Not exactly lively, not exactly dry

better hurry

The 18th amendment to the United States Constitution, prohibiting the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all the territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes,” went into effect nationwide on January 17, 1920. That might have been bad enough, but Prohibition reportedly even affected the prior New Year’s Eve in New York City. The big night had been a subdued affair according to the January 1, 1920 issue of the The New-York Times, which headlined a New Year’s Eve “Gay in Hotels, Quiet on Streets,” “Abundance of Liquor in Dining Rooms, Brought in Packages by the Guests,” … “Revenue Agents Vigilant,” “Mingled in Restaurant Crowds in Evening Dress, Some Accompanied by Their Wives”:

A sober city gave tacit notice to the world that prohibition and the attendant fear of beverages tainted with wood alcohol had caused it to abandon forever its time-honored custom of greeting the New Year by turning its Broadway and Times Square into a Mardi Gras, where good-natured throngs took part in revels and bantering until the cold morning mists drove them home.

New Year’s Eve as an institution and as a great expression of a community psychology, a psychology that caused thousands in other years to gather into a great Broadway maelstrom, has passed into the city’s history. Hard hit by the war and overshadowed by the great Armistice Night celebration, the riotous New Year’s Eve of a year ago failed to return to its haunts last night under the most favorable weather conditions. Cause: Prohibition!

Little Gayety in Streets.

could you please direct me to the Mardi Gras?

Only in the hotels and the restaurants along Broadway was there any hint last night of the old prewar New Year’s Eve, with its ear-rending, noise-making machines, its feather ticklers, its confetti, its trumpets, its immovable crowds, and its good cheer. There the last precious drops of good old bonded stuff were used up by diners who sought to bring back the oldtime New Year’s Eve and to make themselves believe that they at least for this one year could outwit prohibition.

Although an insidious rumor had bed spread far and wide that some of the hotels would open their hearts and their wine cellars at the stroke of midnight and carry forth casks of the good cheer which they were forbidden by law to sell, no such theatrical munificence was carried out, save, to a limited extent, in the hotels of the du Pont-Boomer group. Hoping against hope, hundreds of patrons placed themselves in receptive positions in all hotels, but at midnight the managers came around and shook hands. Nothing else! …

The same front page described a raid on a shop in Brooklyn that manufactured poison wood alcohol that “caused many deaths in Hartford, Chicopee, and other places in New England …”

on the wagon,

Uncle Sam’s wagon

bathtub gin?

dry cabaret

August 1919???

