And the firecrackers look like fun, too

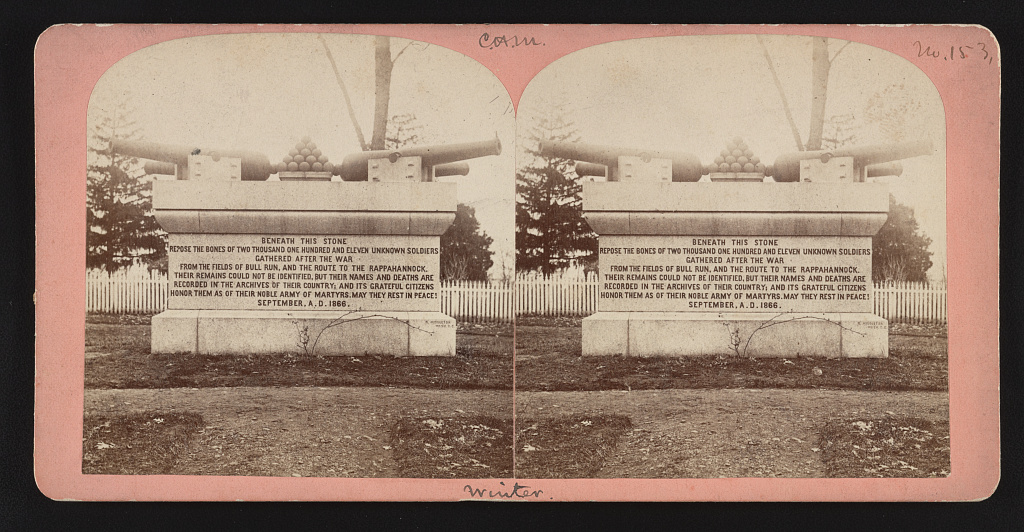

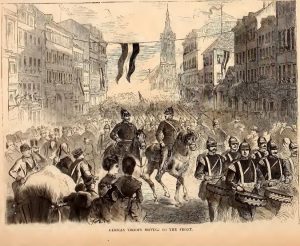

As Reconstruction was presumably trudging on, a New York City newspaper provided its readers with a couple glimpses of Christmas celebrations from the land down under, down under the Mason-Dixon line. From Harper’s Weekly December 31, 1870:

that holiday tradition

yahoo!

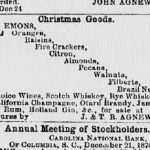

The pics piqued my curiosity, so I looked through a couple southern newspapers. I didn’t notice any specific mention of egg-nog in the December 25, 1870 issue of Columbia, South Carolina’s The Daily Phoenix, but I did notice Fire Crackers in an ad for some of the good things of the season, and the ad did include some possible egg-nog ingredients. An editorial used the Christmas story to urge its relatively well-off readers, including children, to share with the poor. Sharing children might find “the richest happiness of the day.” The paper touched on Reconstruction: “The weather has become thoroughly reconstructed, if the people have not. For the past two days it has been terribly cold. The butchers, yesterday morning, were forced to cut steaks with a saw and liver with a hatchet.”

some good Christmas goods

1870 years ago still pertinent to-day

that Yankee wind blows icy cold

____________________

Egg-nogg was mentioned in the December 24, 1870 issue of The Charleston Daily News. The author imagined a Christmas Eve party after the little ones had gone to bed. The younger adults were dancing and playing blind-man’s-bluff, while the old people sat by the fire and further warmed themselves by “sipping their egg-nogg or steaming apple-jack”

From The Charleston Daily News on December 24, 1870:

Christmas.

To-morrow is Christmas: the day of days; when the sublime harmonies which nineteen centuries ago sounded on the plains of Bethlehem are echoed in the souls of Christian millions; when the memory of the great Evangel blunts the edge of bitter sorrow; when age drives cankering care away, and youth beholds a myriad hopeful gleams in the uncertain vistas of the future!

For five years the South has struggled to heal the wounds of horrid war. The people have worked with dogged energy that they might wrest fortune from the iron teeth of adversity. It is true that the prospect is not as bright as when the summer heats ripened the silvered soil. But the people know their power. Blows and buffets have strengthened their moral fibre. They have learned the sweet uses of affliction. They, feel that, in God’s good time, self-reliance, self-reverence and self-control will give them the crowning victory.

