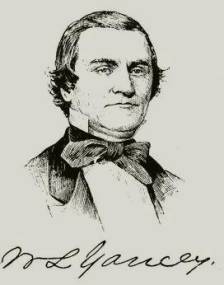

The famous fire-eater, William L. Yancey, died of kidney disease at his home in Montgomery, Alabama on July 27, 1863.

From the Richmond Daily Dispatch August 1, 1863:

The late William L Yancey.

The death of William L. Yancey, Confederate Senator from Alabama, is an event that occasions much public regret. He was among the most devoted of the sons of the South to the cause of the South, as he was one of its ablest defenders. He is conceded generally to have been the most brilliant man in the Confederate Senate, as he was the most chaste and eloquent orator in the South. Though we must all deplore the loss of leaders in our struggle, we may be assured that the cause itself will bring out more than enough to fill their places, for the times must be fruitful of great men.

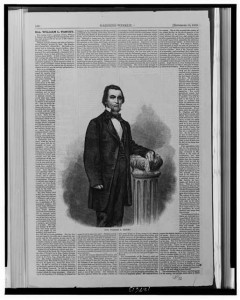

From Harper’s Weekly August 22, 1863:

YANCEY.

WILLIAM L. YANCEY is a man who will be known in our history as one of the most virulent but not one of the most able of the traitors who have conspired for the ruin of their country. …

Mr. Yancey himself furnished an illustration of the absurdity of his own dogmas. Every society is truly prosperous because secure in the degree that it allows the most liberal discussion. In any truly free community whatever can not be debated ought not to be endured, because such a community is governed by public opinion, and without discussion public opinion is unenlightened. During the last Presidential canvass Mr. Yancey made a tour of the free States for the purpose of persuading the people that they had better not vote against the slaveholders upon pain of summary ruin. In States made prosperous and happy by a greater individual freedom than was ever known Mr. Yancey stood before the people to cajole and threaten them from the exercise of political rights. He was heard and endured, and sometimes applauded. But the fact that he was heard and was tolerated in free States while he advocated shivery, showed the infinitely higher political civilization of those States than that which Mr. Yancey advocated, and to which he was accustomed. To plead for liberty in those States would have cost the orator his life. …

But although the “revolution” is in its third year, Mr. Yancey had achieved no more renown in it than he did before it began. He went to Europe as an emissary to make the thing look respectable, but soon returned disheartened. Since then he has been ex officio, as a “Senator,” one of the ring-leaders of the rebellion. But his name was never heard. His influence has nowhere appeared. Like Toombs, Wigfall, Ellett, Spratt, Keitt, and Orr, his sole distinction is that he hated his country, because his country loved liberty.

As a “Senator”, Yancey still had some fire:

In Congress, Yancey and Benjamin Hill of Georgia, who had previously clashed in 1856, had their differences over a bill intended to create the Confederate Supreme Court erupt into physical violence. Hill hit Yancey in the head with a glass inkstand on the floor of the Senate, but in the ensuing investigation it was Yancey, not Hill, who was censured.

Yancey died under the Confederate national flag that was adopted May 1, 1863, which eventually “became criticized for being ‘too white’.” It could be mistaken as a flag of truce.

I reacted to the Harper’s story by thinking there sure was less liberty in the North after the rebellion started. Where does legitimate criticism of a regime end and treason begin?