From the Richmond Daily Dispatch September 13, 1864:

M’Clellan’s letter of Acceptance — he is for the Union as the only basis for peace.

The following is the letter of General McClellan to the committee announcing his nomination for the Yankee Presidency by the Chicago Convention:

Orange, New Jersey, September 8, 1864.

Gentlemen:

I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your letter informing me of my nomination by the Democratic National Convention, recently assembled at Chicago, as their candidate at the next election for President of the United States.

It is unnecessary for me to say to you that this nomination comes to me unsought. I am happy to know that, when the nomination was made, the record of my public life was kept in view.

The effect of long and varied service in the army, during war and peace, has been to strengthen and make indelible in my mind and heart the love and reverence for the Union, Constitution, laws and flag of our country, impressed upon me in early youth. These feelings have thus for guided the course of my life, and must continue to do so to its end.

The existence of more than one government over the region our flag is incompatible with the and the happiness of the people.

The preservation of our Union was the sole avowed object for which the war was commenced. It should have been conducted for that object only, and in accordance with those principles which I took occasion to declare when in active service.

Thus conducted, the work of reconciliation would have been easy, and we might have reaped the benefits of our many victories on land and sea.

The Union was originally formed by the exercise of a spirit of conciliation and compromise: To restore and preserve it, the same spirit must prevail in our councils and in the hearts of the people. The re-establishment of the Union in all its integrity is, and must continue to be, the indispensable condition in any settlement. So soon as it is clear, or even probable, that our present adversaries are ready for peace upon the basis of the Union, we should exhaust all the resource of statesmanship practiced by civilized nations, and taught by the traditions of the American people, consistent with the honor and interest of the country, to secure such peace, re-establish the Union, and guarantee for the future the constitutional rights of every State. The Union is the one condition of peace; we ask no more.

Let me add, what I doubt not was, although unexpressed, the sentiment of the convention; as it is of the people they represent, that when any one State is willing to return to the Union, it should be received at once, with a full guarantee of all its constitutional rights.

If a frank, earnest, and persistent effort to obtain these objects should fail, the responsibility for ulterior consequences will fall upon these who remain in arms against the Union; but the Union must be preserved at all hazards.

I could not look in the face of my gallant comrades of the army and navy, who have survived so many bloody battles, and tell them that their labors and the sacrifice of so many of our slain and wounded brethren had been in vain — that we had abandoned that Union for which we have so often periled our lives. A vast majority of our people, whether in the army and navy or at home, would, as I would, hail with unbounded joy the permanent restoration of peace on the basis of the Union, under the Constitution without the effusion of another drop of blood, But no peace can be permanent without union.

As to the other subjects presented in the resolutions of the convention, I need only say that I should seek in the Constitution of the United States, and the laws framed in the ordnance therewith, the rule of my duty and the limitations of executive power; endeavor to restore economy in the public expenditures, re-establish the supremacy of law, and, by the operation of a more vigorous nationality, resume our commanding position among the nations of the earth.

The condition of our finances, the depreciation of the paper money, and the burden thereby imposed on labor and capital, show the necessity of a return to a sound, financial system; while the rights of citizens and the rights of States, and the binding authority of law over President, army and people, are subjects of not less vital importance in war than in peace. Believing that the views here expressed are those of the convention and the people you represent, I accept the nomination.

I realize the weight of the responsibility to be borne should the people ratify your choice. Conscious of my own weakness, I can only seek fervently the guidance of the Ruler of the Universe, and, relying on His all-powerful aid, do my best to restore union and peace to a suffering people, and to establish and guard their liberties and rights.

I am, gentlemen, very respectfully,

Your obedient servant,

George B. McClellan.

Hon. Horatia Seymour and others, Committee.

Southerners might not have liked General McClellan’s statement that peace required the restoration of the Union because the war was going to drag on, apparently. Pro-administraton journals saw hypocrisy in the general accepting the nomination and presumably running on a Copperhead inspired platform. Here’s an example from the September 24, 1864 issue of Harper’s Weekly (at Son of the South):

SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 24, 1864.

McCLELLAN’S LETTER.

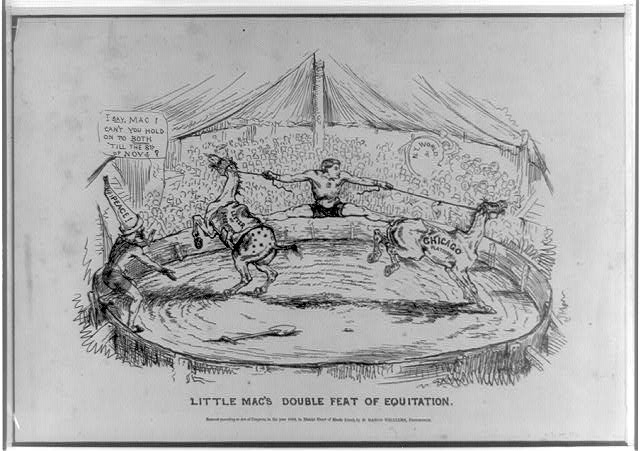

GENERAL McCLELLAN may be a good rider, but it requires an extraordinary exercise of the skill of the most accomplished equestrian simultaneously to ride two horses going different ways. The chance is that he will fall between the two. His letter of acceptance is a worthy conclusion to the ignominious performance at Chicago. It is confused and verbose: wanting both the manly directness of the soldier and the earnest conviction of the patriot.

He begins by saying that the nomination was ” unsought,” and that the Convention knew it. If it did, it had a monopoly of the knowledge; for if there has been one fact perfectly evident in our late history, it is that General McCLELLAN, from the time he was placed in command of the Army of the Potomac, has, under careful advice and management, been aiming at this nomination. His remark is entirely superfluous, and shakes at the very beginning the confidence of every reader. …[much more]

James M. McPherson wrote that General McClellan originally considered an acceptance letter that “endorsed an armistice qualified only by a proviso calling for renewal of the war if negotiations failed to produce reunion.” Some of his advisers convinced him that it would be impossible to crank up the war machine again once an armistice was in place – “an armistice without conditions would mean surrender of the Union. After Atlanta such a proposal would stultify his candidacy.”[1]

You can read about the following political cartoon at the Library of Congress

- [1]McPherson, James M. The Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York: Ballantine Books, 1989. Print. page 775.↩