____________

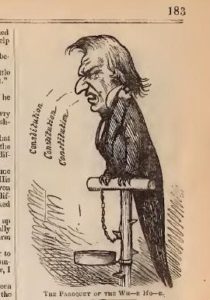

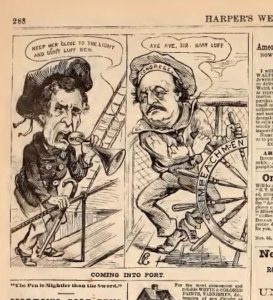

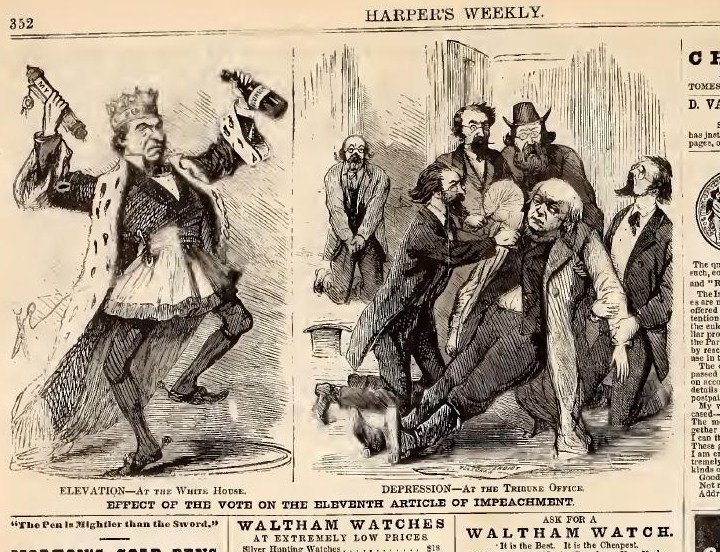

A couple cartoons in the March 21, 1868 issue of Harper’s Weekly seem to have been pointing out some irony in the struggle between Congress and Andrew Johnson. President Johnson parroted “Constitution” as the justification for his policies, for his many vetoes (mostly overridden) of the Reconstruction Acts that Congress passed. However, the Constitution was about to become his undoing – specifically its provision for impeachment of the president. After the U.S. House voted to impeach President Johnson, the Senate had been conducting his trial since March 5, 1868. To follow the letter of the Constitution regarding impeachment required strict adherence to a particular number – 2/3. As Article I, Section 3 states: “The Senate shall have the sole Power to try all Impeachments. When sitting for that Purpose, they shall be on Oath or Affirmation. When the President of the United States is tried, the Chief Justice shall preside: And no Person shall be convicted without the Concurrence of two thirds of the Members present.”

Twenty-seven states were represented by fifty-four senators in May 1868. Therefore, thirty-six was the magic number – the number of “guilty” votes necessary to convict the president. If the Senate’s vote would be a purely partisan decision, Mr. Johnson’s goose was cooked because only twelve Democrats were serving at the time. However, as the trial began to draw to a close in early May it was not at all certain that all the Republican senators would vote to convict the president, at least according to headlines in The New-York Times: On May 12th “The Final Result Considered Very Doubtful.” May 13th: “The Result Still Considered Very Uncertain.” May 14th: ‘The Conviction of the President Considered Certain.” May 15th: “The President’s Acquittal Considered Certain.” The May 16th headline knew there would be a final vote that very day and “A Senaotorial Canvass shows a Majority for Conviction.”

__________________________

On May 16th the Senate decided to vote first on the last or the Eleventh Article of Impeachment, considered a catchall, kind of summary of the first ten articles, maybe something for everyone to find some guilt. Unfortunately for the Radical Republicans seven Senators voted with all twelve Democrats against the President’s guilt on the article. 54-19=35<36

From the May 30, 1868 issue of Harper’s Weekly (page 350) (at the Internet Archive):

THE IMPEACHMENT.

