150 years ago this week Gothamites could read about the Union prison at Fort Delaware. One of correspondent “C.B.”‘s first impressions was of the stench of “ten thousand idle and dirty men.” The southern prisoners are seen as mostly listless, dirty, and ignorant. C.B. seeeds surprised that some of the rebels actually felt it was their duty to honor their oaths to the CSA. Northern culture was superior, but the war was just a brief interlude before North and South reunited to implement the Monroe Doctrine. Here are some excerpts.

From The New-York Times August 31, 1863:

FORT DELAWARE.; An Inside View of Captive Rebeldom.

WILMINGTON, Del., Saturday, Aug. 22, 1863.

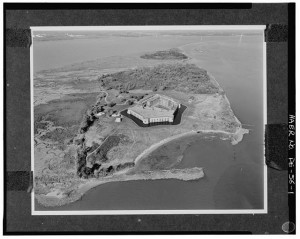

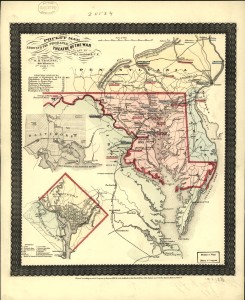

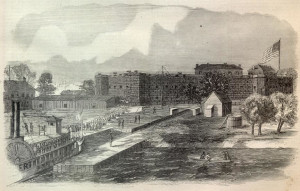

About sixteen miles below this city, on the Delaware River, there is a small island, of an irregular lozenge or diamond shape, its longer axis pointing North and South, covering about one hundred and fifty acres, and naturally liable to be submerged at high tide. This island, which was formerly known as the Pea-patch, and occasioned many years ago that famous lawsuit for its ownership, between the neighboring States of New Jersey and Delaware, in which JOHN M. CLAYTON so distinguished himself in his successful advocacy of the claims of Delaware, is now known as Fort Delaware, and belongs to the United States. … Upon this island is now to be found the largest collection of rebel prisoners in the United States.

Yesterday we visited the Fort by means of the Government steamer, attached to the Island. Our trip down the bay was enlivened by a fine band of music detailed from the United State service, and was so short that we all wished it longer. From the north, the island presents the rebel barracks first to the eye of the visitor.

From an outside view these barracks present the appearance of eight or ten long, high-roofed yellow buildings, evidently new, about twice the height of the Park barracks in New-York, to which they are much superior, and occupying a space a few acres in extent. A southerly wind was blowing, and when we came within half or a quarter of a mile of this portion of the Island, we became aware of a peculiar and penetrating odor; an odor in regard to whose merits and characteristics Trinculo, in the “Tempest,” would have been good authority; and which I can best compare to a compound, resulting from a mixture of atmospheres from a soap-house, a tenement-house chamber, and a ward-school room in a wet day. This dense mass of disagreeable and penetrating gases, which were not the gases of the sewer, nor of any accustomed form of fifth, came over the water in a well-defined current, and indicated the proximity of ten thousand idle and dirty men. And this is as distinct a personal reminiscence of yesterday, as that I breathed before and afterward the vital air.

We gained our first view of the rebel prisoners as we landed. There is always more or less work to be done at the docks, in digging, unloading supplies and stores, and carrying timber, and for this purpose rebel prisoners are employed along with United States military convicts. There was no mistaking the peculiar uniform of the rebels; the dingy gray linsey or cotton trowsers, and the Unbleached cotton shirt in which these warriors fight, and live, and die. But these were mere stragglers. The grand army is to be found in the barracks.

