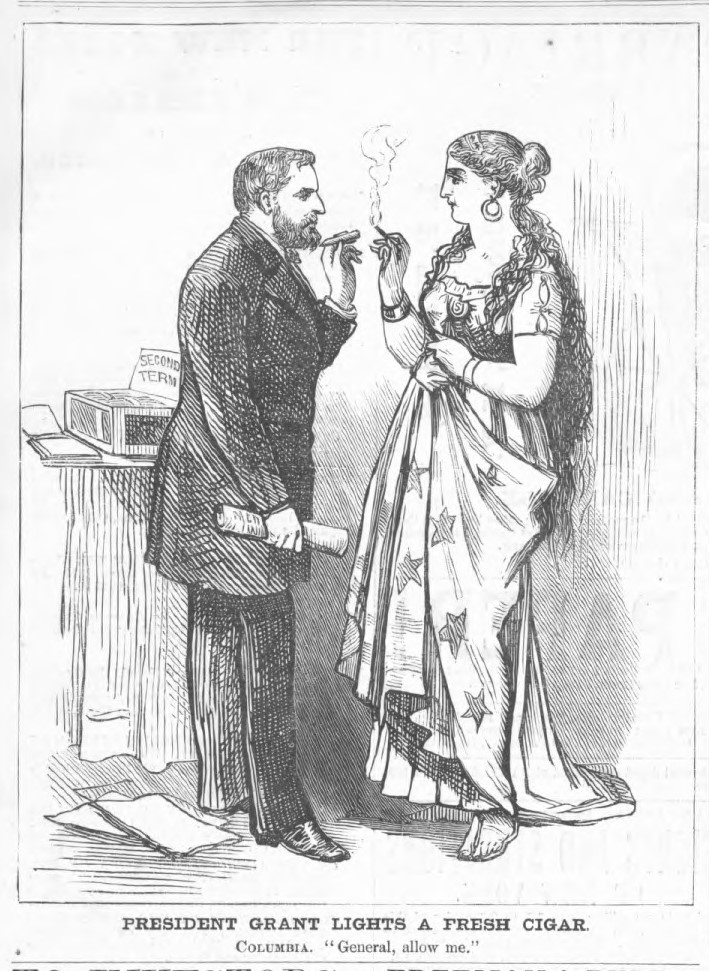

150 years ago this week people commemorated the centennial of the Boston Tea Party. According to the January 3, 1874 issue of Harper’s Weekly, one of the celebrations incorporated a contemporary political issue – women’s rights:

THE BOSTON TEA-PARTY.

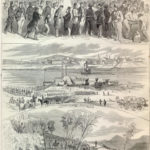

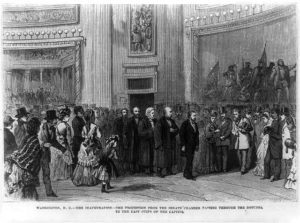

On the 15th of December a distinguished party of ladies and gentlemen assembled in Faneuil Hall to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of the famous Boston “Tea-Party,” when the cargoes of the Dartmouth, Eleanor, and Beaver, three British ships, consisting of 342 chests of tea, were thrown into the harbor by a body of sixty men disguised as Indians. The memorial party had also a semi-political aspect. It was originated and managed by Mrs. LUCY STONE in the interest of woman suffrage. Invitations were sent to many prominent agitators of woman’s rights, and, to the gratifications of the ladies who had the affair in charge, most of them were accepted. The celebration was a complete success, except in one respect – the supply of tea gave out before all the guests had been served. Colonel T. W. HIGGINSON presided, and to his judgment and general fitness for the position much of the success of the Centennial Tea-Party is to be attributed. Enthusiasm was not as prominent a feature of the celebration as its nature would lead one to suppose; the speeches were marked more by cool and solid argument than by stirring appeals to the feelings of the audience, and Lucy Stone’s address alone created any degree of enthusiasm. Every thing was carried out just as it was advertised, and the managers may well be proud of the success which attended their efforts.

