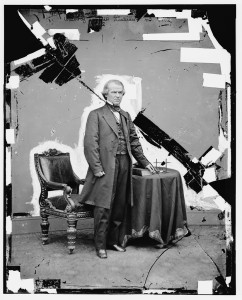

In early December 1865 the 39th Congress convened and President Andrew Johnson sent the legislators his first annual message. A newspaper in Gotham was well-satisfied with the President’s report.

From The New-York Times December 6, 1865:

The President’s Message.

Probably no Executive document was ever awaited with greater interest than the Message transmitted to Congress yesterday. It is safe to say that none ever gave greater satisfaction when received. Its views, on the most momentous subjects, domestic and foreign, that ever concerned the nation, are full of wisdom, and are conveyed with great force and dignity.

In regard to reconstruction, the President begins by defining with great clearness the mutual relations of the constitution and the States. He shows that each is vital to the other, and that the theory that States can be extinguished would be fatal to the constitution. The military rule over the insurrectionary States was an exceptional condition, imposed by necessity, and is to be terminated just as soon as those States can be brought again into a harmonious working with the National Government For this end the government has diligently labored, and with such success, as the President believes, that now nothing remains to be done by the late erring States but the ratification of the Constitutional Amendment forever prohibiting slavery, as a pledge of perpetual loyalty and peace. It will then be for Congress to consummate the restoration by admitting the Southern Senators and Representatives who, in its high judgment, possess the necessary qualifications.

In regard to punishment for treason, the President urges the adoption of measures for the early resumption of all the functions of the Circuit Courts in the South, so as to secure impartial trials, and vindicate the principle that treason is a crime to be punished, and forever settle that no State has power to relieve its citizens of their obligations to the Union.

In regard to the freedmen, the President declares that the constitution gives the general government no power to prescribe the qualifications of the electors in the various States; yet he is free to recognize in the broadest terms its duty, in good faith, to take care that the freedmen should be secure in their liberty and their property, and their right to labor and a just return for their labor.

The President sets forth the unjust conduct of England in the war with great point, and yet with an entire avoidance of all calculated to irritate. His manner of treating it can hardly fail to rouse a feeling of shame in every manly British bosom. He advises no unfriendly resorts to obtain redress, but to wait patiently for the recognition of justice.

In respect to the foreign establishment of monarchy in Mexico, the President contents himself with affirming that the system of noninterference and mutual abstinence from propagandism is the true rule for the two hemispheres. He avoids all language having any appearance of menace, and believes that our principles have a moral force that must soon command acceptance. The correspondence between France on the subject, it is mentioned, will be laid before Congress “at the proper time.”

The Message [cl]osed with a brief but very impressive retrospect of the way in which our institutions have vindicated themselves from their first establishment, and with a recognition of the wonderful manner in which Providence has protected and magnified the nation. The whole document is one of which every American may well be proud, for its elevation of tone, its practical wisdom and its quiet exhibition of the national strength and glory. It will be admired not only at home, but cannot fail of making a most favorable impression all over the civilized world.