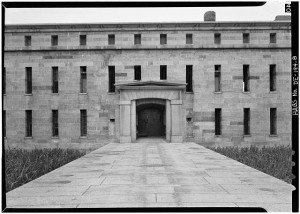

The plan of the barrack is simple. Each one, in the shape of a parallelogram, incloses a space of about 300 feet in length, by 125 in breadth. The side barracks are occupied by prisoners. The end barracks are occupied by our men as offices and sleeping apartments. The entrance to each of these inclosures is very narrow, and is guarded at each extremity by two soldiers, so that four soldiers with loaded pieces might instantly occupy the passage at either extremity in case of alarm; and as they are supported by similar squads on patrol near at hand, and as the patrol have the means of summoning the entire armed force of the island, whose number it might be inexpedient to state, but which is enough and more than enough to put down any possible outbreak, the prisoners are as docile and quiet as men of naturally good tempers are when they know that it is of no use to be fractious. The general friendliness and good nature of the Southern man, and especially the Southern poor white, when not inflamed by influences acting from without, is now quite well understood at the North; and the listless, lazy multitudes who lounge upon the parched and trodden surface of these prison-bar-rack quadrangles, appear to harbor thoughts neither of revenge nor escape.

The reader may imagine a space equal to perhaps four city lots, surrounded by low wooden buildings with plenty of airholes but no windows, trodden upon and tenanted by a thousand men and boys, clothed in dirt-colored kersey pantaloons and unbleached shirts. I omit the mention of other articles of dress, for in attempting a true picture. I am not allowed to draw upon the imagination Whether one-half the prisoners have hats may be a question, but there is no question that the larger portion are destitute of shoes or boots; and as for coats, the prisoner who has one is a fortunate and marked man. These prisoners are clothed in the manner in which they were clothed when we took them, and it may be that their lack of coats is owing to their habits of removing their coats preparatory to making a charge, for it is hardly conceivable that men should conduct campaigns in shirt-sleeves only. However, here they are, lounging up and down this bare, blank, treeless, multitudinously trodden dirt floor, mostly hatless, shoeless, with unbuttoned shirts, with trowsers in a state of inconceivable widowhood from buttons, with frowsy, uncombed hair, and with faces sunburned, bronzed, and grimed with the fifth of the barracks. They play no games except cards inside the barracks; no foot-ball, baseball, leap-frog — nothing. They neither sing nor dance. Ignorance and the isolated, artless, vacuous life which they have led at home, renders them strangers to the numerous and changeful resources by which the Yankee prisoners relieve the tedium of confinement. One sees here a different race from the busy, social, adaptative Northerner; or, more correctly, a different aspect of the same race, indicating the effect of an isolated, simple life, deprived of education and of the lively companionship of the mechanic arts. They are men of direct and simple-minded aims, having few objects in life to look forward to; their horizon on all sides contracted. At home they saunter, and having by the minimum of labor procured enough to eat, (and they are easily satisfied,) they know of only two amusements, cards and shooting. Removed to the prison barracks, they can only saunter. And this they do, all day and every day, and would do so for ten years, and at the end of that time would be just what they are to-day; if not satisfied, yet not mutinous; and if not happy, yet not miserable. Regrets for home, and kindred, and wives, and sweethearts, they have, of course, and into such emotions of nature it does not become the mere spectator of the prisoner to pry or question; yet these are deprivations which soldiers make up their minds to risk, and in this regard the man of the South may not differ from the man of the North.

In passing through one of the barracks, my eye was arrested by a remarkably good-looking young fellow, and it occurred to me to inquire of him if it would not be wise on his part to leave the rebel service and take the oath of allegiance, to the United States. “What would you think of a man,” he replied, “who would take two oaths?” This is a common sentiment among the prisoners. Their direct and simple natures, capable of appreciating an oath, and incapable of discrimination between the obligation of a righteous and voluntary oath, and the letter of an unrighteous and forced oath, having once consented to the Confederate tribute, for the most part continue to do so, and like the natures of narrow-minded men the world over, defy argument; and thus it is, that the myriad of captives at Fort Delaware, haunted by vermin, and confined to barren inclosures of trodden clay, regard the above question as the test of patriotic endurance, and decline to be free if they must first be forsworn.

