On February 22, 1868 the United States House of Representatives began debating its Reconstruction Committee’s report recommending the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson. After a Sabbath Day’s rest the debate resumed on Monday the 24th. By 6:00 PM the full House had voted to impeach the United States president for the first time since the Constitution had come into effect almost four score years before. A correspondent touched on the historical significance and detailed the change in the Republican majority.

From The New-York Times February 25, 1868:

Special Dispatches to the New-York Times.

WASHINGTON, Monday, Feb.24.

The first act in the great civil drama of the nineteenth century is concluded. ANDREW JOHNSON, President of the United States, stands impeached of “high crimes and misdemeanors.” It is of no use to argue whether his acts were right or wrong, whether the law he violated is constitutional or otherwise, or whether it is good or bad policy to proceed to this extreme. The House of Representatives, with a full realization of all the possible consequences, has solemnly decided that he shall be held to account in the manner prescribed by the Constitution for his alleged misdemeanors, and, be the result what it may, the issue is made. It must be met without delay, and the first step is already complete.

That the feeling here continues profoundly deep is evidenced by the grave character and solemn dignity of the proceedings of the House to-day. The unanimity of the Republican strength on this subject is one of the most surprising developments. Heretofore, there has been a majority of the Republicans in the House strongly opposed to appealing to the last resort, and it has been twice defeated. But the feeling now is that twice have they desisted, and thrice has the President accepted it as a special immunity from punishment on which he could rely. And now, regretting its necessity as much as ever, they accept the last resort as a stern but disagreeable duty, simply because magnanimity is no longer a virtue, and conciliation no longer a policy with a man who not only betrayed his party, but stops not even before his country’s peril. Such is their feeling; and they are ready not only to carry the issue through the Senate, but to that tribunal which is to give the final verdict – the American people.

THE SCENE IN THE HOUSE.

That the events now transpiring here are without precedent in many respects, and that such scenes are not likely to occur again in the lifetime of any, seems to be fully appreciated by the people, resident and transient, of this city. AS early as 8 o’clock this morning, two hours before the House met, spectators began to wend their way to the galleries, and in an hour they were full to overflowing; and if three thousand were seated, at least ten thousand were turned away, unable to obtain admission. This was owing in a great measure to that fact that on Saturday there had been so much overcrowding that complaints had gone to the Speaker from the privileged classes, and some cold-blooded members insisted on the rigid enforcement of the rules, which was done, without fear or favor, or distinction of any kind, and without relaxation, until the last hour of the day, when the great crush of snow-bound femininity – for it snowed all day – overflowed just the least on to the sacred precincts of the chamber of the House. The crowd in all parts of the Capitol was immense, and the early comers stood and sat their ground, eating their lunches during some dull speaker’s tirade, and never leaving until the great final vote was announced. The best of order prevailed, however, enforced by the regular Capitol police. A squad of fifty of the city Metropolitans were on hand in the rotunda, to aid, if necessary, it having been telegraphed from Philadelphia that several hundred armed roughs, under the lead of a notorious rowdy and Alderman, had left that city for the purpose of intimidating Congress. But they did not come, and there was neither violence, passion nor anger exhibited anywhere. …

________________________________________________

[The debate lasted from about 10:00 in the morning until just before 5:00 PM with the conclusion of a speech by Thaddeus Stevens.]

His voice failed him before he had uttered his first sentence, and he tremblingly asked that the Clerk might be allowed to read the manuscript copy of his speech, which request was acceded to. At two minutes before five the reading of the speech was concluded, and the vote was at once taken on the passage of the impeachment resolution. The call of the yeas and nays proceeded amid profound stillness, and nearly every member of the House responded to his name. But twelve members being absent the result was announced. Yeas 126, nays 47. …

While these dramatic events kept the spectators at Capitol Hill spellbound, the president was quietly taking dinner with Colonel Moore [Andrew Johnson’s confidential secretary]. When news of the House vote was brought to the White House, he took it very calmly, simply remarking that he thought many of those who had voted for impeachment felt more uneasy over the position in which they had put themselves than he did in the one in which they had put him. As he had already told the reporter of the Washington Express earlier in the day, he was confident that “God and the American people would make all right and save our institutions.” After all, he had merely wanted to bring the matter of the Tenure of Office Act before the Supreme Court. If this argument was somewhat disingenuous – he was really interested in deciding a political question as well – it made for good reading.[1]

You can read the February 24th speech by Thaddeus Stevens at Furman University. Here’s the closing portion:

… By the sixth section of the act referred to [Tenure of Office], it is provided

“That ever removal, appointment, or employment made, had, of exercised contrary to the provisions of this act, and making, signing, sealing, countersigning, or issuing of any commission or letter of authority for or in respect to any such appointment of employment shall be deemed , and are hereby declared to be high misdemeanors and upon trial and conviction thereof every person guilty thereof shall be punished by a fine not exceeding $10,000 or by imprisonment not exceeding five years, or both said punishments, in the discretion of the court.”