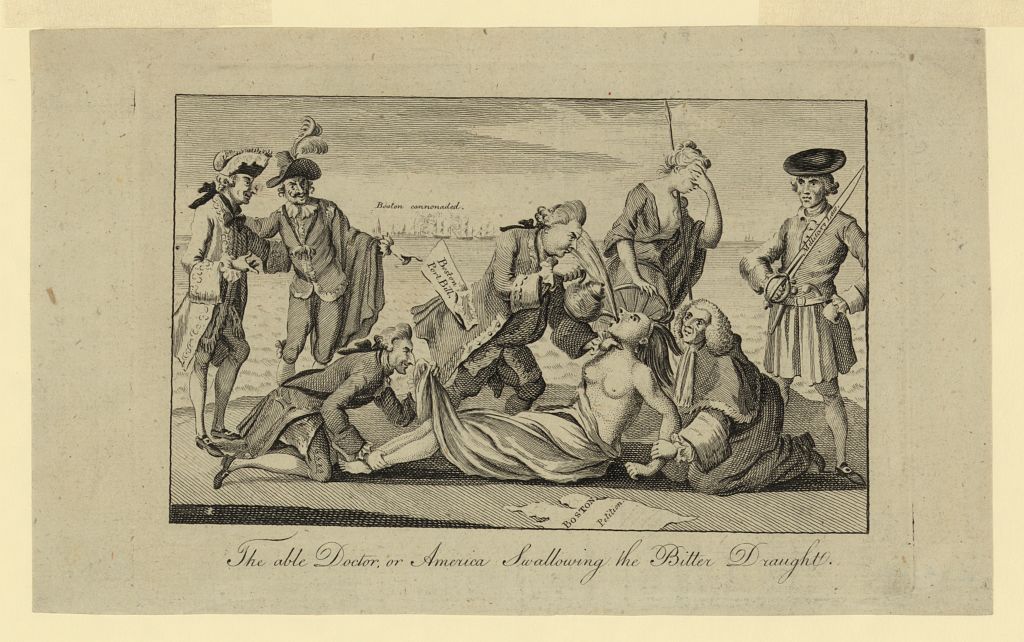

The original tea-party was a practical protest against the tea monopoly granted by the British government to the East India Company. A number of American merchants at that time in London were eager to secure the privilege of furnishing ships to carry the obnoxious cargoes to the colonies. But the sturdy colonists were determined to resist this encroachment on their rights. Great meetings were held in Boston and other cities to protest against the monopoly. The British government paid no heed to the popular demand, and regarded the agitation as a factious movement which would either die of itself or be easily crushed out by force.

Toward the end of November, 1773, the Dartmouth arrived at Boston, and came to anchor near the Castle. A meeting of the people of Boston and the neighboring towns was convened at Faneuil Hall, which being too small, the assembly adjourned to the Old South Meetinghouse. A resolution was adopted declaring that “the tea shall not be landed, that no duty shall be paid, and that it shall be sent back in the same bottom.” The people also voted “that Mr. Roch, the owner of the vessel, be directed not to enter the tea, at his peril, and that Captain HALL be informed, and at his peril, not to suffer any of the tea to be landed.” The ship was ordered to be moored at Griffin’s Wharf, and a guard of twenty-five men was appointed to watch her. The meeting received a letter from the consignees, offering to store the tea until instructions could be received from England, but the proposal was rejected. The sireriff [sic] then read a proclamation ordering the people to disperse. It was greeted with hisses.

By the 14th of December two other ships loaded with tea had arrived, and were moored at Griffin’s Wharf, under charge of the volunteer guard, and public order was well observed. Another meeting was held on the 14th in the Old South, when it was resolved to order Mr. Roch to apply immediately for a clearance for his ship, and send her to sea. The Governor meanwhile had taken measures to prevent her sailing out of the harbor. Two armed ships were stationed at the entrance, and the commandant of the Castle received orders not to allow any vessel to pass outward without a permit from the Governor.