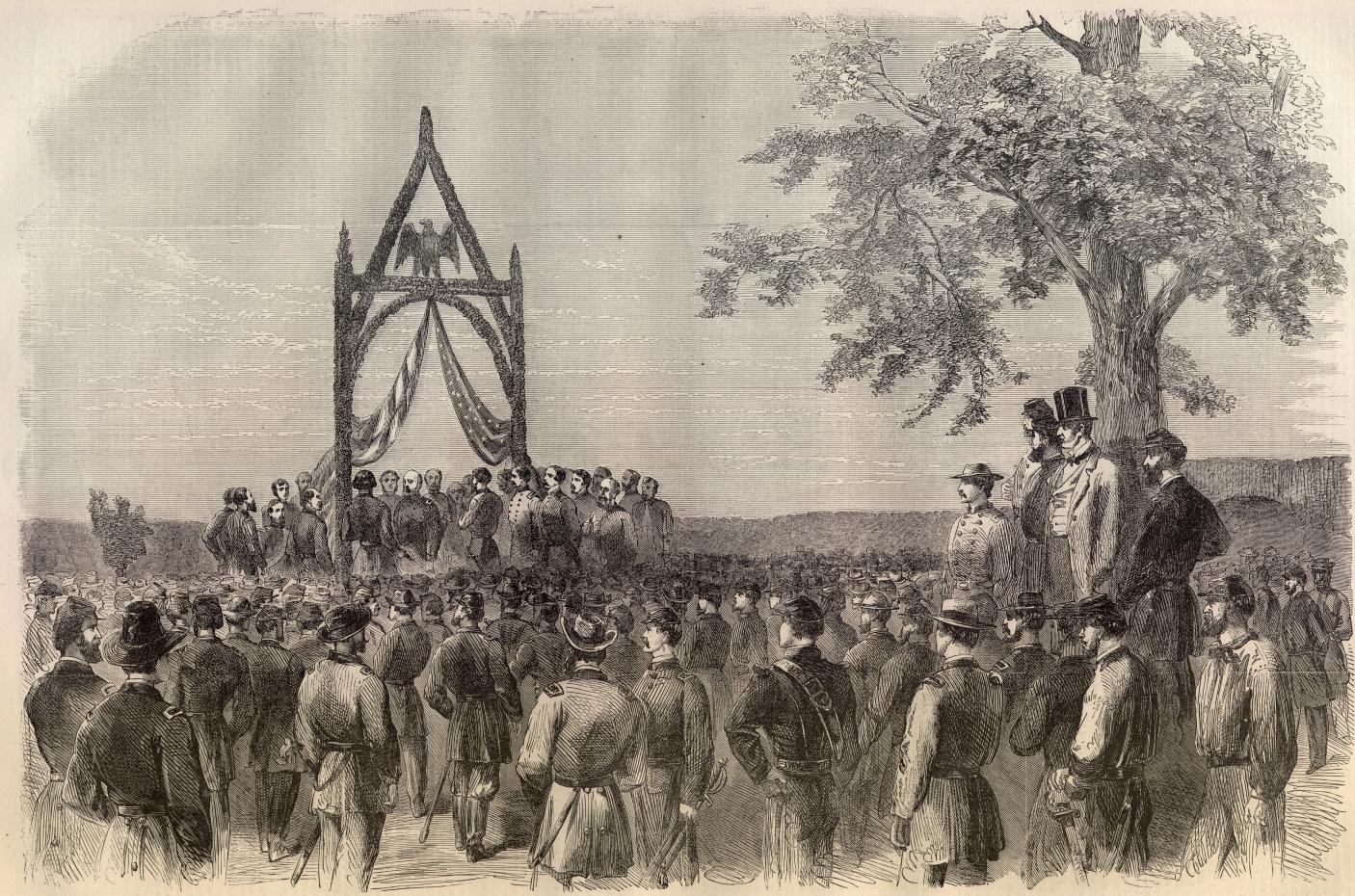

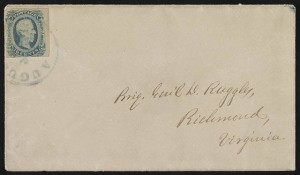

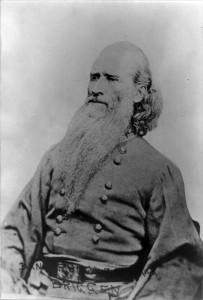

About seven hundred, however, of the ten thousand — and it seemed to me a better-looking body of men than the average of the prisoners — have taken the oath, and Gen. SCH[O]EPF, the Commander of the post, is now organizing them into cavalry regiment for the Union service. The General, who has had a European experience, and understands the nature of the bayonet or saber that is borne on both sides of a war, does not admit into this regiment any prisoner who has property at the South, or a wife and family there. Having thus excluded from this organization the elements of revolt, he finds in the simple-natured, docile, easily-satisfied Southern soldier, excellent material for a regiment. Four companies of these men are already attired in the Union uniform; and the General pointed them out with pride and satisfaction as they marched across the island to dress parade. The time has come when it is not invidious to do justice to the good military qualities of the Southern soldier, and Gen. SCHAEPF is not slow to predict a successful career to this novel regiment, which the rebel ten thousand style ” galvanized rebs.”

We found among the prisoners a little boy, only 12 years of age, and small for his years, who was pressed into a cavalry regiment at Augusta, Ga. This case is somewhat peculiar, yet, on traversing the barracks, one could not fail to notice how freely the very young and the more than middle-aged men entered into the composition of the rebel army. Grizzly hair was very common, and gray hair not uncommon. The Southern conscriptors, sweeping through the outlying hamlets of the South, had evidently taken father and sons together.

One branch of industry flourishes in the barracks; the manufacture of finger-rings from black gutta-percha buttons. These the rebels make in great numbers, and inlaying them with hearts, crosses, and lozenges, of silver, sell them to visitors at from twenty-five to fifty cents each. These men do not despise the commercial spirit, for no sooner had our party stopped to examine the collection of one of these artists, than several competitors surrounded us, displaying similar wares, and several dozen sympathizers with the individuals who were about to perform the marvellous feat of selling Southern manufactures to Yankees, having gathered closely around us, we were forced to break off negotiations after a few purchases, with a view to obtain fresh air. I may here venture to say that it is dangerous in certain points of view, to indulge one’s self in the society of the rebel soldiery. The majority of them are not entirely unconnected with entomological collections; and yet some of them really wash themselves. They are allowed to bathe in the Delaware river, of course under the muskets of the sentries. During