Yet the thronging memories of four years of carnage are not obliterated by the events of five years of peace. In every breast there lingers the remembrance of martyred saints, who, in the flash of manhood or with the snows of winter on their brow, fought and bled under the gleaming banner whose stars have faded from our sight – whose cross we would gladly bear forever. These knightly soldiers – our comrades, our brothers, fathers, sons – taught the South, by their death, a lesson of endurance and fortitude, of courageous perseverance and unselfish devotion, whose fruit will live whatever else may die.

no, really

Cheerfully as we may, then, let us turn to the Christmas merry-making. It is a season of kindness and love; of charity and peace. The poor have a peculiar claim; they depend upon their prosperous neighbors for their Christmas festival. And this is the time when the sinning and the sinned against may pluck the bitterness from their hearts, and forgive as they expect to be forgiven. For them who cherish animosity and nurse their anger, however just it seem, there is no happy Christmas.

Faith in Providence, hope for the future, charity towards all men – these are the Christmas gifts which will, we trust, be found on the morrow in every home in the State.

Our Christmas Carol.

“Our song we’ll troll out for Christmas stout,

The hearty, the true and the bold;

A bumper we’ll drain, and with might and main

Give three cheers for this Christmas old.

We’ll usher him in with a merry din,

That shall gladden his joyous heart,

And we’ll keep him up while there’s bite or sup,

And in fellowship good we’ll part.”

Thank God for this returning anniversary – happy, happy Christmas; the season of all others that lights not only the fire of hospitality in the hall, but the flame of charity in the heart; the season that wins us back to the delusions of childish days, recalls to the old man the pleasures or his youth, and warms the fireside with memories of the tender, and the true. Yes, it is the only anniversary in all the year not forced upon mankind by proclamation: the only one which, in the lessons of the hour, teaches more of human sympathy and Christian love than half the homilies ever written by half the divines that have ever lived.

That man must indeed be a misanthropic sinner, who, apart from the veneration due to its sacred name and origin, can think of Christmas time as any other than a good time – a kind, forgiving, charitable, pleasant time – when men and women seem, by one consent, to open their sealed-up hearts and think of the people around them as if they really were fellow-passengers to the grave.

What sweeter I thought, too, than that there is at least one day in the year when you are sure of being welcomed wherever you go, and of having, as it were, the world thrown open to you. True, the past may be hung in mourning. Vacant chairs may be around the fireside;

the footsteps of prattling little ones may no longer lightly print tho ground; father, mother, brother, sister or husband may be celebrating their eternal Christmas before “the Jasper Throne.” Perhaps the looks of friendship that shone so brightly once have ceased to glow; the hands we grasped have grown cold; the eyes we sought have hid their lustre in the grave; yet there will come to us to-morrow “glad tidings” of even those who have gone before. The old home, the room, the merry faces, circumstances the must minute and trivial, will crowd upon our mind as if the last assemblage had been but yesterday; hope will build new fires upon the altar of the heart, and love will gather there to be renewed in the fresh and genial warmth.

Let Christmas, then, be fruitful in its joys. Let the averted faces with which we have met old friends be changed to smiles. Among the red berries and holly bushes, among the turkeys, geese and game, the pigs, sausages and oysters, the puddings, pies and punches – among emblems of the blessed season hung in every sanctuary, hall and kitchen – let us hold funeral service over all petty jealousies and private wrongs, and so bury forever the animosities that deform our human nature. At best our hearts need correcting as much as ever did the first proof of a printer’s devil, and before life’s edition is worked off another year for exportation to eternity, why ought we not to resolve that the errors which now mar the sullied page shall not stand against us when the volume of our history is finally revised by the Author of the universe? Thanking God, then, for present blessings, let us use them as the best of besoms to sweep out litter from the attics and cellars of our poor human nature, and brush down the cobwebs of care that have gathered in its dark corners. Nor should we extend these favors to the body, and, as it were, put a clean shirt upon the soul, for the reason that “to-morrow we die;” but we are to do these in remembrance of the time when a sin-sick world first began to experience the cheering symptoms of convalescence.

To-morrow the civilized world – all peoples and nations, knit together by a mighty thought – will become one great family. Happy bells will send as their greetings to each Christmas fire –

“Good will and peace! peace and good will!

The burden of the Advent Song.”

