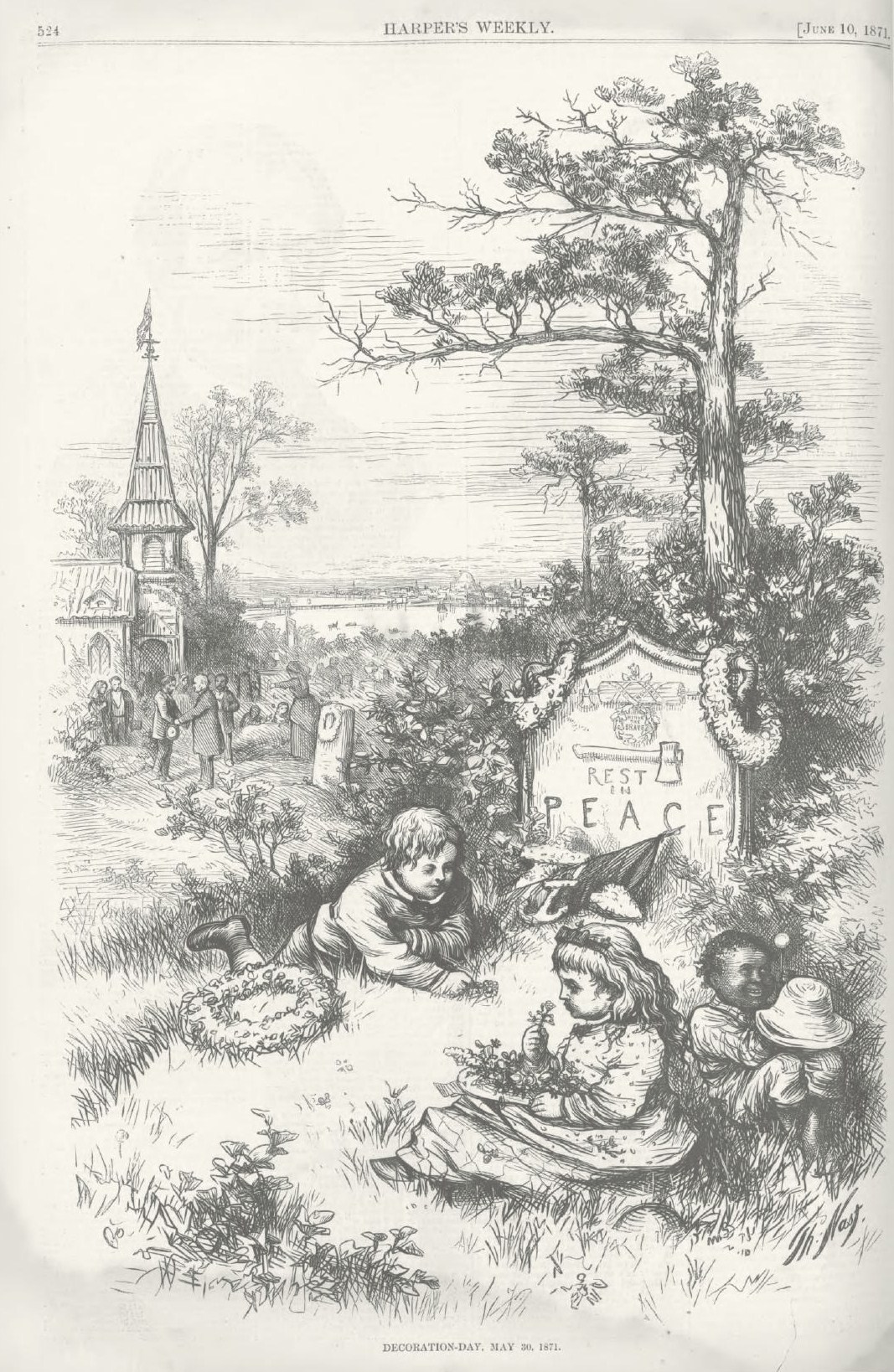

From the June 10, 1871 issue of Harper’s Weekly:

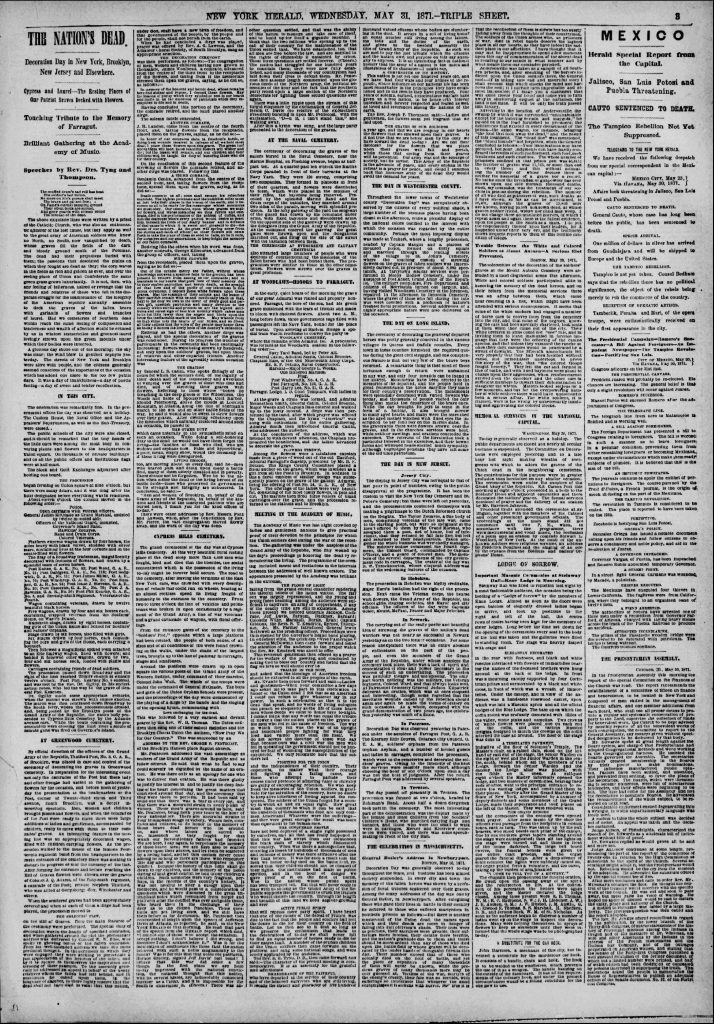

From the The New York Herald May 31, 1871:

THE NATION’S DEAD. …

The muffled drum’s sad roll has beat

The Soldier’s last tattoo,

No more on life’e parade shall meet

The brave and gallant few;

On Fame’s eternal camping ground

Their silent tents are spread,

And glory guards with solemn round

The bivouac of the dead.

The above exquisite lines were written by a priest of the Catholic Church, who was also an enthusiastic admirer of the lost cause, but they apply as well to the great army of American soldiers who knew no North, no South, now vanquished by death, whose graves fill the fields of the dark and bloody ground south of the Potomac. The dead had their prejudices buried with them; the passions that desolated the plains on which they fought are dead as they; the corn waves in the fields as rich and golden as ever, and over the resting place of Union and Confederate the same green grass grows luxuriantly. It is not, then, with any feeling of bitterness, hatred or revenge that the friends and relatives of those who fell in the desperate struggle for the maintenance of the integrity of the American republic annually assemble to deck the graves of the fallen brave with garlands of flowers and branches of laurel. Had we cemeteries of Southern dead within reach the same feeling of compassion and tenderness and wealth of affection would be evinced by us in whitest immortelles and greenest laurel lovingly strewn upon the green mounds under which their bodies were interred.