Now, in defiance of this law, Andrew Johnson, on the 21st day of February, 1868, issued his commission or latter of authority to one Lorenzo Thomas, appointing him Secretary of War ad interim, and commanded him to take possession of the Department of War and to eject the incumbent, E. M. Stanton, the in lawful possession of said office. Here if this act stood alone, would be an undeniable official misdemeanor-not only a misdemeanor per se, but declared to be so by the act itself, and the party made indictable and punishable in a criminal proceeding. If Andrew Johnson escapes with bare removal from office, it he be not fined and incarcerated in the penitentiary afterward under criminal proceedings, he may thank the weakness or the clemency of Congress and not his own innocence.

We shall propose to prove on trial that Andrew Johnson was guilty of misprision of bribery by offering to General Grant, if he would unite with him in his lawless violence, to assume in his stead the penalties and to endure the imprisonment denounced by the law. Bribery is one of the offenses specifically enumerated for which the President may be impeached and removed from office. By the Constitution, article two, section two, the President has power to nominate and, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, to appoint all officers of the United States whose appointments are not therein otherwise provided for and which shall be established by law, during the recess of the Senate, by granting commissions which shall expire at the end of their next session. Nowhere, either in the Constitution or by statute, has the President power to create a vacancy during the session of the Senate and fill it without the advice and consent of the Senate, any yet, on the 21st day of February , 1868, while the Senate was in session, he notified the head of the War Department that he was removed from office and his successor ad interim appointed. Here is a plain, recorded violation of the Constitution and laws, which, if it stood alone, would make every honest and intelligent man give his vote for impeachment, The President has persevered in his lawless course through a long series of unjustifiable acts. When the so-called confederate States of America were conquered and had laid down their arms and surrendered their territory to the victorious Union the government and final disposition of the conquered country belonged to Congress alone, according to every principle of the law of nations.

Neither the Executive nor the judiciary had any right to interfere with it except so far as was necessary to control it be military rule until the sovereign power of the nation had provided for its civil administration. No power but Congress had any right to say whether ever or when they should be admitted to the Union as States and entitles to the privileges of the Constitution of the United States. And yet Andrew Johnson, with unblushing hardihood, undertook to rule them by his own power alone, to lead them into full communion with the Union; direct them what governments to erect and what constitution to adopt, and to send Representatives and Senators to Congress according to his instructions. Where admonished by express act of Congress, more than once repeated, he disregarded the warning and continued his lawless usurpation. He is since known to have obstructed the reestablishment of those governments by the authority of Congress, and has advised the inhabitants to resist the legislation Congress. In my judgment his conduct with regard to that transaction was a high-handed usurpation of power which ought long ago to have brought him to impeachment and trial and to have removed him from his position of great mischief. He has been lucky in thus far escaping through false logic and false law. But his then acts, which will on the trial be shown to be atrocious, are open to evidence of his wicked determination to subvert the laws of his country.

I trust that when we come to vote upon this question we shall remember that although it is the duty of the President to see that the laws be executed the sovereign power of the nation rests in Congress, who have been placed around the Executive as muniments to defend his rights, and as watchmen to enforce his obedience to the law and the Constitution. His oath to obey the Constitution and our duty to compel him to do it are tremendous obligation, heavier than was ever assumed by mortal rulers. We are to protect or to destroy the liberty and happiness of a mighty people, and to take care that they progress in civilization and defend themselves against every kind of tyranny. As we deal with the first great political malefactor so will be the result of our efforts to perpetuate the happiness and good government of the human race. The God of our fathers, who inspired them with the though of universal freedom, will hold up responsible for the noble institutions which they projected and expected us to carry out, This is not to by the temporary triumph of a political party, but it is to endure in its consequence until this whole continent shall be filled with a free and untrammeled people or shall be a nest of shrinking, cowardly slaves.

