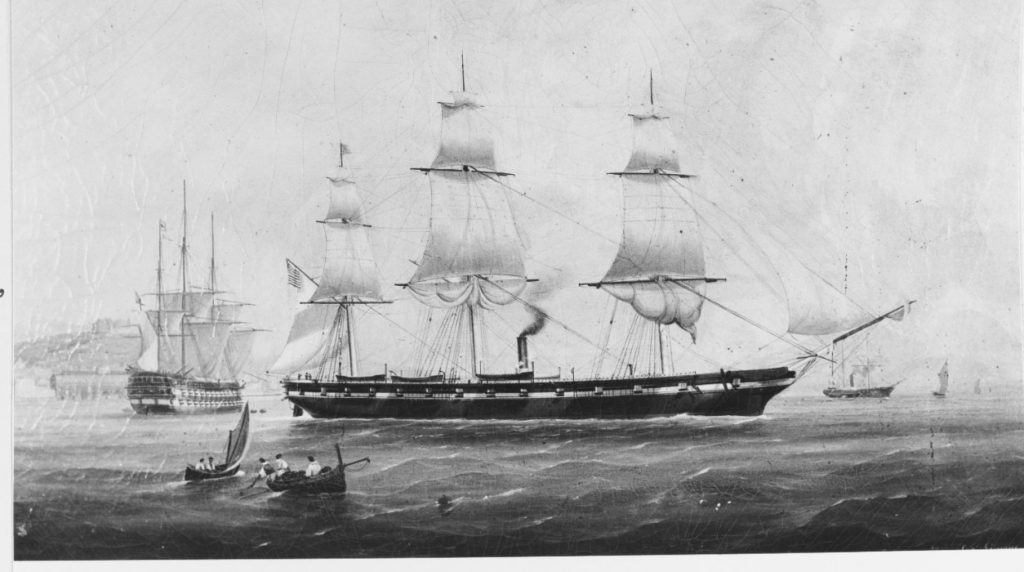

When the recently-launched (January) USS Richmond departed for the Mediterranean on October 13, 1860, its namesake was the capital of one of the United States, albeit one of the original thirteen – Virginia, the Old Dominion. When the ship returned to New York on July 3, 1861, Richmond was still Virginia’s state capital, but it had taken on another role – the national capital of the breakaway Confederate States of America. According to the September 7, 1919 issue of the New York Tribune, the Richmond spent the American Civil War helping force the rebels back into the Union.

I haven’t seen any evidence that the Richmond ever served as David Farragut’s flagship, but it was actively engaged throughout the Civil War. According to the U.S. Navy this second iteration of the USS Richmond began its war career in late July 1861 by sailing for Jamaica, looking for “the elusive Confederate raider Sumter commanded by Raphael Semmes”. The Richmond couldn’t find the Sumter either, so then joined the Gulf Blockading Squadron and patrolled the mouth of the Mississippi. During the Battle of the Head of Passes on October 12, 1861 the Confederate ram Manassas rammed but did not disable the Richmond. Later in 1861 the ship’s crew suffered some casualties and the ship was furthered damaged from rebel fire during the bombardment of Pensacola Navy Yard.

__________________

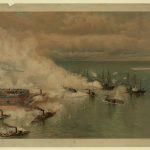

After repairs in New York the Richmond joined the West Gulf Blockading Squadron under Flag Officer David Farragut and was actively involved in the Union operations that captured New Orleans. Farragut’s fleet continued to focus on the Mississippi River until the Union capture of Vicksburg and Port Hudson in July 1863. During that period one of the war’s “fiercest engagements” occurred when the fleet, heading upriver, attempted to pass rebel fortifications at Port Hudson in March 1863. “Richmond, lashed alongside Genesee, found she could make no headway against the strong current as she came under fire from the shore batteries. Her executive officer, Comdr. Andrew B. Cummings, was mortally wounded. Richmond was struck soon afterward by a 42-pounder shell which ruptured her steam lines, filling the engine room and berth deck with live steam. As Genessee [sic; Genesee] was unable to tow Richmond against the current, the two ships reversed course, passing again through heavy shore fire.”

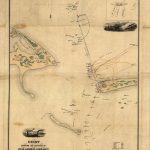

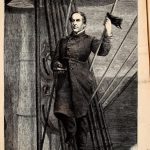

The Richmond was again repaired in New York and then rejoined the blockading squadron by November 1863. It participated in Admiral Farragut’s assault on Mobile Bay on August 5, 1864. This time the Richmond was lashed to the Port Royal as it proceeded across the bar with the rest of the Union fleet and ran the gauntlet between two Confederate forts and through a channel planted with torpedoes (mines). After the monitor Tecumseh struck a torpedo and quickly sunk, the other Union ships hesitated. At this point, Admiral Farragut, lashed to the mast of his flagship Hartford, ordered the Union ships to sail full-speed through the minefield. Once in the bay, the Union ships defeated the Confederate fleet that same morning. “Richmond suffered no casualties in the action and only slight damage.”