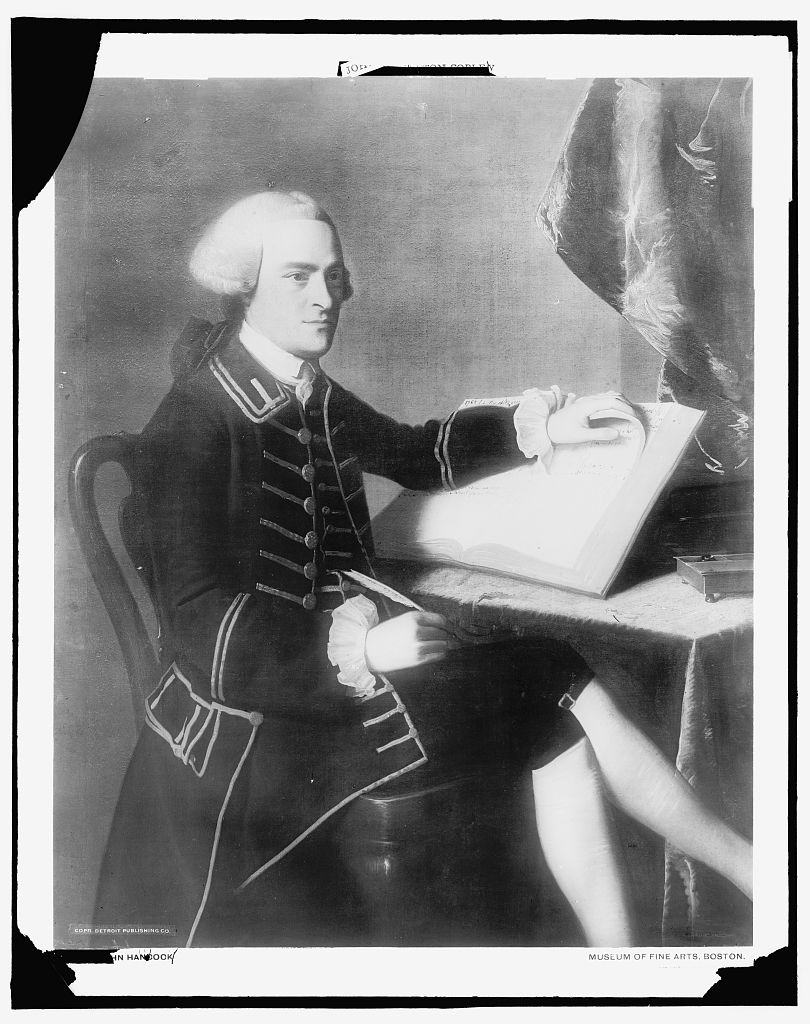

This roused the popular feeling to a white heat. On the 16th several thousand people met in the Old South and vicinity. SAMUEL PHILLIPS SAVAGE presided. The youthful JOSIAH QUINCY made a stirring speech, at the close of which (about three o’clock in the afternoon) the question was put, “Will you abide by your former resolutions with respect to not suffering the tea to be landed?” The vast assembly, as with one voice, gave an affirmative reply. Mr. ROCH in the mean while had been sent to the Governor, who was at his country-house at Milton, a few miles from Boston, to request a permit for his vessel to leave the harbor. A demand was also made upon the Collector for a clearance, but he refused until the tea should be landed. ROCH returned late in the afternoon with information that the Governor refused to grant a permit until a clearance should be exhibited. The meeting was greatly excited; and, as twilight was approaching, a call was made for candles. At that moment a person disguised like a Mohawk Indian raised the war-whoop in the gallery of the Old South, which was answered from without. Another voice in the gallery shouted, “Boston Harbor a tea-pot to-night! Hurra for Griffin’s Wharf!” A motion was instantly made to adjourn, and the people, in great confusion, crowded into the streets. Several persons in disguise were seen crossing Fort Hill in the direction of Griffin’s Wharf, and thitherward the populace pressed.