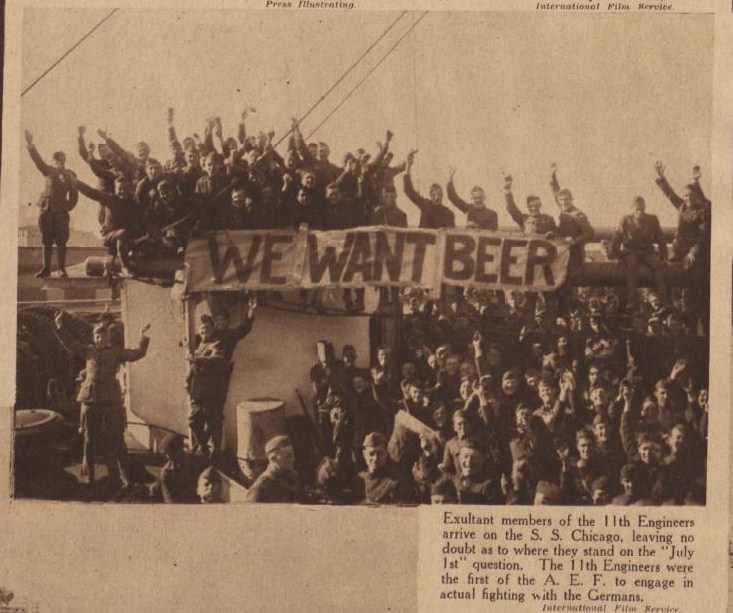

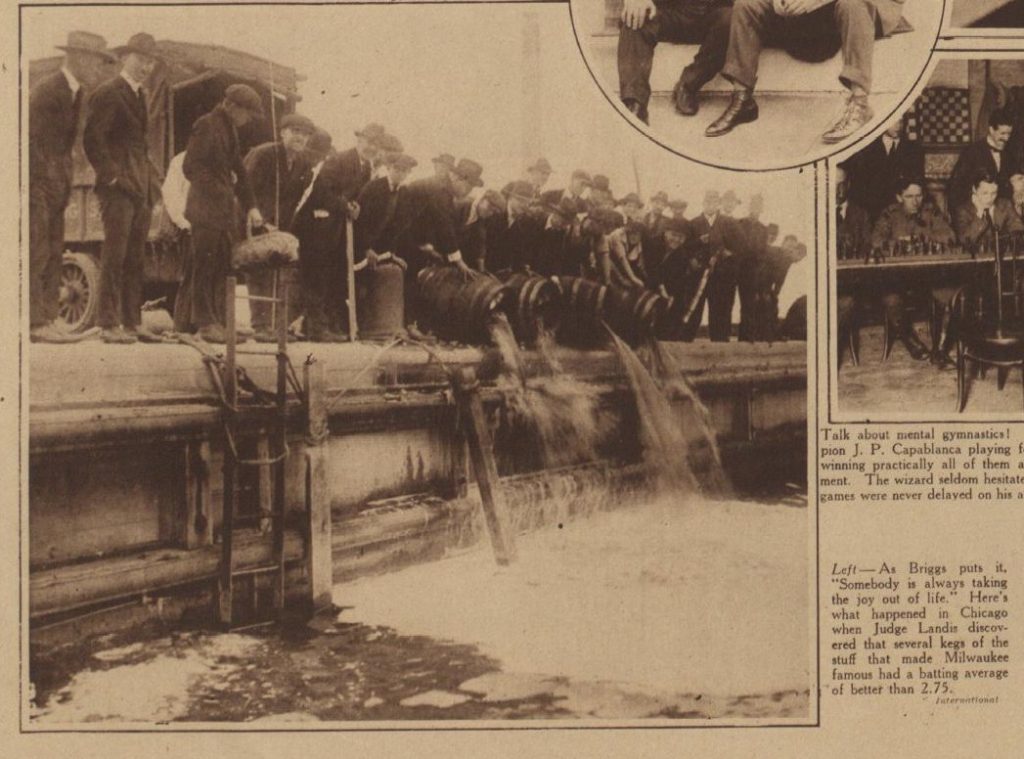

__________________________________

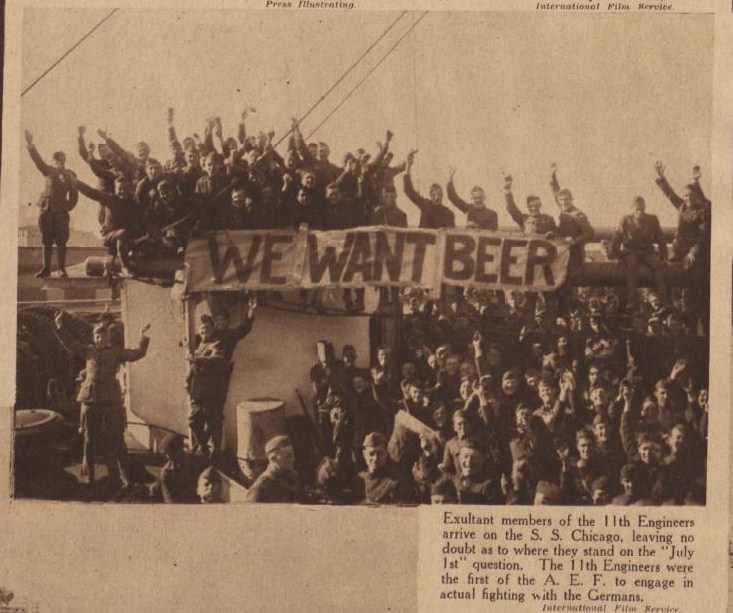

The Volstead Act, passed in October 1919, specified how the eighteenth amendment was to be carried out, but I still didn’t understand how enforcement of prohibition seemed to begin before January 17, 1920 until I found a picture at the Library of Congress and then found information about the Wartime Prohibition Act at chronozoom: the act “banned the sale of alcoholic beverages having an alcohol content of greater than 2.75 percent. (This act, which was intended to save grain for the war effort, was passed after the armistice ending World War I was signed on November 11, 1918.) The Wartime Prohibition Act took effect June 30, 1919, with July 1, 1919, becoming known as the “Thirsty-First”.”