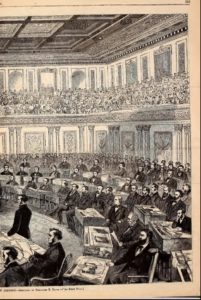

The Senate reached a vote on one of the Impeachment articles on May 16. By a resolution offered the same day it was decided that a vote should be taken on the eleventh article first. The vote was formally taken, and resulted in the acquittal of the President on that charge by a vote of 19 nays to 35 yeas. Seven Republican Senators, viz.: FESSENDEN, FOWLER, HENDERSON, ROSS, TRUMBULL, VAN WINKLE and WILLEY voted with the Democrats for acquittal. The excitement in the Senate and throughout the capital was very great. Our illustrations on page 340 are of scenes enacted in the city and Capitol during the closing hours of Impeachment.

SCENE IN THE SENATE LOBBY.

During the secret session which immediately preceded the vote the lobby of the Senate was crowded with Representative, reporters, and citizens anxious to learn the nature of the speeches made by the several Senators. Every hall and corridor, every stairway and lobby, and every yard of tenable space from the rotunda to the farthest corner of the Senate wing was occupied. The hungry crowd was “voracious for news.” Occasionally a Senator came out to get his lunch at the adjoining refreshment saloon. He was at once surrounded by his friends, and scrap by scrap the news was wrenched from his reluctant lips.

SCENE IN NEWSPAPER ROW.

The offices of the correspondents of the various newspapers throughout the country are located under the Ebbitt House, in Fourteenth Street, and to this focus of news the crowd tended on the night after the vote had been taken. The sidewalk on Newspaper Row was blockaded during the whole evening by anxious searchers after news, and the offices of the New York papers, and that of the Cincinnati Gazette agent were crowded until midnight. But as it is the duty of the correspondent to collect news of the many and dispense it only to his editor, the crowd became the dispenser of rumors rather than the recipient of facts.

Edmund G. Ross, one of the senators who voted “Not Guilty” wrote about the May 16th decision. From History of the Impeachment of Andrew Johnson, President of The United States By The House Of Representatives and His Trial by The Senate for High Crimes and Misdemeanors in Office (published in 1868 at Project Gutenberg):

… Under these conditions it was but natural that during the trial, and especially as the close approached, the streets of Washington and the lobbies of the Capitol were thronged from day to day with interested spectators from every section of the Union, or that Senators were beleaguered day and night, by interested constituents, for some word of encouragement that a change was about to come of that day’s proceeding, and with threats of popular vengeance upon the failure of any Republican Senator to second that demand.

In view of this intensity of public interest it was as a matter of course that the coming of the day when the great controversy was expected to be brought to a close by the deposition of Mr. Johnson and the seating of a new incumbent in the Presidential chair, brought to the Capitol an additional throng which long before the hour for the assembling of the Senate filled all the available space in the vast building, to witness the culmination of the great political trial of the age.

Upon the closing of the hearing—even prior thereto, and again during the few days of recess that followed, the Senate had been carefully polled, and the prospective vote of every member from whom it was possible to procure a committal, ascertained and registered in many a private memoranda. There were fifty-four members—all present. According to these memoranda, the vote would stand eighteen for acquittal, thirty-five for conviction—one less than the number required by the Constitution to convict. What that one vote would be, and could it be had, were anxious queries, of one to another, especially among those who had set on foot the impeachment enterprise and staked their future control of the government upon its success. Given for conviction and upon sufficient proofs, the President MUST step down and out of his place, the highest and most honorable and honoring in dignity and sacredness of trust in the constitution of human government, a disgraced man and a political pariah. If so cast upon insufficient proofs or from partisan considerations, the office of President of the United States would be degraded—cease to be a coordinate branch of the Government, and ever after subordinated to the legislative will. It would have practically revolutionized our splendid political fabric into a partisan Congressional autocracy. Apolitical tragedy was imminent.

On the other hand, that vote properly given for acquittal, would at once free the Presidential office from imputed dishonor and strengthen our triple organization and distribution of powers and responsibilities. It would preserve the even tenor and courses of administration, and effectively impress upon the world a conviction of the strength and grandeur of Republican institutions in the hands of a free and enlightened people.