A glorious day shone out of the morning; the sky was clear; the wind blew in gentlest zephyrs yesterday. The streets of New York and Brooklyn were alive with people, and the citizens generally seemed conscious or the importance of the occasion which has added one more to the too few public days. It was a day of thankfulness – a day of poetic feeling – a day of sweet and tender recollection. …

At Woodlawn cemetery Admiral Farragut’s grave was honored. It close to violence in Boston when White and black soldiers returning from Mount Auburn had a disagreement about who could ride on the horse cars engaged by white troops. It was alleged that white troops made matters worse by insulting the blacks.

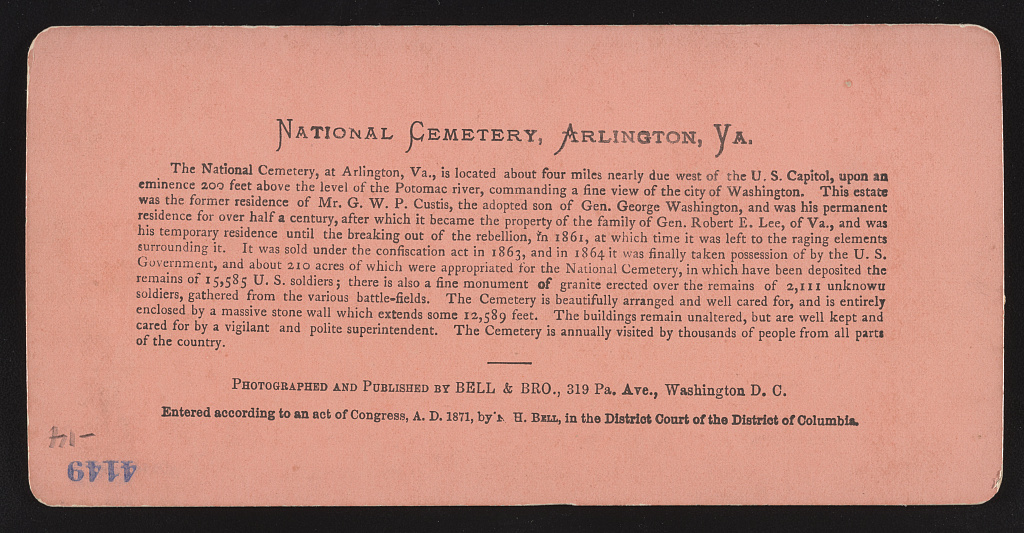

And, with President Grant and Cabinet members in attendance, Frederick Douglass spoke at the Tomb of the Unknown at Arlington National Cemetery. This is his speech according to What So Proudly We Hail:

Friends and Fellow Citizens:

Tarry here for a moment. My words shall be few and simple. The solemn rites of this hour and place call for no lengthened speech. There is, in the very air of this resting-ground of the unknown dead a silent, subtle, and an all-pervading eloquence, far more touching, impressive, and thrilling than living lips have ever uttered. Into the measureless depths of every loyal soul it is now whispering lessons of all that is precious, priceless, holiest, and most enduring in human existence.

Dark and sad will be the hour to this nation when it forgets to pay grateful homage to its greatest benefactors. The offering we bring to-day is due alike to the patriot soldiers dead and their noble comrades who still live; for, whether living or dead, whether in time or eternity, the loyal soldiers who imperiled all for country and freedom are one and inseparable.

