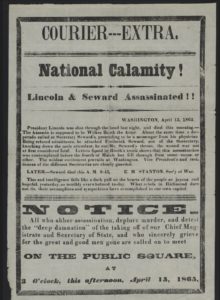

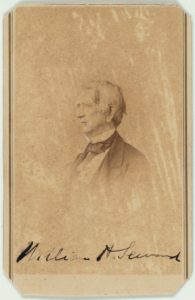

On October 10, 1872 former U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward died at his home in Auburn, New York. People in the Midwest could read all about it the next day. From the October 11, 1872 issue of The Chicago Daily Tribune:

WILLIAM H. SEMARD. [SIC]

Death of the Venerable Statesman at

His Home in Auburn, N. Y.

Death of Ex-Secretary Seward.

AUBURN, N.Y., Oct. 10.-Hon. William H. Seward died at his residence in this city this afternoon at fifteen minutes past 3 o’clock.

ALBANY, N. Y., Oct. 10.—The sudden announcement of the death of Wm. H. Seward caused a profound sensation here. It was unexpected and has produced wide-spread regret.

WASHINGTON, Oct. 30.—The announcement of the death of Mr. Seward is received with regret in all quarters. The State Department building will, as a mark of respect to his memory, be draped with mourning.

AUBURN, N. Y., Oct. 10.—Mr. Seward having taken cold and been somewhat unwell for a day or two, was, on the evening of Saturday, the 5th, seized with a severe chill, and his physician was summoned to him. He had been during the summer in his ordinary good health, suffering only from inconvenience of muscular palsy of his arms, and had been engaged in preparing for the press his account of his recent journey around the world. The chill was that of ordinary tertian ague, accompanied by a harassing catarrhal cough, It was followed by fever and delirium, which lasted till late in the night. On Sunday he was up in the afternoon took his dinner, and passed a comfortable night. On Monday, with the exception of the cough and catarrh, he was comfortable, and dictated as usual to his assistants. On the completion of his book, he played whist Monday evening, but at 10 p.m. a slight chill occurred, followed by delirium and fever, with aggravated catarrhal disturbance of the chest, which lasted nearly all night, his physician seeing him, on this account, after midnight. On Tuesday morning, after some sleep, he was again better, and drove out in the afternoon, but fever, delirium, and restlessness returned with the cough on Tuesday night. On Wednesday he drove oat for two hours, and dictated to his amannenuis as usual, though harassed all day with cough and catarrhal effusions in the chest. On Wednesday evening cough abated for a while, and there seemed a promise of a good night, but the fever, restlessness, and cough returned at bed-time. He was nearly sleepless until 5 o’clock in the morning. At 4 a.m., to relieve the tedium of lying sleepless, he had his son William read the New York Times to him of Wednesday evening. He slept after 5 pretty well till 11 a. m. to-day, though his fever kept up without any real remission. At half-pest 1 he was seized with great difficulty in breathing, caused by a sudden catarrhal effusion into the lungs, commencing with the right lung, and soon involving the left also, which occasioned his death in about two hours. He entertained no apprehension but he should recover from the attack of catarrhal ague, till last night and this morning. While at his age and with the condition of muscular palsy, from which he has suffered so long, the fact that the fever was increasing upon him, together with the catarrhal disturbance, led his physician to apprehend a fatal result. In the course of a week or more, yet no immediate fear was felt, and his dissolution was sudden and unexpected.

Mr. Seward’s intellectual faculties were clear and vigorous to the last, save when disturbed by paroxysms of fever. Just after the effusion from the lungs to-day, and thinking it would relieve his breathing, he was, at his own desire, placed on a lounge and bolstered up and removed from his adjoining bed-room into the study, where, in the midst of his books, and his literary and other papers, and surrounded by his relatives and a few friends, and all his devoted dependents, he breathed his last. For the last hour of his life, as the powers of nature was giving way, his condition became easy, and he spent the time in affectionate leave-taking of relations and dependents, and finally sank quietly to his last rest as if going to sleep.

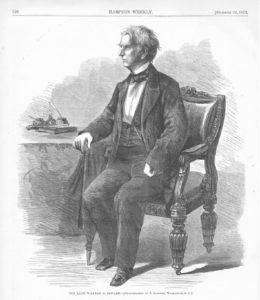

Harper’s Weekly provided two takes on Mr. Seward’s career in its October 26, 1872 issue.

Page 828:

WILLIAM HENRY SEWARD.

THE death of this venerable statesman, who passed away a few days since at his quiet country home, was an event for which the public had been for some time prepared, yet the announcement of his decease came at last like a sudden shock. Mr. SEWARD had lived so long in the public eye, his history was so interwoven with the great events of the last twenty years, that it seems hardly possible to realize the fact that he is gone from among us. He was not a very old man in years: but for physical infirmities, increased by long and arduous public service, and by the assassin’s attack which so nearly deprived us of his great services when we could least spare them, he might have lived many years in the honorable retirement which crowned a public career of nearly half a century, passed in the midst of great events, and devoted to the highest and truest interests of his country.

