In late November 1867 the 40th United States Congress reconvened after about a four months’ absence. In his Third Annual Message, which he sent over to the Capitol on December 3rd, the president didn’t exactly welcome Congress back to town. In a major section of his report, Mr. Johnson emphasized that the Congressional Reconstruction laws enacted earlier in 1867 were not working, were dangerous, and should be repealed.

In its December 4th editorial commenting on the president’s message, The New-York Times strongly criticized the message as being too arrogant, bitter, and hostile to promote the peace and harmony of the nation and its component parts. President Johnson didn’t provide Congress with any information about problems with the Reconstruction Acts as they were being implemented or suggest any well thought out changes that would improve laws’ implementation. Instead he regurgitated the same arguments he used in his veto messages – but the laws were already in force. The president’s approach would “widen the breach” between the two branches.

The newspaper believed that Congress would find the following passage especially threatening (from Project Gutenberg):

How far the duty of the President “to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution” requires him to go in opposing an unconstitutional act of Congress is a very serious and important question, on which I have deliberated much and felt extremely anxious to reach a proper conclusion. Where an act has been passed according to the forms of the Constitution by the supreme legislative authority, and is regularly enrolled among the public statutes of the country, Executive resistance to it, especially in times of high party excitement, would be likely to produce violent collision between the respective adherents of the two branches of the Government. This would be simply civil war, and civil war must be resorted to only as the last remedy for the worst of evils. Whatever might tend to provoke it should be most carefully avoided. A faithful and conscientious magistrate will concede very much to honest error, and something even to perverse malice, before he will endanger the public peace; and he will not adopt forcible measures, or such as might lead to force, as long as those which are peaceable remain open to him or to his constituents. It is true that cases may occur in which the Executive would be compelled to stand on its rights, and maintain them regardless of all consequences. If Congress should pass an act which is not only in palpable conflict with the Constitution, but will certainly, if carried out, produce immediate and irreparable injury to the organic structure of the Government, and if there be neither judicial remedy for the wrongs it inflicts nor power in the people to protect themselves without the official aid of their elected defender–if, for instance, the legislative department should pass an act even through all the forms of law to abolish a coordinate department of the Government–in such a case the President must take the high responsibilities of his office and save the life of the nation at all hazards. [The editorial appears to have added the italics.]

At least in this particular editorial the Times didn’t specifically mention what seems the most striking part of the message from the perspective of 150 years later – the president’s views on the political place of black people. The message includes over 2000 words about the ex-slaves’ political rights in the South and the impact on the nation as a whole. Here are parts of that section. Mr. Johnson segues from his denunciation of the Reconstruction Acts to his fear of black supremacy:

It is manifestly and avowedly the object of these laws to confer upon Negroes the privilege of voting and to disfranchise such a number of white citizens as will give the former a clear majority at all elections in the Southern States. This, to the minds of some persons, is so important that a violation of the Constitution is justified as a means of bringing it about. The morality is always false which excuses a wrong because it proposes to accomplish a desirable end. We are not permitted to do evil that good may come. But in this case the end itself is evil, as well as the means. The subjugation of the States to Negro domination would be worse than the military despotism under which they are now suffering. It was believed beforehand that the people would endure any amount of military oppression for any length of time rather than degrade themselves by subjection to the Negro race. Therefore they have been left without a choice. Negro suffrage was established by act of Congress, and the military officers were commanded to superintend the process of clothing the Negro race with the political privileges torn from white men.The blacks in the South are entitled to be well and humanely governed, and to have the protection of just laws for all their rights of person and property. If it were practicable at this time to give them a Government exclusively their own, under which they might manage their own affairs in their own way, it would become a grave question whether we ought to do so, or whether common humanity would not require us to save them from themselves. But under the circumstances this is only a speculative point. It is not proposed merely that they shall govern themselves, but that they shall rule the white race, make and administer State laws, elect Presidents and members of Congress, and shape to a greater or less extent the future destiny of the whole country. Would such a trust and power be safe in such hands?