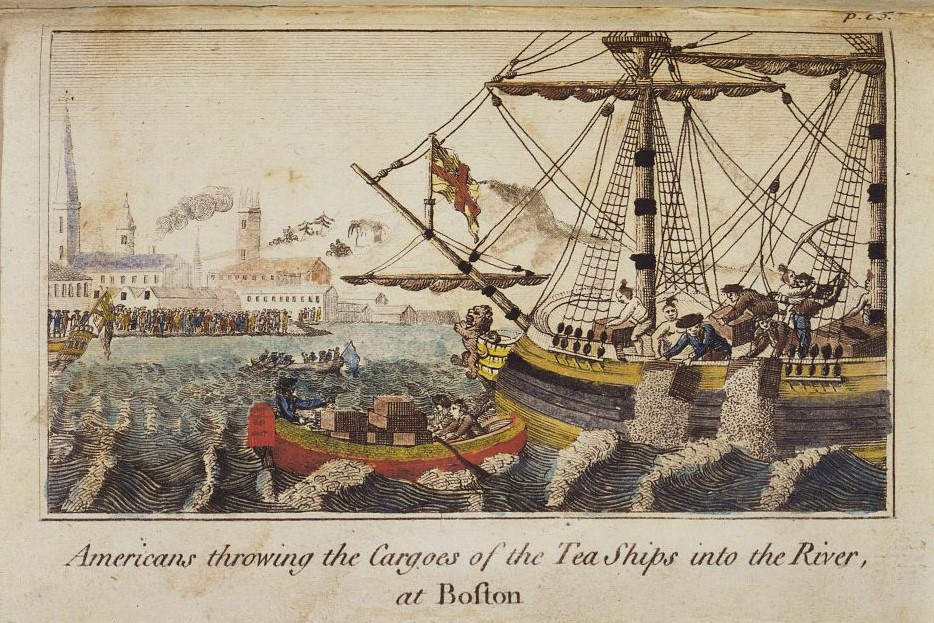

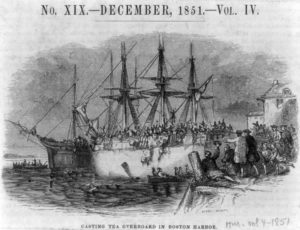

Concert of action marked the operations at the wharf; a general system of proceedings had doubtless been previously arranged. The number of persons disguised as Indians was fifteen or twenty, but about sixty went on board the vessels containing the tea. Before the work was over it was estimated that one hundred and forty were engaged. A man named LENDALL PITTS seems to have been recognized by the party as a sort of commander-in-chief, and under his directions the Dartmouth was first boarded, the hatches were taken up, and her cargo, consisting of one hundred and fourteen chests of tea, was brought on deck, where the boxes were broken open and their contents cast into the water. The other two vessels (the Eleanor, Captain JAMES BRUCE, and the Beaver, Captain HEZEKIAH COFFIN) were next boarded, and all the tea they contained was thrown into the harbor. The whole quantity thus destroyed within the space of two hours was three hundred and forty-two chests.

It was an early hour on a clear, moonlight evening when this transaction took place, and the British squadron was not more than a quarter of a mile distant. British troops, too, were near, yet the whole proceeding was uninterrupted. This apparent apathy on the part of government officers can be accounted for only by the fact, alluded to by the papers of the time, that something far more serious was expected on the occasion of an attempt to land the tea, and that the owners of the vessels, as well as the public authorities, felt themselves placed under lasting obligations to the rioters for extricating them from a serious dilemma. They certainly would have been worsted in an attempt forcibly to land the tea. In the actual result the vessels and other property were spared from injury; the people of Boston, having carried their resolution into effect, were satisfied; the courage of the civil and military officers was unimpeached, and the “national honor” was not compromised. None but the East India Company, whose property was destroyed, had reason for complaint. A large proportion of those who were engaged in the destruction of the tea were disguised, either by a sort of Indian costume or by blacking their faces. Many, however, were fearless of consequences, and boldly employed their hands without concealing their faces from the bright light of the moon. As soon as the work of destruction was completed the active party marched in perfect order into the town, preceded by drum and fife, dispersed to their homes, and Boston, untarnished by actual mob or riot, was never more tranquil than on that bright and frosty December night.

