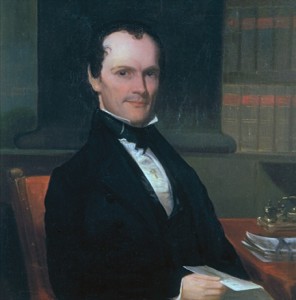

James Fisher Robinson, governor of the border State of kentucky, opposed President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. The following editorial wonders how this could be. Kentucky has lots of troops in the Union military (in fact, “In January 1863, Governor Robinson proudly noted that a divided Kentucky at that time had provided over 44,000 men to aid the Union.” The The Times thinks it is because “no public man or public journal” has been courageous enough to speak out against slavery. Also, Kentucky might be more sensitive about the issue because it has more slaves than the border states Maryland and Missouri combined, although that would mean Kentucky slave-owners would benefit more by a proposed compensated emancipation scheme.

From The New-York Times January 13, 1863:

Kentucky and Emancipation.

What means this terrible eruption of wrath from the Kentucky Governor against the President’s Proclamation? What are we to make of the constant fulminations of the Kentucky senators and Representatives at Washington against the Executive policy? How happens it that of the three slaveholding Border States, Maryland, Missouri and Kentucky, the last alone should be kindled into rage? Missouri, five years ago, was as extreme in its devotion to Slavery as South Carolina itself, and even more furious. Its slave population, in the decade between 1850 and 1860, increased thirty-one and a half per cent., while that of Kentucky increased less than seven per cent. And yet we find Missouri promptly and cordially endorcing the emancipation propositions of the President, by a large majority of its popular vote. We see, too, the leading men of Maryland, and the ablest portion of its Press, taking the same bold stand; and there is no longer a question that the State will, not long hence, concur formally in the plan of compensated emancipation. If Gov. GAMBLE and Gov. BRADFORD can yield so pleasantly to the new necessities of the day, why should Gov. ROBINSON storm so fearfully? If the present Congressmen from Missouri and Maryland, opposed to emancipation as most of them personally are, can submit with such quiet grace to the new policy, why should the neighbors and followers of HENRY CLAY — the great Kentuckian, who always declared Slavery to be a great misfortune to Kentucky — why, we ask, should Mr. WICKLIFFE and his colleagues blaze with such indignation because the Government has at last opened a way by which their State may be cleared of Slavery? What peculiar principle or interest has Kentucky in the matter, that Missouri and Maryland have not?

We know that it is often said, and sometimes even upon the floor of Congress, that the peculiar conduct of Kentucky is owing to feeble loyalty. We do not believe it. Kentucky is every whit as loyal as either of the other two States. It has had more men in active military service for the Union than either of them — no less than forty-one regiments; and no National troops have fought with greater gallantry, as Shiloh and Donelson and Murfreesboro can well testify. The Kentucky Generals Anderson, Rousseau, Crittenden, Nelson, Boyle and others have done deeds for the old flag that will ever live in history. We have not a doubt that the Kentucky Representative who declared, last Friday, on the floor of the House that Kentucky was “as loyal and true as any State in the Union,” spoke the exact truth, if by the State he meant the majority of its people. They are unquestionably — as he said he was — “for this Government first, last and forever.” That thing was tested over and over again at the polls, and afterward by MORGAN’s appeals on his raids, and BRAGG’s proclamations during his great invasion, in a manner that has made fair doubt no longer possible. It will not do to attribute to disloyalty this peculiar hostility of Kentucky to the Emancipation policy.

The real reason probably may be found in two causes. First, Kentucky has more slaves than both the other States combined — her figure, by the last census, being 225,483, while that of Missouri was 114,931, that of Maryland 87,189. Having more property bound up in the system, it is natural that she should be more sensitive about it. But a more important cause for this difference of conduct on the part of Kentucky has been the fact that, while Missouri has had such public leaders as Senator HENDERSON and GRATZ BROWN, and Maryland such public journals as the Baltimore American and the Cambridge Intelligencer, to advocate the emancipation policy with ability and unflagging zeal, there has been in Kentucky no public man or public journal bold enough to start the discussion on the Anti-Slavery side. There is not a politician or a political organ in Kentucky that is not as timid as a hare on any question bearing against Slavery. The old habit of tabooing all discussion on the subject still prevails. A single high-souled, independent, earnest man of ability might easily break this up. The discussion once fairly opened, there can be no doubt it would lead to the same results as in the other two States.