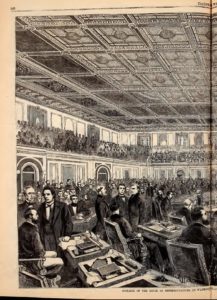

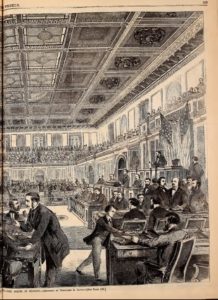

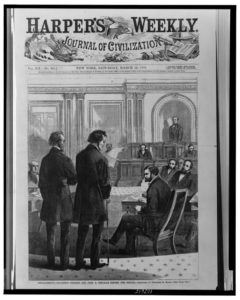

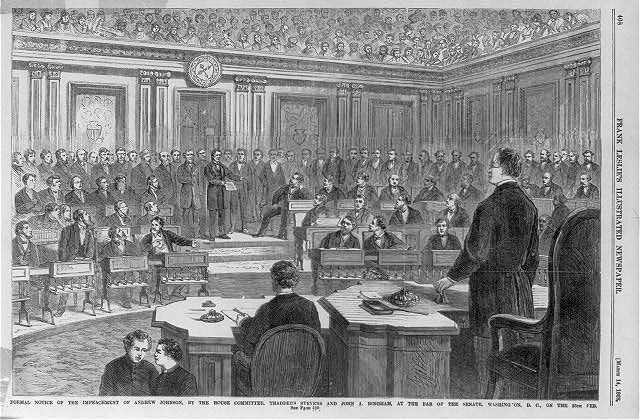

The next day Thaddeus Stevens and John A. Bingham officially informed the Senate of the House’s action.

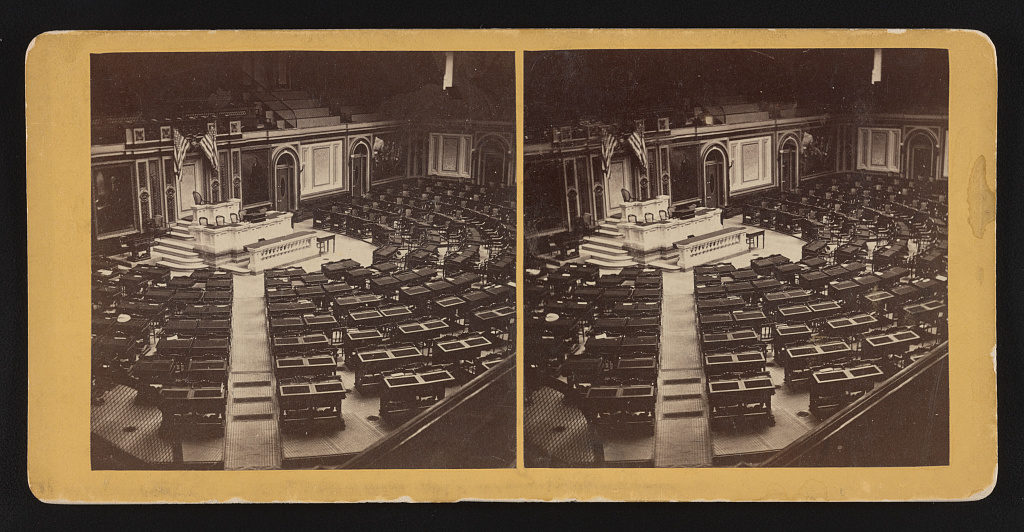

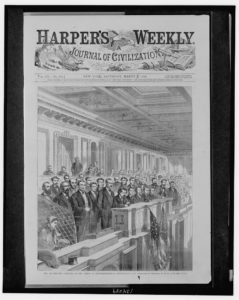

The split image of the House in session was published in the March 7, 1868 issue of Harper’s Weekly and is available at the Internet Archive (Harper’s pages 168-169). From the Library of Congress: House chamber with more information below; reporters’ gallery from the March 7, 1868 issue of Harper’s Weekly; Stevens and Bingham from the March 14, 1868 issue of Harper’s Weekly; Stevens and Bingham from the March 14, 1868 issue of Frank Leslie’s.

- [1]Trefousse, Hans L. Andrew Johnson: A Biography. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1997. Print. page 315.↩