last call for (full-strength) alcohol

An American history textbook viewed Prohibition as a victory for rural America against the cities. The temperance movement had been a strong force since Andrew Jackson’s administration and during the Progressive Era many reformers wanted to ban alcohol entirely. “(P)rohibition was a typical progressive reform, moralistic, backed by the middle class, aimed at frustration ‘the interests’ – in this case, the distillers.” World War I was a boon to the movement – the Food and Fuel Control Act also controlled alcohol because it “banned the production of “distilled spirits” from any produce that was used for food.” Apparently it reduced the permissible alcohol content in legal beer. Prohibition had good and bad results. The amendment did reduce average alcohol consumption and resulted in fewer alcohol-related deaths. Since beer and wine were also banned, many citizens opted to break the law. Smuggling increased and saloons were replaced by speakeasies. The legal production of wine for religious services increased “800,000 gallons during the first two years of prohibition.” Pharmacists could legally prescribe alcohol for medicinal purposes. Overall prohibition led to a lot of societal hypocrisy.[]

British author G.K Chesterton had quite a bit to say about Prohibition in his 1922 What I Saw in America (at Project Gutenberg). Here are a few excerpts:

I went to America with some notion of not discussing Prohibition. But I soon found that well-to-do Americans were only too delighted to discuss it over the nuts and wine. They were even willing, if necessary, to dispense with the nuts. I am far from sneering at this; having a general philosophy which need not here be expounded, but which may be symbolised by saying that monkeys can enjoy nuts but only men can enjoy wine. But if I am to deal with Prohibition, there is no doubt of the first thing to be said about it. The first thing to be said about it is that it does not exist. It is to some extent enforced among the poor; at any rate it was intended to be enforced among the poor; though even among them I fancy it is much evaded. It is certainly not enforced among the rich; and I doubt whether it was intended to be. I suspect that this has always happened whenever this negative notion has taken hold of some particular province or tribe. Prohibition never prohibits. It never has in history; not even in Moslem history; and it never will. Mahomet at least had the argument of a climate and not the interest of a class. But if a test is needed, consider what part of Moslem culture has passed permanently into our own modern culture. You will find the one Moslem poem that has really pierced is a Moslem poem in praise of wine. The crown of all the victories of the Crescent is that nobody reads the Koran and everybody reads the Rubaiyat.

Most of us remember with satisfaction an old picture in Punch, representing a festive old gentleman in a state of collapse on the pavement, and a philanthropic old lady anxiously calling the attention of a cabman to the calamity. The old lady says, ‘I’m sure this poor gentleman is ill,’ and the cabman replies with fervour, ‘Ill! I wish I ‘ad ‘alf ‘is complaint.’ …

Now Prohibition, whether as a proposal in England or a pretence in America, simply means that the man who has drunk less shall have no drink, and the man who has drunk more shall have all the drink. It means that the old gentleman shall be carried home in the cab drunker than ever; but that, in order to make it quite safe for him to drink to excess, the man who drives him shall be forbidden to drink even in moderation. That is what it means; that is all it means; that is all it ever will mean. It tends to that in Moslem countries; where the luxurious and advanced drink champagne, while the poor and fanatical drink water. It means that in modern America; where the wealthy are all at this moment sipping their cocktails, and discussing how much harder labourers can be made to work if only they can be kept from festivity. This is what it means and all it means; and men are divided about it according to whether they believe in a certain transcendental concept called ‘justice,’ expressed in a more mystical paradox as the equality of men. So long as you do not believe in justice, and so long as you are rich and really confident of remaining so, you can have Prohibition and be as drunk as you choose. …

sine qua non

class consciousness

verboten

Now my primary objection to Prohibition is not based on any arguments against it, but on the one argument for it. I need nothing more for its condemnation than the only thing that is said in its defence. It is said by capitalists all over America; and it is very clearly and correctly reported by Mr. Campbell himself. The argument is that employees work harder, and therefore employers get richer. That this idea should be taken calmly, by itself, as the test of a problem of liberty, is in itself a final testimony to the presence of slavery. It shows that people have completely forgotten that there is any other test except the servile test. Employers are willing that workmen should have exercise, as it may help them to do more work. They are even willing that workmen should have leisure; for the more intelligent capitalists can see that this also really means that they can do more work. But they are not in any way willing that workmen should have fun; for fun only increases the happiness and not the utility of the worker. Fun is freedom; and in that sense is an end in itself. It concerns the man not as a worker but as a citizen, or even as a soul; and the soul in that sense is an end in itself. That a man shall have a reasonable amount of comedy and poetry and even fantasy in his life is part of his spiritual health, which is for the service of God; and not merely for his mechanical health, which is now bound to the service of man. The very test adopted has all the servile implication; the test of what we can get out of him, instead of the test of what he can get out of life. …