If Kentucky has more slaves than they, she would obtain a proportionately larger share of compensation from the National Government. This compensation would, in fact, be just so much gained. The politicians of Kentucky seem to us to err in taking it for granted that the question still is whether Slavery shall be perpetuated in the State on its old basis, and in its old character. That thing, whether they accept the President’s plan or not, is impossible. Gen. ROSECRANS was perfectly right in declaring as he did, at the public banquet given in his honor at Louisville, last Summer, that if the war went on, Slavery must come to an end. Proclamation or no Proclamation, it is an institution that cannot stand the shock of civil war. All accounts agree that everywhere within our army lines effective slave labor is rapidly coming to an end. This is an inevitable result of the disordered condition of society. The slaves are becoming practically free by the mere force of circumstances. When this point is once reached, they never can be put back into their old condition with any profit to their masters. They will be so “demoralized,” as the expression is, that as slaves they will be forever worthless. Even apart from this inevitable operation of the war, how could Kentucky expect to retain Slavery when surrounded by Free States on every side but the South, as she would be when the system is at an end in Missouri and Western Virginia? It would cost her intolerable trouble.

The extinction of Slavery in Kentucky is simply a question of manner and time. Could the discussion once be fairly started among the people of the State, we are confident that the decision would be, as in Missouri and Maryland, that the compensating scheme of the President is the right manner, and now the appropriate time. But if the State chooses to shirk the subject, until her slaves become a profitless burden, without marketable value, she certainly should be allowed the privilege, without molestation. Of course if she resists until then, she will not expect help from the Government. That which has merely a nominal value can never be paid for in National money. Spurning the Government offer now, she must not complain when circumstances finally compel her to part from her cherished institution without a dollar from the Government treasury to lighten the sacrifice. There is a clear privilege on both sides; and there should be passion on neither.

The influence of the press and federal money.

Compensated emancipation only became law in the United States in the District of Columbia (April 16, 1862).

Wikipedia

attributes the following to Governor Robinson:

…he lamented what he perceived as poor treatment of the state as disloyal by the Federal government. He cited examples such as the declaration of martial law in the Commonwealth and the suspension of the right of habeas corpus for its citizens. He answered President Lincoln’s contention “that military necessity is not to be measured by Constitutional limits” by warning “If military necessity is not to be measured by Constitutional limits, we are no longer a free people.”

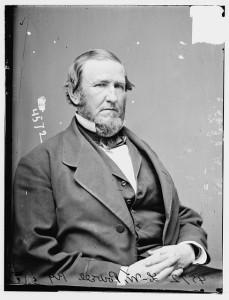

Lazarus Whitehead Powell served as U.S. senator from 1859-65:

Senator Powell favored Kentucky’s neutrality policy during the Civil War, but nationally, the conflict put him in a tenuous political situation. On one hand, he was a favored a strong national government and a strict interpretation of the U.S. Constitution. On the other hand, he was an opponent of coercion, and due to Kentucky’s proximity to the Southern states, maintained a more sympathetic view of the southern cause that legislators from more northern states. During his term as governor, Powell had been critical of Northern states that refused to abide by the Fugitive Slave Act.

In 1861, Senator Powell vigorously condemned President Lincoln’s decision to suspend the writ of habeas corpus. In 1862, he denounced the arrest of some citizens of Delaware—officially, the arrests were called “resolutions of inquiry”—as a violation of constitutional rights. These stances led to calls for his resignation by the Kentucky General Assembly in 1861, and some of his colleagues, led by Kentucky’s other senator, Garrett Davis, unsuccessfully attempted to have him expelled from the Senate. Before the end of the war, both the General Assembly and Davis admitted being wrong in their attempts to remove him.