________________

After the war Richmond got a new set of engines, was recommissioned in 1869, and returned to the Mediterranean. 150 years ago this year the ship “was stationed at Villefranche and Marseille [sic; Marseilles] to protect U.S. citizens potentially endangered by the Franco-Prussian War”. Later on Richmond did serve as a flagship: first with the South Pacific Station (1874-1877); then with the Asiatic Fleet (1879-83) – “For 4 years Richmond cruised among the principal ports of China, Japan, and the Philippines;” from 1889 to 1890 Richmond was the flagship of the South Atlantic Station. For the rest of its career it was used as a training ship, receiving ship, and finally at Norfolk as an “auxiliary to the receiving ship Franklin until after the end of World War I”.

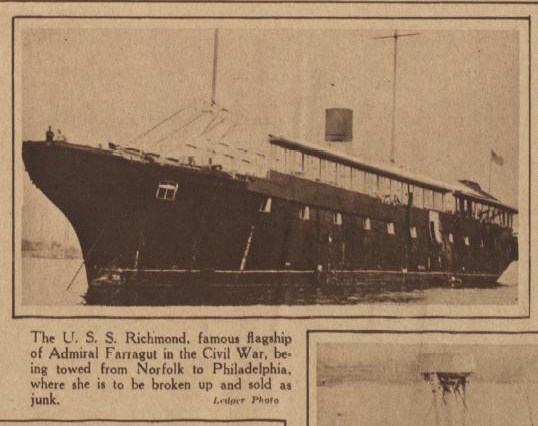

“Richmond was struck from the Navy list on 31 June 1919 and sold to Joseph Hyman & Sons, Philadelphia, Pa., on 23 July. She was delivered to that firm on 6 August for breaking up.”

According to other documentation at the U.S. Navy website, the Richmond was burned for scrap in Eastport Maine. Even though the ship had apparently been sold to a private company, Assistant Secretary of the Navy F.D. Roosevelt “witnessed this event”:

Oh, to be an auxiliary to a receiving ship … A couple months ago I read a seemingly pertinent essay. [1] Arthur Brooks contrasted the careers of two famous geniuses. Both Charles Darwin and Johann Sebastian Bach achieved enormous success and notoriety when they were young, and both were unable to emulate their achievements later on in life; but Mr. Darwin had more trouble adapting to changed circumstances. His research abilities plateaued during his 50s, and he became depressed. Mr. Bach was a gifted baroque composer and musician, but then classical music replaced baroque in popularity. Unlike Darwin, J.S. Bach didn’t become embittered; instead he redesigned his life and spent his last years writing a baroque instruction manual. Mr. Brooks advises those over 50 to avoid the despondency and inactivity of Charles Darwin and be like Bach, the beloved, fulfilled, respected Bach.

Or Ulysses S. Grant? I recently noticed Grant’s famous visage in an article about retiring early. [2] Back when MONEY published a paper magazine, it asked experts for books that they’d suggest for those seeking “financial independence and early retirement.” Ron Chernow’s Grant surprisingly made the list even though it isn’t “about retiring early, per se.” John Challenger, a CEO of an outplacement firm, sees Grant’s life as an example of “how people were able to pivot and adapt to their situations to make significant advances in their careers.” The general and president repeatedly reinvented himself. He was famously working hard at the very end of his life, this time as a memoirist, and not because he had the financial independence to do a little writing in a larger amount of spare time – he was trying to put his family finances back in shape after a ponzi scheme left his family destitute. And toward the end he was trying to finish the second volume of his memoirs before his imminent death.

It might be a stretch to say that the Richmond reinvented itself, but the ship did seem to take on several different roles throughout its career, and, perhaps a bit like Bach, it was able to stay useful as society’s/technology’s cutting edge left it behind. I’ve never been a genius or a flagship sailing the Seven Seas; it seems most of my career has been trying to work out a career, but my body and my brain are definitely slowing down and I’m more and more out of step with societal changes. If I make it to retirement, I’m hoping for something of the usefulness of an auxiliary receiving ship, probably with time for a few more naps. [March 23, 2020 – that might be what they call semi-retirement, although there are many ways to be useful without paid work].

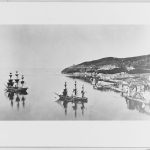

“Stripped for action, at Pensacola, Florida, on 3 August 1864, just prior to the Battle of Mobile Bay ( Richmond on the left with the Lackawanna)