Nobody in his five wits will deny that Jeffersonian democracy wished to give the law a general control in more public things, but the citizens a more general liberty in private things. Wherever we draw the line, liberty can only be personal liberty; and the most personal liberties must at least be the last liberties we lose. But to-day they are the first liberties we lose. It is not a question of drawing the line in the right place, but of beginning at the wrong end. What are the rights of man, if they do not include the normal right to regulate his own health, in relation to the normal risks of diet and daily life? Nobody can pretend that beer is a poison as prussic acid is a poison; that all the millions of civilised men who drank it all fell down dead when they had touched it. Its use and abuse is obviously a matter of judgment; and there can be no personal liberty, if it is not a matter ofprivate judgment. It is not in the least a question of drawing the line between liberty and licence. If this is licence, there is no such thing as liberty. It is plainly impossible to find any right more individual or intimate. To say that a man has a right to a vote, but not a right to a voice about the choice of his dinner, is like saying that he has a right to his hat but not a right to his head.

Prohibition, therefore, plainly violates the rights of man, if there are any rights of man. What its supporters really mean is that there are none.

social compact?

Sometimes I get so blue because of all the gray areas in life. Alcohol is a good example. One of my memories of Gettysburg when I was a little kid [] was visiting the Cyclorama – I heard an agonizing scream as the spotlight highlighted a near-battlefield amputation; I hope that soldier, regardless of uniform, could have had some whiskey to ease the pain a little bit. On the other hand, I’m quite certain that drinking can lead to something approaching the exact opposite of personal liberty, with an increasing likelihood of collateral damage

Apparently doctors even in the early twentieth century relied on alcohol as a medicine. The front page of The New-York Times on January 22, 1919 headlined an increase in city influenza cases of 462 in one day and a concern that because of prohibition it would be difficult to obtain enough whiskey to treat the flu and pneumonia. (the other concern was a shortage of nurses, especially for home care). The Health Commissioner planned on asking the federal government to set up liquor stations where medical professional could obtain the stuff to treat patients. Druggists were worried that they could get in trouble if they filled too many prescriptions for medicinal alcohol now that the liquid was banned nationwide.

I was surprised to read that G.K. Chesterton didn’t think Muslims read the Koran, although that was about one hundred years ago.