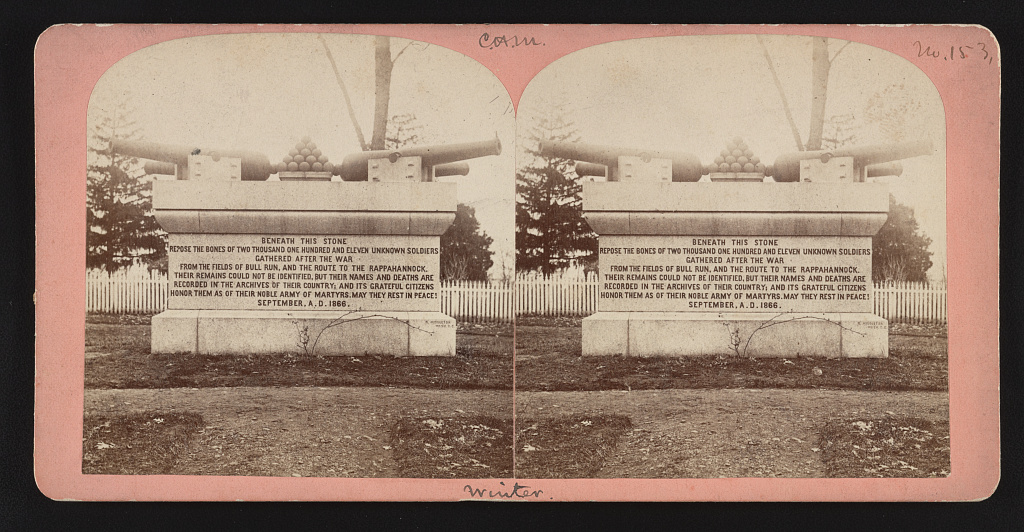

Those unknown heroes whose whitened bones have been piously gathered here, and whose green graves we now strew with sweet and beautiful flowers, choice emblems alike of pure hearts and brave spirits, reached, in their glorious career that last highest point of nobleness beyond which human power cannot go. They died for their country.

No loftier tribute can be paid to the most illustrious of all the benefactors of mankind than we pay to these unrecognized soldiers when we write above their graves this shining epitaph.

When the dark and vengeful spirit of slavery, always ambitious, preferring to rule in hell than to serve in heaven, fired the Southern heart and stirred all the malign elements of discord, when our great Republic, the hope of freedom and self-government throughout the world, had reached the point of supreme peril, when the Union of these states was torn and rent asunder at the center, and the armies of a gigantic rebellion came forth with broad blades and bloody hands to destroy the very foundations of American society, the unknown braves who flung themselves into the yawning chasm, where cannon roared and bullets whistled, fought and fell. They died for their country.

We are sometimes asked, in the name of patriotism, to forget the merits of this fearful struggle, and to remember with equal admiration those who struck at the nation’s life and those who struck to save it, those who fought for slavery and those who fought for liberty and justice.

I am no minister of malice. I would not strike the fallen. I would not repel the repentant; but may my “right hand forget her cunning and my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth,” if I forget the difference between the parties to that terrible, protracted, and bloody conflict.

If we ought to forget a war which has filled our land with widows and orphans; which has made stumps of men of the very flower of our youth; which has sent them on the journey of life armless, legless, maimed, and mutilated; which has piled up a debt heavier than a mountain of gold, swept uncounted thousands of men into bloody graves and planted agony at a million hearthstones—I say, if this war is to be forgotten, I ask, in the name of all things sacred, what shall men remember?

The essence and significance of our devotions here to-day are not to be found in the fact that the men whose remains fill these graves were brave in battle. If we met simply to show our sense of bravery, we should find enough to kindle admiration on both sides. In the raging storm of fire and blood, in the fierce torrent of shot and shell, of sword and bayonet, whether on foot or on horse, unflinching courage marked the rebel not less than the loyal soldier.

But we are not here to applaud manly courage, save as it has been displayed in a noble cause. We must never forget that victory to the rebellion meant death to the republic. We must never forget that the loyal soldiers who rest beneath this sod flung themselves between the nation and the nation’s destroyers. If to-day we have a country not boiling in an agony of blood, like France, if now we have a united country, no longer cursed by the hell-black system of human bondage, if the American name is no longer a by-word and a hissing to a mocking earth, if the star-spangled banner floats only over free American citizens in every quarter of the land, and our country has before it a long and glorious career of justice, liberty, and civilization, we are indebted to the unselfish devotion of the noble army who rest in these honored graves all around us.