The peculiar qualities which should characterize any people who are fit to decide upon the management of public affairs for a great state have seldom been combined. It is the glory of white men to know that they have had these qualities in sufficient measure to build upon this continent a great political fabric and to preserve its stability for more than ninety years, while in every other part of the world all similar experiments have failed. But if anything can be proved by known facts, if all reasoning upon evidence is not abandoned, it must be acknowledged that in the progress of nations Negroes have shown less capacity for government than any other race of people. No independent government of any form has ever been successful in their hands. On the contrary, wherever they have been left to their own devices they have shown a constant tendency to relapse into barbarism. In the Southern States, however, Congress has undertaken to confer upon them the privilege of the ballot. Just released from slavery, it may be doubted whether as a class they know more than their ancestors how to organize and regulate civil society. Indeed, it is admitted that the blacks of the South are not only regardless of the rights of property, but so utterly ignorant of public affairs that their voting can consist in nothing more than carrying a ballot to the place where they are directed to deposit it. I need not remind you that the exercise of the elective franchise is the highest attribute of an American citizen, and that when guided by virtue, intelligence, patriotism, and a proper appreciation of our free institutions it constitutes the true basis of a democratic form of government, in which the sovereign power is lodged in the body of the people. A trust artificially created, not for its own sake, but solely as a means of promoting the general welfare, its influence for good must necessarily depend upon the elevated character and true allegiance of the elector. It ought, therefore, to be reposed in none except those who are fitted morally and mentally to administer it well; for if conferred upon persons who do not justly estimate its value and who are indifferent as to its results, it will only serve as a means of placing power in the hands of the unprincipled and ambitious, and must eventuate in the complete destruction of that liberty of which it should be the most powerful conservator. I have therefore heretofore urged upon your attention the great danger–to be apprehended from an untimely extension of the elective franchise to any new class in our country, especially when the large majority of that class, in wielding the power thus placed in their hands, can not be expected correctly to comprehend the duties and responsibilities which pertain to suffrage. Yesterday, as it were, 4,000,000 persons were held in a condition of slavery that had existed for generations; to-day they are freemen and are assumed by law to be citizens. It can not be presumed, from their previous condition of servitude, that as a class they are as well informed as to the nature of our Government as the intelligent foreigner who makes our land the home of his choice. In the case of the latter neither a residence of five years and the knowledge of our institutions which it gives nor attachment to the principles of the Constitution are the only conditions upon which he can be admitted to citizenship; he must prove in addition a good moral character, and thus give reasonable ground for the belief that he will be faithful to the obligations which he assumes as a citizen of the Republic. Where a people–the source of all political power–speak by their suffrages through the instrumentality of the ballot box, it must be carefully guarded against the control of those who are corrupt in principle and enemies of free institutions, for it can only become to our political and social system a safe conductor of healthy popular sentiment when kept free from demoralizing influences. Controlled through fraud and usurpation by the designing, anarchy and despotism must inevitably follow. In the hands of the patriotic and worthy our Government will be preserved upon the principles of the Constitution inherited from our fathers. It follows, therefore, that in admitting to the ballot box a new class of voters not qualified for the exercise of the elective franchise we weaken our system of government instead of adding to its strength and durability.

I yield to no one in attachment to that rule of general suffrage which distinguishes our policy as a nation. But there is a limit, wisely observed hitherto, which makes the ballot a privilege and a trust, and which requires of some classes a time suitable for probation and preparation. To give it indiscriminately to a new class, wholly unprepared by previous habits and opportunities to perform the trust which it demands, is to degrade it, and finally to destroy its power, for it may be safely assumed that no political truth is better established than that such indiscriminate and all-embracing extension of popular suffrage must end at last in its destruction. I repeat the expression of my willingness to join in any plan within the scope of our constitutional authority which promises to better the condition of the Negroes in the South, by encouraging them in industry, enlightening their minds, improving their morals, and giving protection to all their just rights as freedmen. But the transfer of our political inheritance to them would, in my opinion, be an abandonment of a duty which we owe alike to the memory of our fathers and the rights of our children. …

The great interests of the country require immediate relief from these enactments. Business in the South is paralyzed by a sense of general insecurity, by the terror of confiscation, and the dread of Negro supremacy. The Southern trade, from which the North would have derived so great a profit under a government of law, still languishes, and can never be revived until it ceases to be fettered by the arbitrary power which makes all its operations unsafe. That rich country–the richest in natural resources the world ever saw–is worse than lost if it be not soon placed under the protection of a free constitution. Instead of being, as it ought to be, a source of wealth and power, it will become an intolerable burden upon the rest of the nation.

In the fall of 1867 the NY Times headlined many of its front pages “TELEGRAMS.”, maybe in an attempt to be as much like CNN as possible 150 years ago. It didn’t take too long for a succinct reaction to the annual message from England. From The New-York Times December 6, 1867:

THE PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE.

____

View of the British Press – Distrust in Financial Circles.

LONDON, Thursday, Dec. 5 – Noon.

Copious extracts from the message of President JOHNSON, which were received by Cable, are published here to-day. In commenting the Times has the following:

“The message shows that Mr. JOHNSON has learned nothing. He transcends himself in imprudence. He regards his office as absolute sovereigns do their prerogatives. He forfeits all respect. It is hard to say where the hope of the people of the United States lies between JOHNSON on the one side and STEVENS on the other.”

The other journals use similar language on the subject.

The reference in the President’s Message to the Alabama claims, coupled with Lord STANLEY’S dispatch to Mr. FORD on the same subject, has created considerable distrust in financial circles.

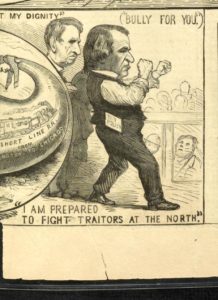

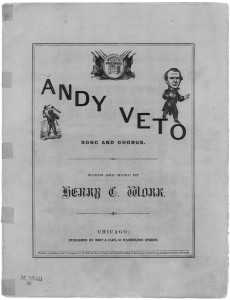

![The operations of the registration laws and Negro [suffr]age in the South / from sketches by James E. Taylor. ( Illus. in: Frank Leslie's illustrated newspaper, 1867 Nov. 30, pp. 168-169. ; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/96513248/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Maconregistrationn-300x197.jpg)

![The operations of the registration laws and Negro [suffr]age in the South / from sketches by James E. Taylor. ( Illus. in: Frank Leslie's illustrated newspaper, 1867 Nov. 30, pp. 168-169. ; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/96513248/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/political-debate-253x300.jpg)