the two or three warm Summer afternoon hours in which I was with them, three men out of the ten thousand, it seemed, availed themselves of this privilege! I suppose that, living on the sandy and arid plains of the interior South, they never learn to wash themselves. Nor are their ideas of water at all correct. Government supplies their barracks with thirty thousand gallons of pure water daily from the Brandy wine River. This is conveyed to large tanks, accessible to all the prisoners at a minute’s walk; yet numbers of them refuse, from sheer laziness, to avail of the tanks, and, when thirsty, stoop and drink of the brackish waters of the canals that numerously intersect the open spaces of the barracks, and in which the others wash. Such things read oddly, and they look oddly too. A Northerner, accustomed to the oaken bucket of the ancestral well, might with difficulty credit my statements.

Twelve hundred letters reach the island daily for the prisoners, which are duly read and distributed, if not contraband. More or less money is constantly sent them, which they are allowed to spend at the sutler’s, a Union soldier acting as the go-between. The rebels buy in this way, molasses, fruit, extra pork, pie and milk. They are not allowed to buy spirits. The inner portion of’ the sea wall on the west side of their quarters, is constantly alive with cooks, operating over chip fires, with fire pans in which they fry pork, crackers, crumbs, little fish taken from the ditches and pie. A fried pie seems, from some reason or other, to be the most desirable, as it is, perhaps, the most expensive of these superadded and greasy luxuries. Imagine on the sloping foot of an embankment fifty or sixty individuals, such as I have described, begrimed with smoke and dirt, melting with the heat of the sun above and the fire below, a curious and motley crowd behind them, staring with envious eyes at the fortunate kitcheners, rich in fruition of crackers, skinned eels, pork-chop, and admantine pie. This is the culinary apex of rebel prisonerdom. …

Only four deaths take place a day. This from among 10,000 idle men speaks well for the sanitary management of the post. The principal disease at the post is typhoid fever. The hospitals are well aired, and the sick are kindly cared for aud supplied with good reading matter. All the prisoners have access to books and tracts of a religious nature, which they do not greatly addict themselves to while in health; but when ill, such of them read as are able to read. A large proportion, however, are too ignorant. …

But I must close this already too long letter, leaving much unsaid that might interest those who are disposed to be interested in the Southern character — and who of us are not? For who doubts that the Northern and Southern armies will some day, not distant, march in accord, to the support of the MONROE DOCTRINE? C.B.

