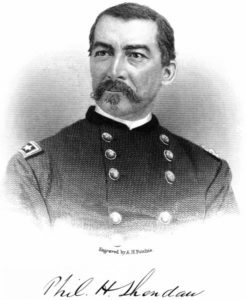

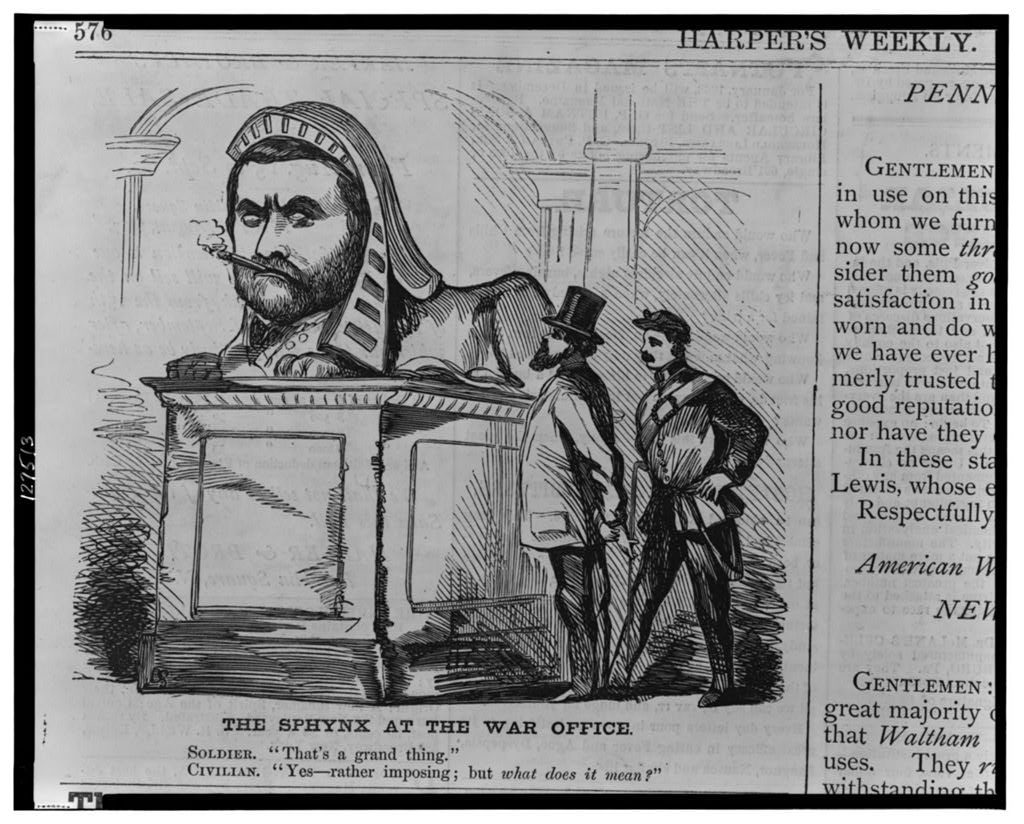

too radical for the president

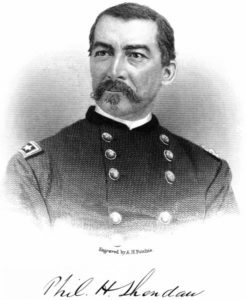

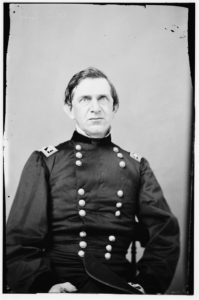

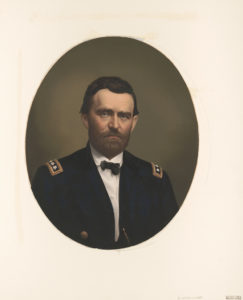

On August 12th President Andrew Johnson suspended Edwin M. Stanton and named General U.S. Grant as acting Secretary of War. 150 years ago today the president ordered the general to make some changes. Philip Sheridan was to be removed from command of the Fifth Military District (Louisiana and Texas) and replaced by George Thomas. There was some give and take; General Grant tried to stick up for Sheridan; General Thomas was reportedly ill. Eventually General Winfield Hancock assumed command of the Fifth District and Sheridan replaced him in the Department of Missouri. Here’s how General Sheridan remembered the events in his 1888 book. Registration referred to registering voters to elect delegates to a state constitutional convention. President Johnson was “outraged” that Sheridan sent a letter to Grant on June 22nd trying to “evade the president’s order to extend the registration period in Louisiana” and disagreeing with Attorney-General Stanbery’s interpretation of the Reconstruction Acts. Mr. Stanbery said that existing state governments and civilian courts should have more authority than the military governments.[] General Sheridan seems to have gotten the timing wrong about when the president decided to remove him.

From the Personal Memoirs of General P. H. Sheridan (1888; at Project Gutenberg; Volume II, Chapter 11):

In accomplishing the registration there had been little opposition from the mass of the people, but the press of New Orleans, and the office-holders and office-seekers in the State generally, antagonized the work bitterly and violently, particularly after the promulgation of the opinion of the Attorney-General. These agitators condemned everybody and everything connected with the Congressional plan of reconstruction; and the pernicious influence thus exerted was manifested in various ways, but most notably in the selection of persons to compose the jury lists in the country parishes it also tempted certain municipal officers in New Orleans to perform illegal acts that would seriously have affected the credit of the city had matters not been promptly corrected by the summary removal from office of the comptroller and the treasurer, who had already issued a quarter of a million dollars in illegal certificates. On learning of this unwarranted and unlawful proceeding, Mayor Heath demanded an investigation by the Common Council, but this body, taking its cue from the evident intention of the President to render