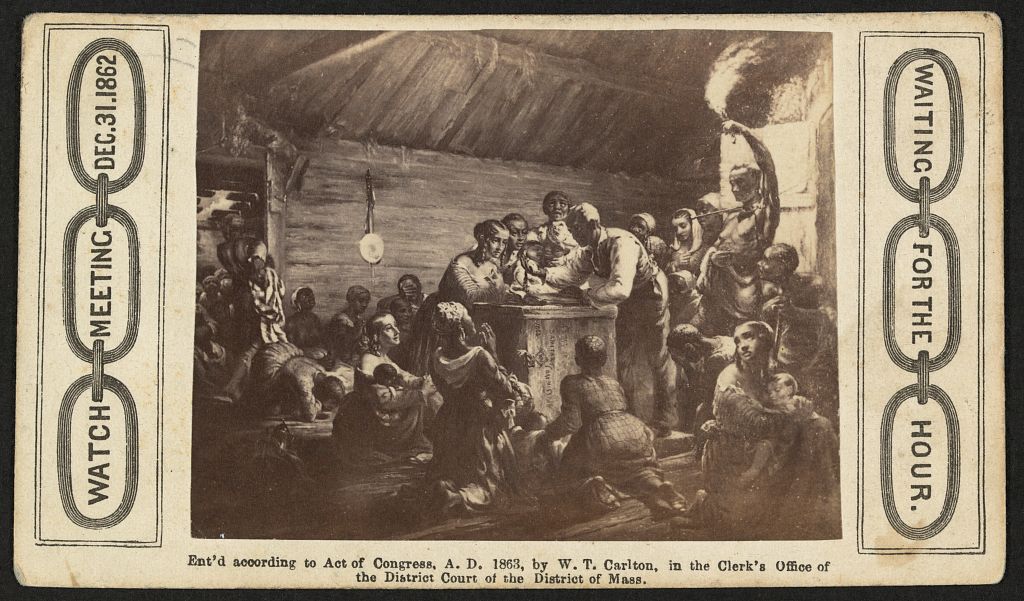

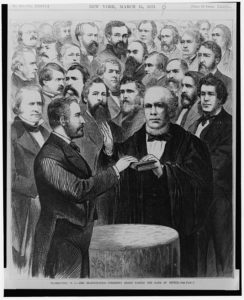

According to the National Park Service, Faneuil Hall re-enacts the 1873 Woman’s Tea Party meeting during the summer season. Read more about the 1873 meeting here. The Harper’s story above reported that Thomas Wentworth Higginson presided at the 1873 meeting. He was a Unitarian minister, radical abolitionist, and commander of “1st South Carolina Volunteers, a regiment comprised entirely of Black soldiers freed from slavery.” He wrote Army Life in a Black Regiment to “record some of the adventures of the First South Carolina Volunteers, the first slave regiment mustered into the service of the United States during the late civil war.” You can read the book at Project Gutenberg.

_____________________________________________

The 1773 tea protests were apparently only partly about taxes. After the the Seven Years’ War, the British government imposed several taxes to get the American colonists to help pay for the war. The Americans resisted. In 1767 Parliament put duties on several products, including tea. The Americans began boycotts and smuggled in tea from Holland. Parliament eventually repealed the duties, except for the one on tea. The East India Company had a monopoly on British trade with India, but by 1773 the company was in bad financial shape. The company and the British government worked out a plan to help the company. Parliament passed a law rescinding all tea duties for the East India Company except for the 1767 three pence tax. The company could sell cheap tea in America and compete with the smugglers. The colonists weren’t buying it. According to Francis S. Drake’s Tea Leaves (page xi-xiv):

The application of the East India Company to the British government for relief from pecuniary embarrassment, occasioned by the great falling off in its American tea trade, afforded the ministry just the opportunity it desired to fasten taxation upon the American colonies. The company asked permission to export tea to British America, free of duty, offering to allow government to retain sixpence per pound, as an exportation tariff, if they would take off the three per cent. duty, in America. This gave an opportunity for conciliating the colonies in an honorable way, and also to procure double the amount of revenue. But no! under the existing coercive policy, this request was of course inadmissible. At this time the company had in its warehouses upwards of seventeen millions of pounds, in addition to which the importations of the current year were expected to be larger than usual. To such a strait was it reduced, that it could neither pay its dividends nor its debts.

By an act of parliament, passed on May 10, 1773, “with little debate and no opposition,” the company, on exportation of its teas to America, was allowed a drawback of the full amount of English duties, binding itself only to pay the threepence duty[the 1767 tax], on its being landed in the English colonies.

In accordance with this act, the lords-commissioners of the treasury gave the company a license (August 20, 1773,) for the exportation of six hundred thousand pounds, which were to be sent to Boston, New York, Philadelphia and Charleston, S.C., the principal American ports. As soon as this became known, applications were made to the directors by a number of merchants in the colonial trade, soliciting a share of what promised to be a very profitable business. The establishment of a branch East India house, in a central part of America, whence the tea could be distributed to other points, was suggested. The plan finally adopted was to bestow the agency on merchants, in good repute, in the colonies, who were friendly to the administration, and who could give satisfactory security, or obtain the guaranty of London houses.