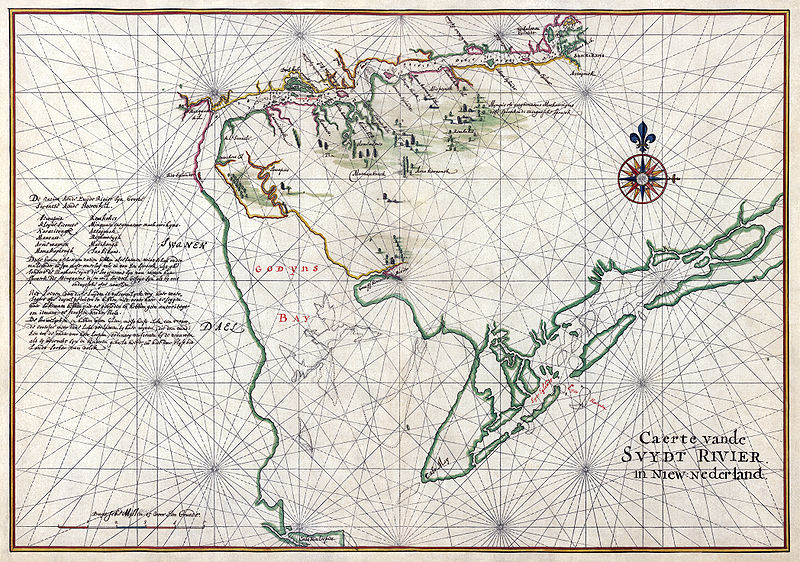

It is written that the Marquis de Lafayette first proposed using Pea Patch Island for a fort. This link will also take you to a description of the following 1639 map:

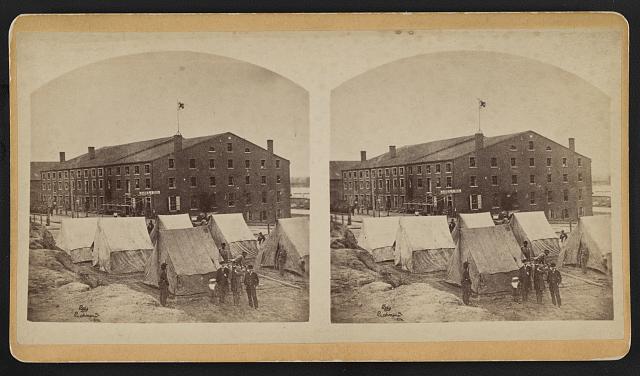

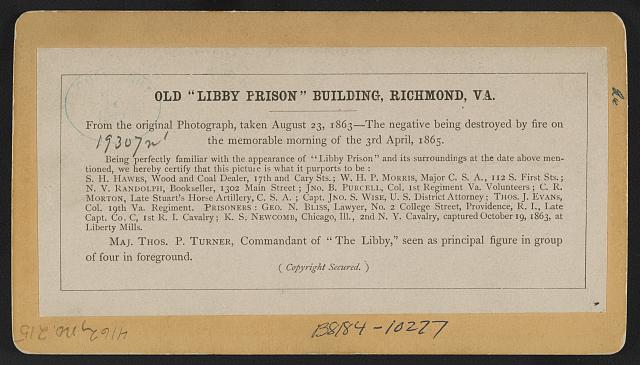

![Plan of part of Richmond, Virginia : showing locations of Rebel prisons [in] winter of 1863. (by Robert Knox Sneden; LOC: vhs01 vhs00025 http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.ndlpcoop/gvhs01.vhs00025)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/jp2.py_.jpg)