abortive the Reconstruction acts, refused the mayor’s demand. Then he tried to have the treasurer and comptroller restrained by injunction, but the city attorney, under the same inspiration as the council, declined to sue out a writ, and the attorney being supported in this course by nearly all the other officials, the mayor was left helpless in his endeavors to preserve the city’s credit. Under such circumstances he took the only step left him—recourse to the military commander; and after looking into the matter carefully I decided, in the early part of August, to give the mayor officials who would not refuse to make an investigation of the illegal issue of certificates, and to this end I removed the treasurer, surveyor, comptroller, city attorney, and twenty-two of the aldermen; these officials, and all of their assistants, having reduced the financial credit of New Orleans to a disordered condition, and also having made efforts—and being then engaged in such—to hamper the execution of the Reconstruction laws.

This action settled matters in the city, but subsequently I had to remove some officials in the parishes—among them a justice of the peace and a sheriff in the parish of Rapides; the justice for refusing to permit negro witnesses to testify in a certain murder case, and for allowing the murderer, who had foully killed a colored man, to walk out of his court on bail in the insignificant sum of five hundred dollars; and the sheriff, for conniving at the escape from jail of another alleged murderer. Finding, however, even after these removals, that in the country districts murderers and other criminals went unpunished, provided the offenses were against negroes merely (since the jurors were selected exclusively from the whites, and often embraced those excluded from the exercise of the election franchise) I, having full authority under the Reconstruction laws, directed such a revision of the jury lists as would reject from them every man not eligible for registration as a voter. This order was issued August 24, and on its promulgation the President relieved me from duty and assigned General Hancock as my successor.

“HEADQUARTERS FIFTH MILITARY DISTRICT,

“NEW ORLEANS, LA., August 24, 1867.

“SPECIAL ORDERS, No. 125.

“The registration of voters of the State of Louisiana, according to the law of Congress, being complete, it is hereby ordered that no person who is not registered in accordance with said law shall be considered as, a duly qualified voter of the State of Louisiana. All persons duly registered as above, and no others, are consequently eligible, under the laws of the State of Louisiana, to serve as jurors in any of the courts of the State.