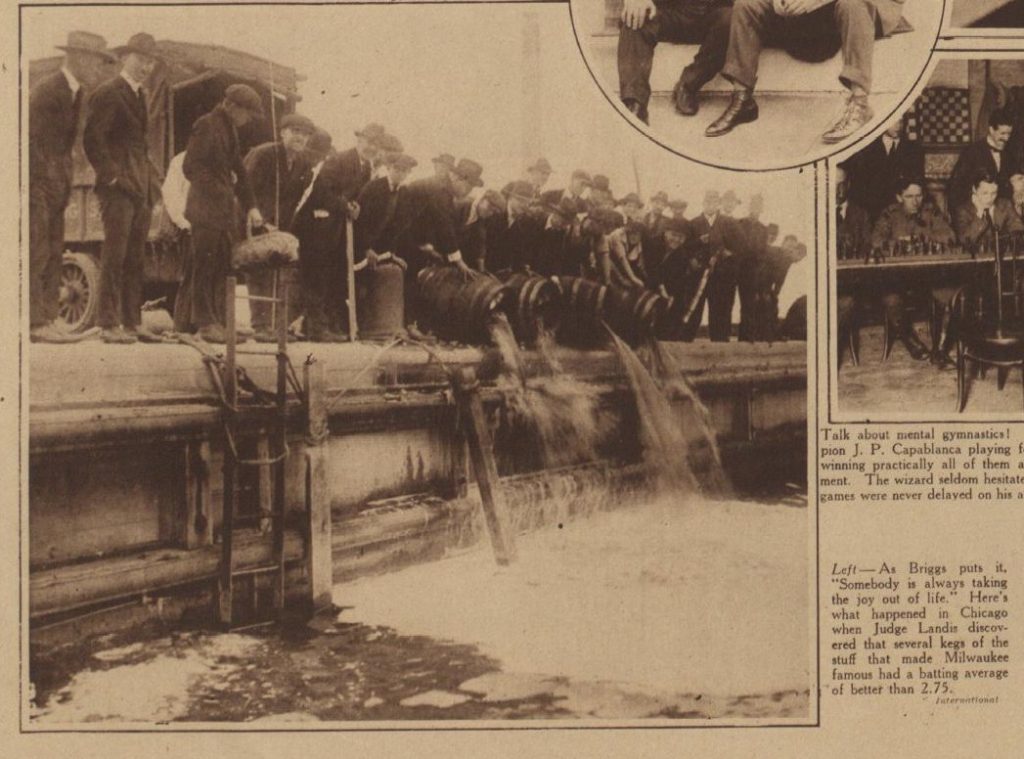

Kenesaw Mountain Landis served as a judge on the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois from 1905-1922 and as Baseball Commissioner from 1920 until his death in 1944.

You can read a blog about Prohibition at the Library of Congress.