The occasion was sublimely and intensely dramatic. The President of the United States was on trial. The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court was presiding over the deliberations of the Senate sitting for the trial of the great cause. The board of management conducting the prosecution brought by the House of Representatives was a body of able and illustrious politicians and statesmen. The President’s counsel, comprising jurists among the most eminent of the country, had summed up for the defense and were awaiting final judgment. The Senate, transformed for the occasion into an extraordinary judicial tribunal, the highest known to our laws, the Senators at once judges and jurors with power to enforce testimony and sworn to hear all the facts bearing upon the case, was about to pronounce that judgment.

The organization of the court had been severely Democratic. There were none of the usual accompaniments of royalty or exclusivism considered essential under aristocratic forms to impress the people with the dignity and gravity of a great occasion. None of these were necessary, for every spectator was an intensely interested witness to the proceeding, who must bear each for himself, the public consequences of the verdict, whatever they might be, equally with every member of the court.

The venerable Chief Justice, who had so ably and impartially presided through the many tedious weeks of the trial now about to close, was in his place and called the Senate to order.

The impressive dignity of the occasion was such that there was little need of the admonition of the Chief Justice to abstention from conversation on the part of the audience during the proceeding. No one there present, whether friend or opponent of the President, could have failed to be impressed with the tremendous consequences of the possible result of the prosecution about to be reached. The balances were apparently at a poise. It was plain that a single vote would be sufficient to turn the scales either way—to evict the President from his great office to go the balance of his life’s journey with the brand of infamy upon his brow, or be relieved at once from the obloquy the inquisitors had sought to put upon him—and more than all else, to keep the honorable roll of American Presidents unsmirched before the world, despite the action of the House.

The first vote was on the Eleventh and last Article of the Impeachment. Senators voted in alphabetical order, and each arose and stood at his desk as his name was called by the Chief Clerk. To each the Chief Justice propounded the solemn interrogatory—”Mr. Senator—, how say you—is the respondent, Andrew Johnson, President of the United States, guilty or not guilty of a high misdemeanor as charged in this Article?”

Mr. Fessenden, of Maine, was the first of Republican Senators to vote “Not Guilty.” He had long been a safe and trusted leader in the Senate, and had the unquestioning confidence of his partisan colleagues, while his long experience in public life, and his great ability as a legislator, and more especially his exalted personal character, had won for him the admiration of all his associates regardless of political affiliations. Being the first of the dissenting Republicans to vote, the influence of his action was feared by the impeachers, and most strenuous efforts had been made to induce him to retract the position he had taken to vote against conviction. But being moved on this occasion, as he had always been on others, to act upon his own judgment and conviction, though foreseeing that this vote would probably end a long career of conspicuous public usefulness, there was no sign of hesitancy or weakness as he pronounced his verdict.

Mr. Fowler, of Tennessee, was the next Republican to vote “Not Guilty.” He had entered the Senate but two years before, and was therefore one of the youngest Senators, with the promise of a life of political usefulness before him. Though from the same State as the President, they were at political variance, and there was but little in common between them in other respects. A radical partisan in all measures where radical action seemed to be called for, he was for the time being sitting in a judicial capacity and under an oath to do justice to the accused according to the law and the evidence. As in his judgment the evidence did not sustain the charge against the President such was his verdict.

Mr. Grimes, of Iowa, was the third anti-impeaching Republican to vote. He had for many years been a conspicuous and deservedly influential member of the Senate. For some days prior to the taking of the vote he had been stricken with what afterwards proved a fatal illness. The scene presented as he rose to his feet supported on the arms of his colleagues, was grandly heroic, and one never before witnessed in a legislative chamber. Though realizing the danger he thus incurred, and conscious of the political doom that would follow his vote, and having little sympathy with the policies pursued by the President, he had permitted himself to be borne to the Senate chamber that he might contribute to save his country from what he deemed the stain of a partisan and unsustained impeachment of its Chief Magistrate. Men often perform, in the excitement and glamour of battle, great deeds of valor and self sacrifice that live after them and link their names with the honorable history of great events, but to deliberately face at once inevitable political as well as physical death in the council hall, and in the absence of charging squadrons; and shot and shell, and of the glamor of military heroism, is to illustrate the grandest phase of human courage and devotion to convictions. That was the part performed by Mr. Grimes on that occasion. His vote of “Not Guilty” was the last, the bravest, the grandest, and the most patriotic public act of his life.