And in a myriad of homes, the same festival that every year has stirred the heart of mankind, will again gather youth and age around the happy fireside.

A Christmas family party! What magic there is in the name. What man or woman, sending memory on its grateful errand, does not linger with a Hush of happiness upon the associations that are recalled. The coming home from school, tho greeting of parents, brothers, sisters, cousins and aunts; the welcome of the old-time nurse in her fresh bandana and immaculate neckerchief; the roaring fires in the parlors and bed-rooms; the wonderful hampers, and the handsome girls hooded and booted for any sort of Christmas fun. And Christmas Eve! How the great tree – very mighty in our young imagination – planted in the middle of the table, sparkles with its multitude of little tapers that find reflection in our dancing eyes, while we wait for the distribution of the toys, that peep like fairies from among the leaves. Grandpapa and grandmama are there; brothers who have just come from school and college; uncles from the cities, and maiden aunts, with pockets full of love and bon-bons. By-and-by, bed-time arrives, and we little ones are sent to dream of Santa Claus, and wonder what our stockings will be freighted with, when at daylight we hurry from our trundles to the chimney jam. The evening concludes with the time-honored Christmas dance, and a glorious game of blind-man’s-bluff, in which the pretty girls take refuge behind the window curtains, and get mad if you fail to make your eliptical salutes with a vim. The old people, all delight, sit in the cosiest corner of the fire-place, and sipping their egg-nogg or steaming apple-jack, watch with glistening eyes the lively youngsters who remind them of Merry Christmas long ago. King among the musicians is the hoary-headed old Ethiopean, who has played dance-music in the family for a quarter of a century, and tonight, all mellowness, he scrapes his fiddle until it shrieks with fifty stomach aches; while dusky house-servants, peeping in at the windows and door-ways, keep time with nimble feet to the jollity of the hour, and all goes “merry as a music bell.” And so ends Christmas Eve, but only to usher in the cheerfulness of the day to come. And that day! Ah, how crowded with memories. Memories of a home-gathering of all the accessible members of the family circle; of home ties renewed, and love warming every heart. Memories of your mother, who, with tender thoughtfulness, and grateful for her own pleasure, has sent heaping baskets of good things to the families of her poor neighbors, who, but for her largesse, would have had no Christmas. Memories of the last Christmas blessing ever asked by him who presided; of a room all aglow with ruddy light, and a board spread with such an array of feathered phenomenon in every stage of sissing excellence, gigantic puddings blazing in brandy, and choice wines, with the bouquet of whole generations in them, as make us think, in these changed times, we have been living in a dream.

But no! Christmas is just as real to us to-day as it ever was to our forefathers. Our children will recall its happy scenes, just as we gather the tangled ends of our own reminiscences. Friends are as true, and affections as tender around us, now, as when we ourselves were budding into serious men and women; and if we do our duty, changed as may be our circumstances, the season will preserve all its sacred charm for us and our little ones; and the lesson will continue to be written upon our hearts- “This do in remembrance of Me!” And so, a Merry Christmas to you all, and GOD BLESS US, EVERY ONE!

Remember the Poor.

The season of gladness is upon us. In happy homes to-day begins the rosy reign of mirth and jollity and innocent rejoicing. The Christmas tree is already blossoming in some hidden recess with its wondrous, but, as yet, forbidden fruit. The blithe and expectant little ones are making ready to hang their stockings by the chimney-piece, with grave misgivings as to their capacity to hold the good things to be distributed in the night-time by the slyly-generous Santa Claus. Families are everywhere gleeful with the anticipation of merry gatherings around the plenteous board and festive libations from the foaming bowl. Bleak and wintry though the sky be out of doors, around the hearthstone joy and comfort and social happiness rule the hour.

But not to all homes will Christmas bring the appropriate merry makings and delights. Right here, in this good old City of Charleston, there is many a family whose desolate hearth glows not, even in this bitter weather, with the ruddy blaze of the yule log, or of any substitute, and to whom one plain hearty meal would be a Christmas feast indeed. To these unfortunates, too many of whom have known better days, let each man, woman and child, who reads these lines at the breakfast table this Christmas Eve, give something better than mere sympathy. There are several noble relief societies in our community, ready and anxious to relieve the charitable of the trouble and responsibility of seeking out the distressed and really deserving poor. The Fuel Society, especially, crave assistance to-day; and the biting December blasts dismally second their pleading. Any Christmas offerings, either in money or fuel, that may be sent to the office of THE NEWS will be promptly placed at the disposal of the good ladies of the society.