“The necessary revision of the jury lists will immediately be made by the proper officers.

“All the laws of the State respecting exemptions, etc., from jury duty will remain in force.

“By command of Major-General P. H. SHERIDAN.

“GEO. L. HARTNUFF, Asst. Adj’t-General.”

Pending the arrival of General Hancock, I turned over the command of the district September 1 to General Charles Griffin; but he dying of yellow fever, General J. A. Mower succeeded him, and retained command till November 29, on which date General Hancock assumed control. Immediately after Hancock took charge, he revoked my order of August 24 providing for a revision of the jury lists; and, in short, President Johnson’s policy now became supreme, till Hancock himself was relieved in March, 1868.

My official connection with the reconstruction of Louisiana and Texas practically closed with this order concerning the jury lists. In my judgment this had become a necessity, for the disaffected element, sustained as it was by the open sympathy of the President, had grown so determined in its opposition to the execution of the Reconstruction acts that I resolved to remove from place and power all obstacles; for the summer’s experience had convinced me that in no other way could the law be faithfully administered.

The President had long been dissatisfied with my course; indeed, he had harbored personal enmity against me ever since he perceived that he could not bend me to an acceptance of the false position in which he had tried to place me by garbling my report of the riot of 1866. When Mr. Johnson decided to remove me, General Grant protested in these terms, but to no purpose:

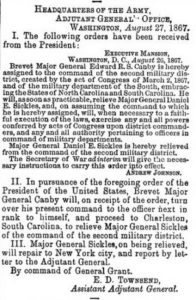

“HEADQUARTERS ARMIES OF THE UNITED STATES,

“WASHINGTON, D. C., August 17, 1867

“SIR: I am in receipt of your order of this date directing the assignment of General G. H. Thomas to the command of the Fifth Military District, General Sheridan to the Department of the Missouri, and General Hancock to the Department of the Cumberland; also your note of this date (enclosing these instructions), saying: ‘Before you issue instructions to carry into effect the enclosed order, I would be pleased to hear any suggestions you may deem necessary respecting the assignments to which the order refers.’

“I am pleased to avail myself of this invitation to urge—earnestly urge—urge in the name of a patriotic people, who have sacrificed hundreds of thousands of loyal lives and thousands of millions of treasure to preserve the integrity and union of this country—that this order be not insisted on. It is unmistakably the expressed wish of the country that General Sheridan should not be removed from his present command.

“This is a republic where the will of the people is the law of the land. I beg that their voice may be heard.

“General Sheridan has performed his civil duties faithfully and intelligently. His removal will only be regarded as an effort to defeat the laws of Congress. It will be interpreted by the unreconstructed element in the South—those who did all they could to break up this Government by arms, and now wish to be the only element consulted as to the method of restoring order—as a triumph. It will embolden them to renewed opposition to the will of the loyal masses, believing that they have the Executive with them.

“The services of General Thomas in battling for the Union entitle him to some consideration. He has repeatedly entered his protest against being assigned to either of the five military districts, and especially to being assigned to relieve General Sheridan.

“There are military reasons, pecuniary reasons, and above all, patriotic reasons, why this should not be insisted upon.

“I beg to refer to a letter marked ‘private,’ which I wrote to the President when first consulted on the subject of the change in the War Department. It bears upon the subject of this removal, and I had hoped would have prevented it.

“I have the honor to be, with great respect, your obedient servant,

“U. S. GRANT,

“General U. S. A., Secretary of War ad interim.

“His Excellency A. JOHNSON,

“President of the United States.”

I was ordered to command the Department of the Missouri (General Hancock, as already noted, finally becoming my successor in the Fifth Military District), and left New Orleans on the 5th of September. I was not loath to go. The kind of duty I had been performing in Louisiana and Texas was very trying under the most favorable circumstances, but all the more so in my case, since I had to contend against the obstructions which the President placed in the way from persistent opposition to the acts of Congress as well as from antipathy to me—which obstructions he interposed with all the boldness and aggressiveness of his peculiar nature.