Mr. Henderson of Missouri, was the fourth Republican Senator to vote against the impeachment. A gentleman of rare industry and ability, and a careful, conscientious legislator, he had been identified with the legislation of the time and had reached a position of deserved prominence and influence. But he was learned in the law, and regardful of his position as a just and discriminating judge. Though then a young man with a brilliant future before him, he had sworn to do justice to Andrew Johnson “according to the Constitution and law,” and his verdict of “Not Guilty” was given with the same deliberate emphasis that characterized all his utterances on the floor of the Senate.

Mr. Ross, of Kansas, was the fifth Republican Senator to vote “Not Guilty.” Representing an intensely Radical constituency—entering the Senate but a few months after the close of a three years enlistment in the Union Army and not unnaturally imbued with the extreme partisan views and prejudices against Mr. Johnson then prevailing—his predilections were sharply against the President, and his vote was counted upon accordingly. But he had sworn to judge the defendant not by his political or personal prejudices, but by the facts elicited in the investigation. In his judgment those facts did not sustain the charge.

Mr. Trumbull, of Illinois, was the sixth Republican Senator to vote against the Impeachment. He had been many years in the Senate. In all ways a safe legislator and counsellor, he had attained a position of conspicuous usefulness. But he did not belong to the legislative autocracy which then assumed to rule the two Houses of Congress. To him the Impeachment was a question of proof of charges brought, and not of party politics or policies. He was one of the great lawyers of the body, and believed that law was the essence of justice and not an engine of wrong, or an instrumentality for the satisfaction of partisan vengeance. He had no especial friendship for Mr. Johnson, but to him the differences between the President and Congress did not comprise an impeachable offense. A profound lawyer and clear headed politician and statesman, his known opposition naturally tended to strengthen his colleagues in that behalf.

Mr. Van Winkle, of West Virginia, was the seventh and last Republican Senator to vote against the Impeachment. Methodical and deliberate, he was not hasty in reaching the conclusion he did, but after giving the subject and the testimony most careful and thorough investigation, he was forced to the conclusion that the accusation brought by the House of Representatives had not been sustained, and had the courage of an American Senator to vote according to his conclusions. …

In Profiles in Courage, published in 1955, John F. Kennedy and/or Ted Sorenson also mentioned the bravery of each of the seven senators, but their focus was on Edmund G. Ross:

The night before the Senate was to take its first vote for the conviction or acquittal of Johnson, Ross received this telegram from home:

Kansas has heard the evidence and demands the conviction of the President.

(signed) D.R. ANTHONY AND 1,000 OTHERS

And on that fateful morning of May 16 Ross replied:

To D.R. Anthony and 1,000 Others: I do not recognize your right to demand that I vote either for or against conviction. I have taken an oath to do impartial according to the Constitution and laws, and trust that I shall have the courage to vote according to the dictates of my judgment and for the highest good of my country.

[signed] – E.G. ROSS[1]

The Wikipedia article above about JFK’s book mentions that there was some evidence that Senator Ross was bribed for his vote. Hans L. Trefousse wrote that there was some bargaining over the vote:

Senator Edmund G. Ross of Kansas also received assurances from the president. Anxious to see congressional reconstruction put into effect, on May 4 the senator approached the White House through intermediaries and asked that Johnson transmit the radical constitutions of South Carolina and Arkansas without delay. The gesture would have a salutary effect, and he and others could vote for acquittal. Johnson promptly complied. …[2]

There were still ten other Articles of Impeachment, but after the May 16th vote, the Senate adjourned for ten days.

All the images from Harper’s Weekly can be found at the Internet Archive