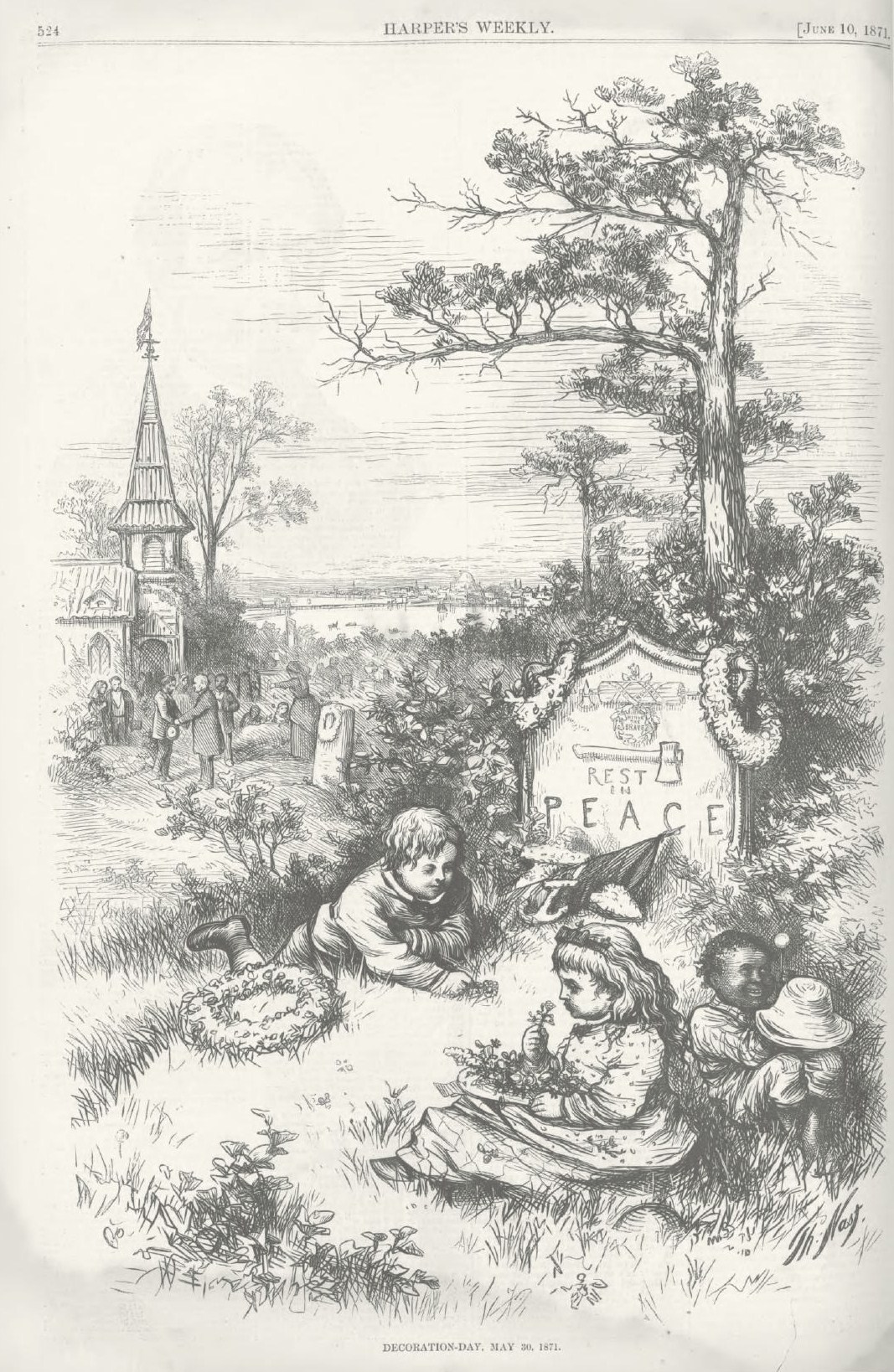

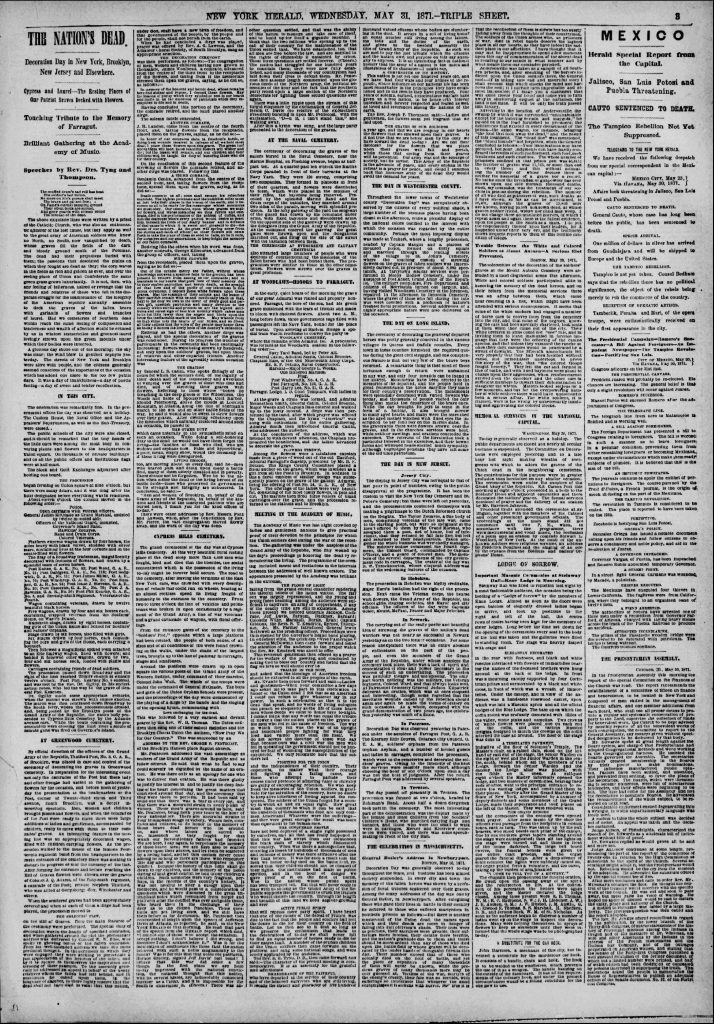

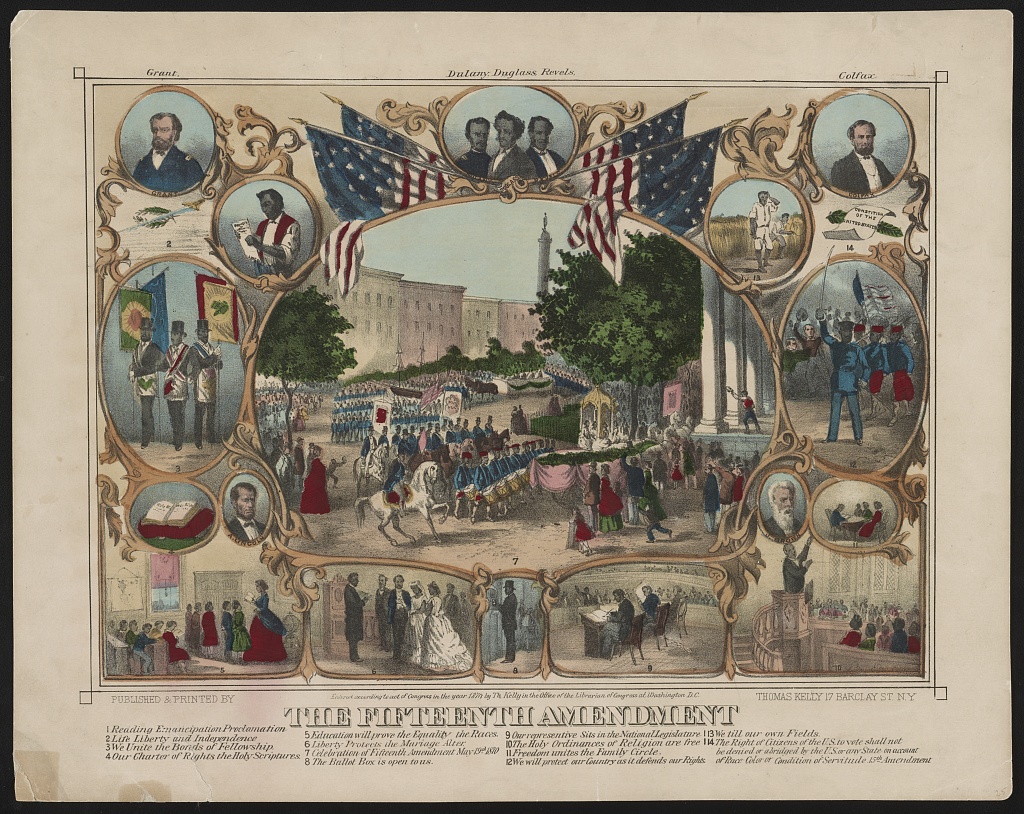

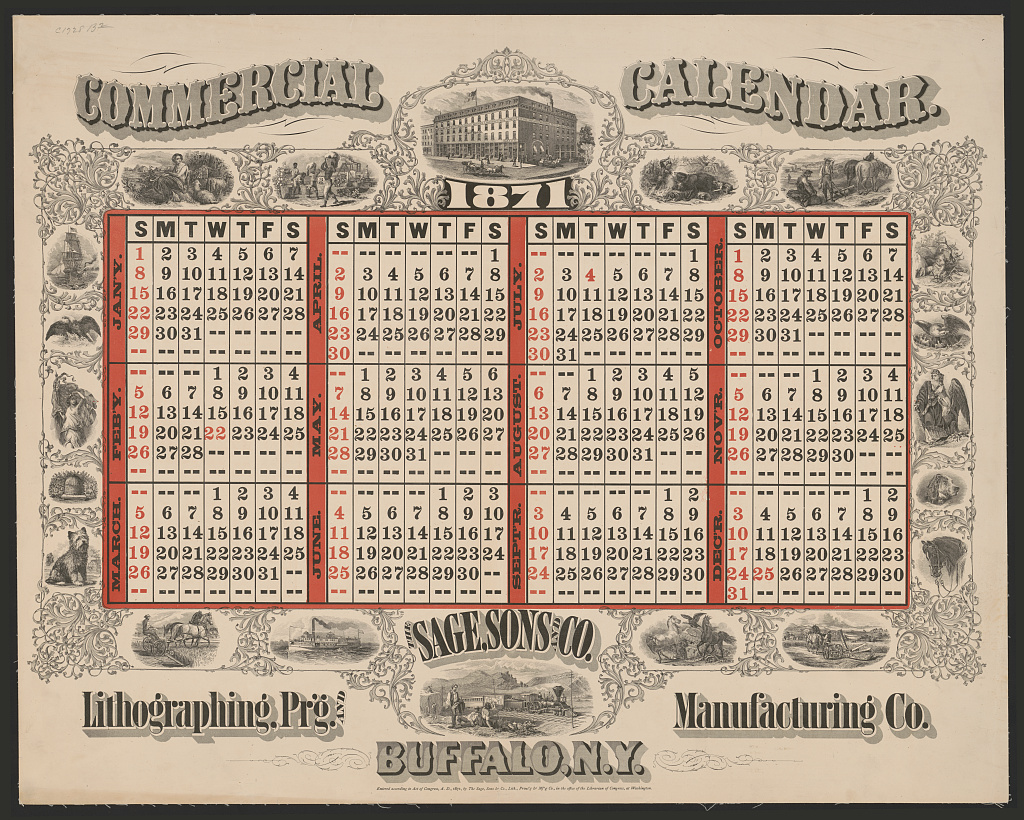

You can find Harper’s Weekly for all of 1870 at the Internet Archive – the two pictures below are also from December 31st. From the Library of Congress: sheet music; Currier & Ives’ graphic greeting. According to Wikipedia southerner George Washington “served an eggnog-like drink to visitors” – the drink included four different types of alcohol. Tiny Tim said, “God bless us, every one!” in A Christmas Carol – author Charles Dickens died on June 9, 1870.

Christmas is for children

holidays cheer

![Merry Christmas (New York : Published by Currier & Ives, 125 Nassau St., [1876])](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/09454v-1024x812.jpg)

traditional greeting

![Merry Christmas (New York : Published by Currier & Ives, 125 Nassau St., [1876])](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/09454v-1024x812.jpg)