The company and its agents viewed this matter solely in a commercial light. No one supposed that the Americans would oppose the measure on the ground of abstract principle. The only doubt was as to whether the company could, merely with the threepenny duty, compete successfully with the smugglers, who brought tea from Holland. It was hoped they might, and that the difference would not compensate for the risk in smuggling. But the Americans at once saw through the scheme, and that its success would be fatal to their liberties.

The new tea act, by again raising the question of general taxation, diverted attention from local issues, and concentrated it upon one which had been already fully discussed, and on which the popular verdict had been definitely made up. Right and justice were clearly on their side. It was not that they were poor and unable to pay, but because they would not submit to wrong. The amount of the tax was paltry, and had never been in question. Their case was not—as in most revolutions—that of a people who rose against real and palpable oppression. It was an abstract principle alone for which they contended. They were prosperous and happy. It was upon a community, at the very height of its prosperity, that this insidious scheme suddenly fell, and it immediately aroused a more general opposition than had been created by the stamp act. “The measure,” says the judicious English historian, Massey, “was beneficial to the colonies; but when was a people engaged in a generous struggle for freedom, deviated by an insidious attempt to practice on their selfish interests?”

“The ministry believe,” wrote Franklin, “that threepence on a pound of tea, of which one does not perhaps drink ten pounds a year, is sufficient to overcome all the patriotism of an American.” The measure gave universal offence, not only as the enforcement of taxation, but as an odious monopoly of trade. To the warning of Americans that their adventure would end in loss, and to the scruples of the company, Lord North answered peremptorily, “It is to no purpose making objections, the king will have it so. The king means to try the question with America.” How absurd was this assertion of prerogative, and how weak the government, was seen when on the first forcible resistance to his plans, the king was compelled to apply to the petty German states for soldiers. Lord North believed that no difficulty could arise, as America, under the new regulation, would be able to buy tea from the company at a lower price than from any other European nation, and that buyers would always go to the cheapest market. …

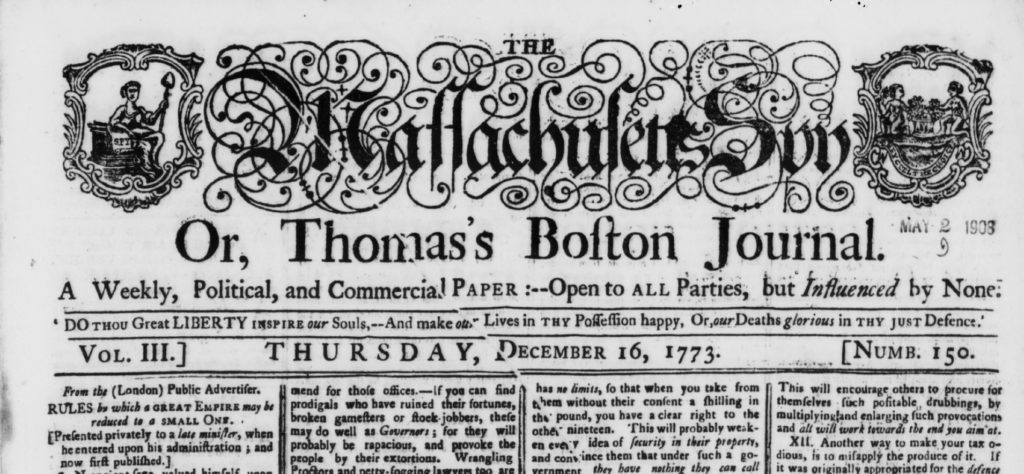

The Library of Congress has a copy of the December 16, 1773 issue of The Massachusetts Spy available. Page two includes a letter from the Marblehead Committee of Correspondence to the Boston Committee of Correspondence. At a meeting on December 7th the town passed a series of resolves that supported Boston in its attempt to prevent the tea cargo from being unloaded (on land). The second paragraph has a different way of wording the idea that “taxation without representation is tyranny”

WEDNESDAY December 15.

BOSTON.

The following is a copy of the RESOLVES of the town of MARBLEHEAD, included in a very respectful letter from the Committee of Correspondence for that town, to the Committee for the town of Boston.

At a meeting of the freeholders and other inhabitants of Marblehead, qualified to vole in town affairs according to law duly warned and legally convened, the 7th day of December, 1773, pursuant to adjournment

Deacon Stephen Phillips being Moderator.

The following resolves were unan[a]mously passed.