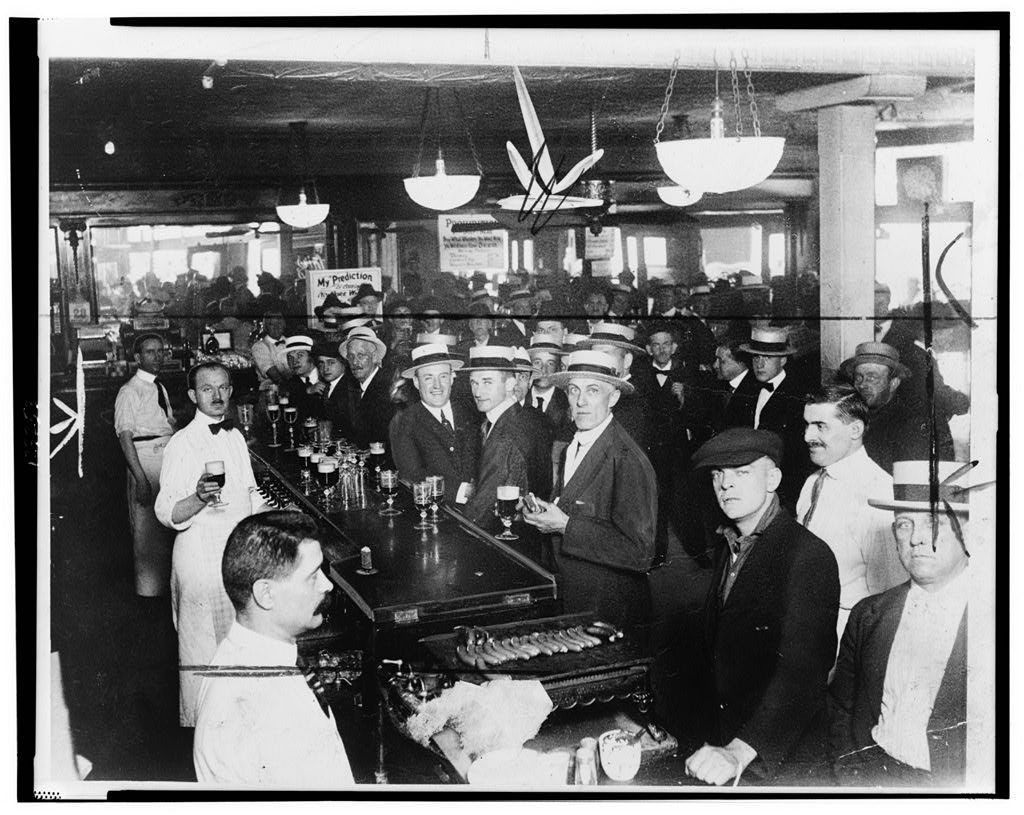

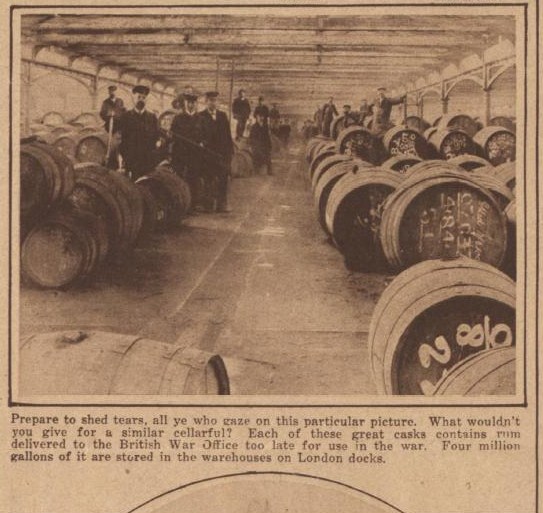

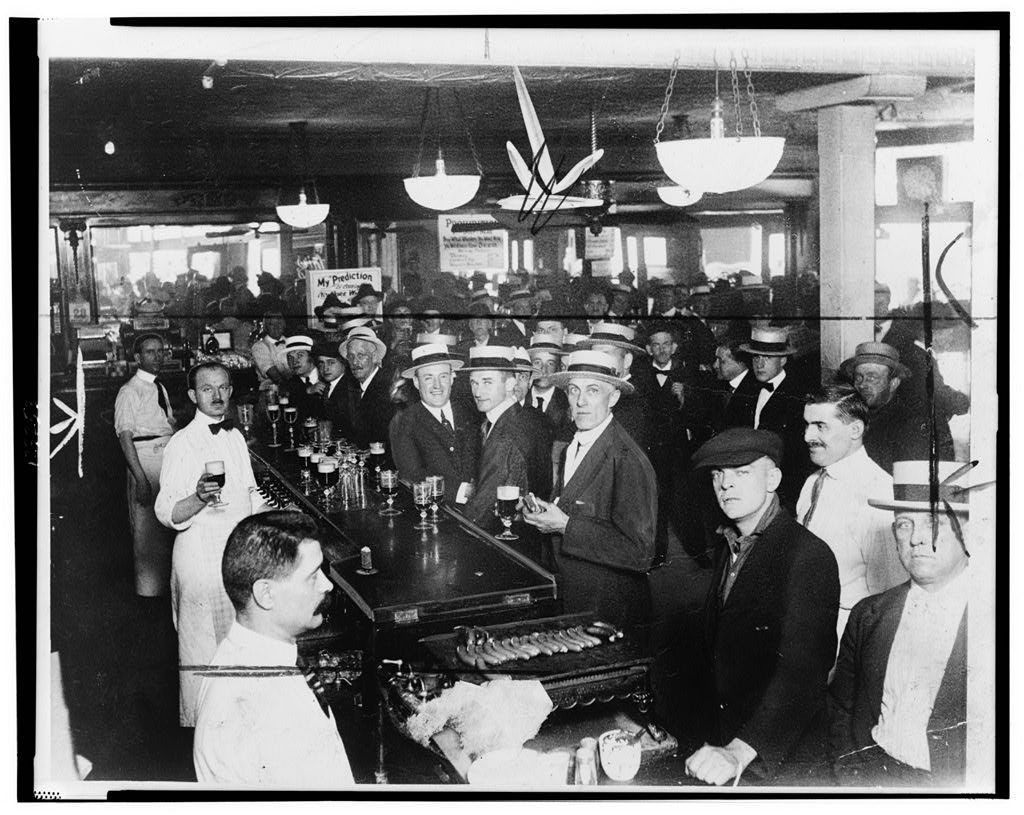

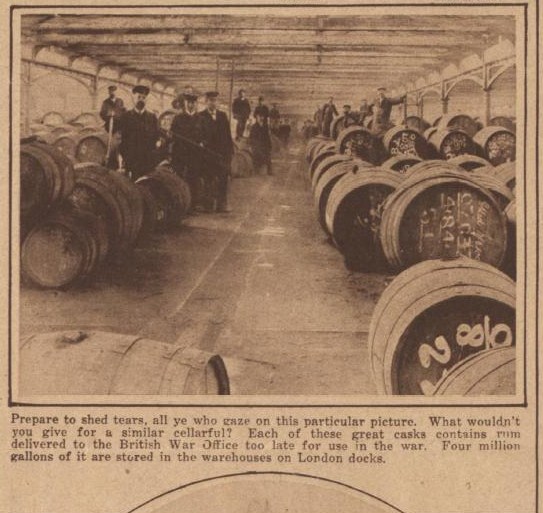

Also from the Library of Congress: the photo of the returning 11th Engineers from the May 4, 1919 issue of the New York Tribune – a couple months before the Wartime Prohibition Act took effect; also from the Trib in 1919 – August 3rd, October 19th, November 9th, December 7th, December 28th; a quiet Times Square between 1900 and 1915; “Interior of a crowded bar moments before midnight, June 30, 1919, when wartime prohibition went into effect New York City;” “No Beer-No Work sheet music from 1919; Personal Liberty sheet music also from 1919; Bottles and barrel of confiscated whiskey/a>

cellar dwellers?

down with drink

killjoys