On more than one occasion while I was exercising this command, impurity of motive was imputed to me, but it has never been truthfully shown (nor can it ever be) that political or corrupt influences of any kind controlled me in any instance. I simply tried to carry out, without fear or favor, the Reconstruction acts as they came to me. They were intended to disfranchise certain persons, and to enfranchise certain others, and, till decided otherwise, were the laws of the land; and it was my duty to execute them faithfully, without regard, on the one hand, for those upon whom it was thought they bore so heavily, nor, on the other, for this or that political party, and certainly without deference to those persons sent to Louisiana to influence my conduct of affairs.

Some of these missionaries were high officials, both military and civil, and I recall among others a visit made me in 1866 by a distinguished friend of the President, Mr. Thomas A. Hendricks. The purpose of his coming was to convey to me assurances of the very high esteem in which I was held by the President, and to explain personally Mr. Johnson’s plan of reconstruction, its flawless constitutionality, and so on. But being on the ground, I had before me the exhibition of its practical working, saw the oppression and excesses growing out of it, and in the face of these experiences even Mr. Hendricks’s persuasive eloquence was powerless to convince me of its beneficence. Later General Lovell H. Rousseau came down on a like mission, but was no more successful than Mr. Hendricks.

During the whole period that I commanded in Louisiana and Texas my position was a most unenviable one. The service was unusual, and the nature of it scarcely to be understood by those not entirely familiar with the conditions existing immediately after the war. In administering the affairs of those States, I never acted except by authority, and always from conscientious motives. I tried to guard the rights of everybody in accordance with the law. In this I was supported by General Grant and opposed by President Johnson. The former had at heart, above every other consideration, the good of his country, and always sustained me with approval and kind suggestions. The course pursued by the President was exactly the opposite, and seems to prove that in the whole matter of reconstruction he was governed less by patriotic motives than by personal ambitions. Add to this his natural obstinacy of character and personal enmity toward me, and no surprise should be occasioned when I say that I heartily welcomed the order that lifted from me my unsought burden.

Harriet Beecher Stowe agreed with General Grant that Philip Sheridan did a good job in the Fifth District. In her 1868 book she said that Sheridan’s prior rule over a Native-American tribe was a lot like running an “unreconstructed” rebel city. From Men of Our Times or Leading Patriots of The Day (pages 418-419):

General Sheridan’s administration as military governor at New Orleans, was a surprise to his friends, from its exhibition of broad and high administrative qualities. Yet there is much that is alike in the abilities of a good general and a good ruler. Gen. Grant is a very wise judge of men, and his brief and characteristic record of his estimate of Sheridan might419 have justified hopes equal to the actual result. To any one remembering also his early days of authority over the Yokimas in Oregon, it would doubtless have done so; for a Yokima community and the community of an “unreconstructed” southern rebel city are a good deal alike in many things. What Grant said of Sheridan was as follows, and was sent to Secretary Stanton just after Cedar Creek, and a little while before Sheridan’s appointment as Major-General in the Regular Army, in place of McClellan, resigned:

“City Point, Thursday, Oct. 20, 8 p. m.

Hon. E. M. Stanton, etc.:

I had a salute of one hundred guns from each of the armies here fired in honor of Sheridan’s last victory. Turning what bid fair to be a disaster into a glorious victory, stamps Sheridan what I always thought him, one of the ablest of generals.

U. S. Grant, Lieutenant-General.”

The extraordinary series of popular ovations which have attended Sheridan’s recent tour through part of the North, have proved that he is profoundly admired, honored and loved by all good citizens; and unless we except Grant, probably Sheridan is the most popular—and deservedly the most popular—of all the commanders in the war. Such a popularity, and won not by words but by deeds, is an enviable possession.

![Tennessee. ([S.l.], 1826.; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2003627038/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/tn-300x188.jpg)