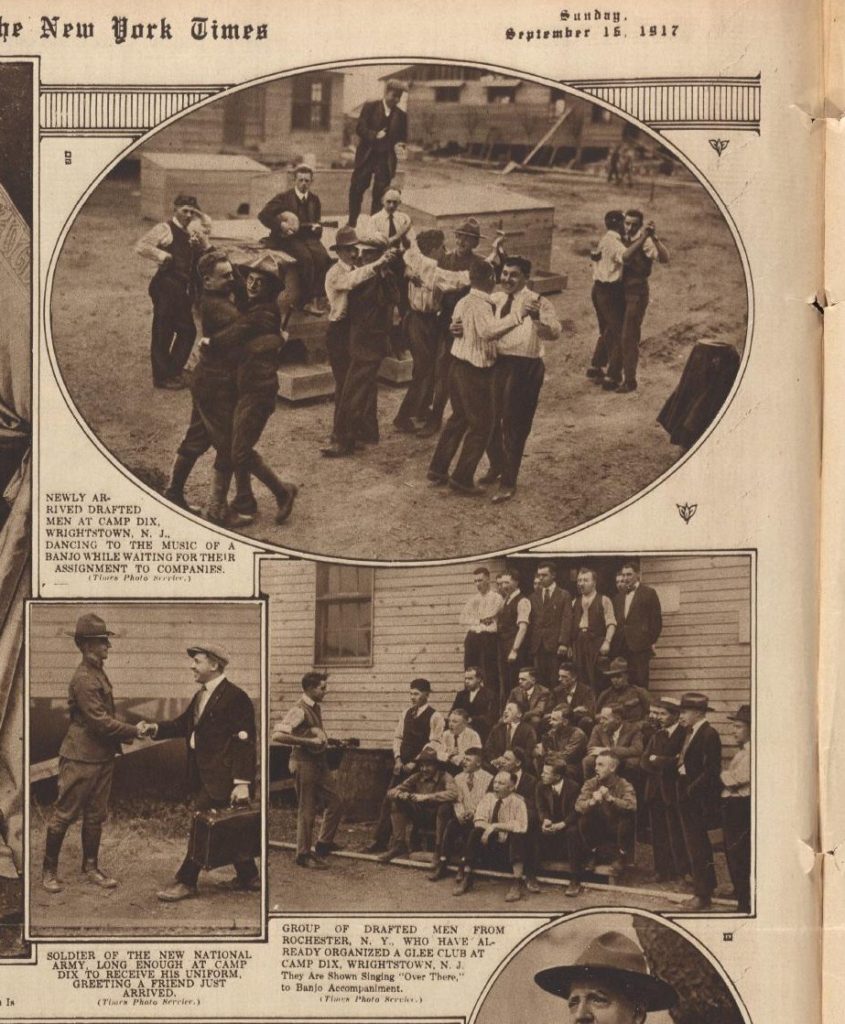

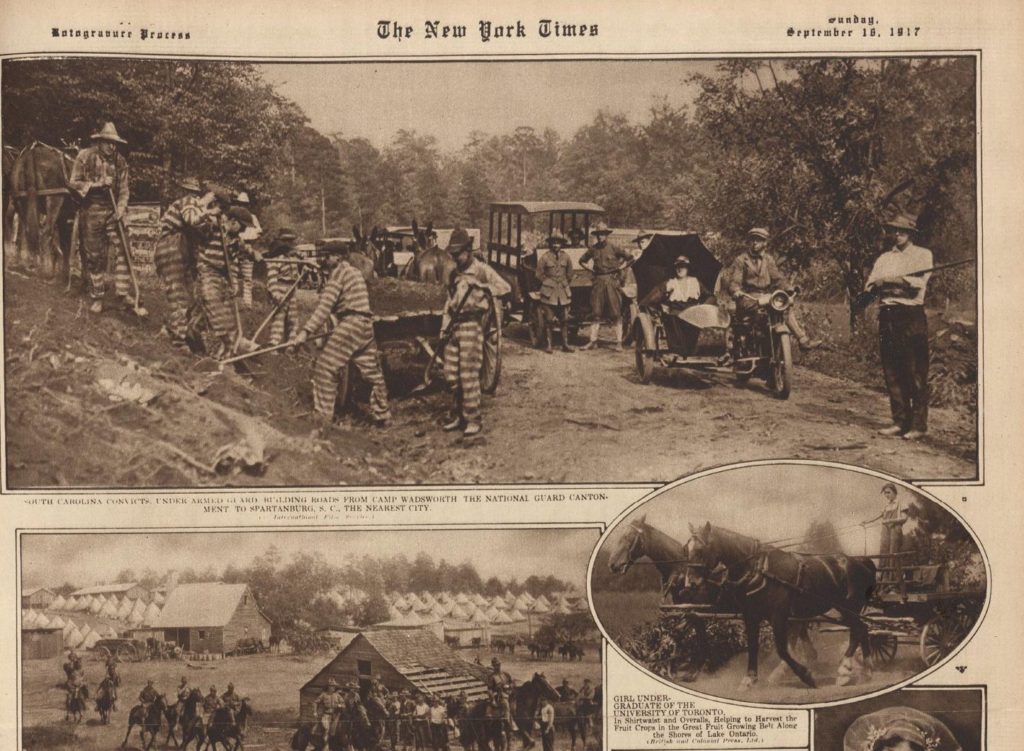

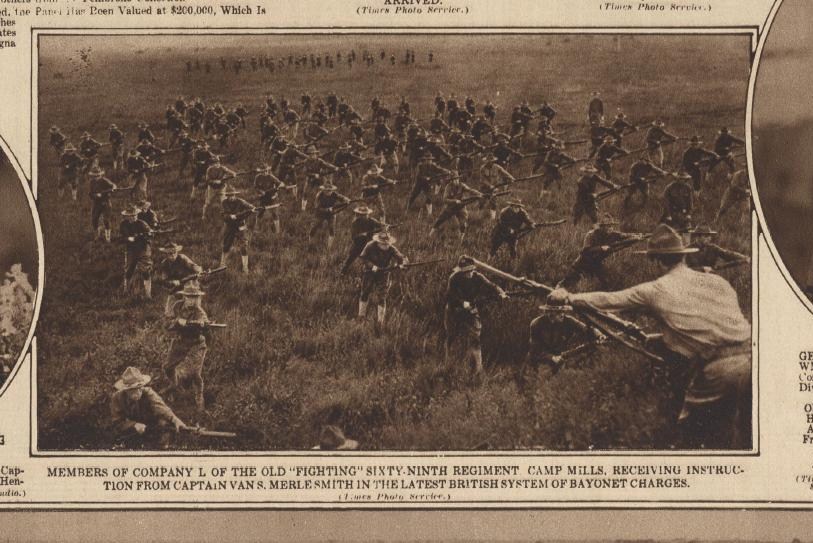

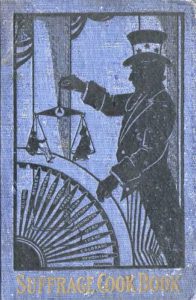

You can see the cover and read The Suffrage Cook Book at Project Gutenberg (Jack London and wife participated – check out their Liver Dumplings). From the Library of Congress: map from The Woman suffrage year book printed in January 1917; Carrie Chapman Catt; farmers; all the images from the photo section of the November 4, 1917 issue of The New-York Times; Susan B. Anthony(apparently Anthony signed the photo about a month before her death); Justice portrayed in Seneca Falls, New York in July 1923 to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the first women’s rights convention

- [1]Ellis, David M., James A. Frost, Harold C. Syrett, and Harry J. Carman. A Short History of New York State. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1957. Print. page 390-391.↩

![[Carrie Chapman Catt, half-length portrait, seated, facing left, on telephone] (between 1909 and 1932; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/94506343/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/3c10995v-246x300.jpg)