RESOLVED as the opinion of this town

1. That Americans have a right to be as free as any inhabitants of the earth; and to enjoy at all times, an uninterrupted possession of their property.

2. That a tax on Americans without their consent is a measure destructive of their freedom; reflecting [?] the highest dishonour on their resolutions to support it; tending to empoverish all who submit to it; and enabling to dragoon and enslave all who receive it.

3. That the late measures of of the East-India company, in sending their tea to the colonies, their tea being loaded with a duty for raising a revenue in America, are to all intents and purposes so many attempts in them and all employed by them to tax Americans; and said company as well as their factors for these daring attacks upon the liberties of America, so long and resolutely supported by the colonies, are entitled to the highest contempt, and severest marks of resentment from every American.

4. Therefore RESOLVED, That the proceedings of the brave citizens of Boston, and inhabitants of other towns in the province, for opposing the landing this tea, are rational, generous and just: That they are highly honoured and respected by this town for their noble firmness in support of American liberty; and that we are ready with our lives and interests to assist them in opposing these and all other measures tending to enslave our country.

5. That tea from Great-Britain, subject to a duty, whether shipped by the East-India Company or imported by persons here, shall not be landed in this town, while we have the means of opposing it, and that on every attempt of this kind immediate notice shall be given to our brethren in the province.

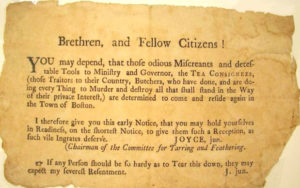

6. And whereas the tea consignees at Boston, who persist in refusing to reship the tea lately consigned them by the East-India company, have openly trifled with the forbearance of that respectable community, am thereby discovered themselves void of decency, virtue or honour.

Therefore Resolved, That it is the desire of this town to be free from the company of such unworthy miscreants; and its determination to treat them wherever to be found with the contempt which they merit; as well as to carry into execution this resolution against all such as may be any ways concerned in landing tea from Great-Britain thus rendered baneful by it duty.

Voted, That the committee of correspondence of this town be desired to obtain from the Town Clerk’s office, an attested copy of this day’s resolves, and forward the same to the Committee of Correspondence at Boston.

A true copy. Attested,

BENJAMIN BODEN, Town-Clerk

The people from Marblehead said they were ready with their lives and interests to support the cause of American liberty. Josiah Quincy’s speech at the December 16, 1773 meeting in Old South Meetinghouse warned the crowd that they’d have to pay a high price if they continued to defy the British. From Tea Leaves:

At the afternoon meeting, information was given that several towns had agreed not to use tea. A vote was taken to the effect that its use was improper and pernicious, and that it would be well for all the towns to appoint committees of inspection “to prevent this accursed tea” from coming among them. “Shall we abide by our former resolution with respect to the not suffering the tea to be landed?” was now the question. Samuel Adams, Dr. Thomas Young and Josiah Quincy, Jr., an ardent young patriot devotedly attached to the liberties of his country, were the principal speakers. Only a fragment of the speech of Quincy remains. Counselling moderation, and in a spirit of prophecy, he said:

“It is not, Mr. Moderator, the spirit that vapors within these walls that must stand us in stead. The exertions of this day will call forth the events which will make a very different spirit necessary for our salvation. Whoever supposes that shouts and hosannas will terminate the trials of the day, entertains a childish fancy. We must be grossly ignorant of the importance and value of the prize for which we contend; we must be equally ignorant of the power of those who have combined against us; we must be blind to that malice, inveteracy and insatiable revenge which actuates our enemies, public and private, abroad and in our bosom, to hope that we shall end this controversy without the sharpest, the sharpest conflicts; to flatter ourselves that popular resolves, popular harangues, popular acclamations, and popular vapor will vanquish our foes. Let us consider the issue. Let us look to the end. Let us weigh and consider before we advance to those measures which must bring on the most trying and terrific struggle this country ever saw.”

But the time for weighing and considering the business in hand had passed. Time pressed and decisive action alone remained. “Now that the hand is at the plough,” it was said, “there must be no looking back.”

After the Americans destroyed the tea, the British parliament passed the Intolerable Acts in 1774. The Revolutionary War lasted from 1775 until 1783. It was very difficult, but fortunately for the cause of the fledgling United States, not all Americans were summer soldiers and the sunshine patriots.