It were vain to attempt, in the meagre space of a single article, to give even an outline sketch of his public life. Nor is it necessary. Mr. SEWARD lived before the eyes of all his countrymen. From the opening of his career until its close he took a prominent part in all the great movements of the day. An early disciple of JEFFERSON and JOHN QUINCY ADAMS, always faithful to the fundamental American principle of equal rights before the law, his public life was conspicuous and illustrious. His trust in popular institutions, in their capacity to right all wrongs, to correct their own errors, to secure the increasing prosperity of a rapidly increasing people by making justice more and more appear to be good policy, was constant and sublime. At one time, indeed, his faith in popular institutions brought him under a cloud. He believed that no government was so strong and persistent as a popular government. He was sure that the American people would not submit to a dissolution of the Union. He believed with Mr. LINCOLN, in the earlier days of the secession movement, that the “irrepressible conflict” between slavery and freedom could be waged under the peaceful forms of law. In this he was mistaken; but his trust in the strength of a popular government, and in the determination of the people to maintain the Union, was fully justified; and the irrepressible conflict ended, as he foresaw it would end, in the triumph of liberty.

Mr. SEWARD’S temperament inclined him to conciliation, to the settlement of disputes by diplomacy. He was unwilling to draw the sword while a chance remained for securing a settlement without appealing to the stern arbitrament of war. This exposed him to the censure and taunts of others of more ardent and hasty temperament, who yet did not love their country and liberty more than he. His clear perception of the probable scope, duration, and uncertainty of a civil war led him to prefer every honorable means of conciliation to that terrible risk, until that risk was no longer to be averted. It was the fashion among those who differed from him on questions of policy to style him a “trimmer,” a “doctrinaire, ”a“ theorist.” But his great and successful career as Secretary of State during the most trying part of our national history forever set that criticism at rest. On all important points of domestic policy it is known that President LINCOLN agreed with him. That he managed our foreign relations with consummate skill is now universally admitted. The task was never more difficult and delicate; it was never more successfully performed. Now that the clouds of partisan animosity are lifted, and his name and career have become the common pride of Americans, it is clear that at a time of unexampled peril, when other nations would have gladly interfered, he held them aloof, and kept the war from assuming proportions and eventualities which the imagination shrinks from picturing.

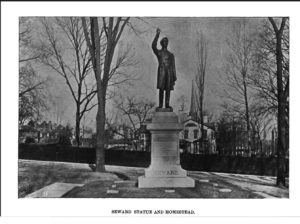

It is pleasant to know that Mr. SEWARD lived to see his name and his career vindicated to the judgment of his countrymen. He was not compelled to leave his fame to the next ages. His noble and illustrious services as a public teacher, boldly asserting the original rights and the natural equality of man, at a time when few were ready to stand by his side, have been clearly recognized. His eminent services as a statesman have been fully acknowledged. Every cloud of distrust, of misappreciation, has been riven by the light of accomplished results; the erroneous judgments of impatience and imperfect knowledge have been reversed. In his quiet retirement at Auburn, where his last years were spent in writing the history of his life, he had the supreme satisfaction of knowing that the great work to which that life had been devoted was accomplished; that liberty had triumphed; that the integrity of the Union was assured forever; and he passed away in the happy consciousness of possessing the love and gratitude of his countrymen.

Page 826:

MR. SEWARD.

“DEATH hath this also,” says BACON, “that it openeth the gate to good fame.” Mr. SEWARD had survived his active career long enough to allow his contemporaries to forecast the judgment of history upon his life and character. A man of great ability and of great sagacity, he lived during great events, and was a conspicuous actor among them. He was the political leader of a moral reform. By temperament an optimist and a doctrinaire, and always intimately associated with men, he won regard by unflagging sweetness and serenity, but he did not command by moral elevation. A statesman by taste and training and ambition, and thrown into the most stormy crisis of the national life, he did not comprehend nor control the deepest force of the situation. He was for many years the most eminent political representative of the anti-slavery movement; but he was drawn to it by personal sympathy and intellectual shrewdness rather than by moral perception or conviction.

A man of the utmost generosity and kindness of heart, the thought of suffering was painful to him—and his defense of the negro FREEMAN showed the depth and swiftness of his sympathy. But he was never technically an Abolitionist. He was a Whig until it was evident that the question of slavery was the really dividing issue, and then he became the advocate of the cause which his shrewd mind showed him must surely triumph. But his optimistic and doctrinaire tendency veiled from him the awful reality of the conflict which in the familiar phrase he described as “irrepressible.” His faith in our popular system was so profound that, with his temperament, he could not believe that it could be seriously assailed; and as he did not comprehend the terrible sincerity of the cause which he represented, he was equally unsuspicious of the grim earnestness of the opposition. In the midst of a speech in the Senate in which with relentless logic he foretold the inevitable disappearance of slavery in the conflict with freedom, he could not understand the faces or the minds of the slave-holders around him, and on one occasion abstractedly put out his hand to Senator BUTLER, of South Carolina, for a pinch of snuff. The Senator handed him his box, but turned away his head, and Mr. SEWARD calmly proceeded, not seeing in that little incident how much more than logic was involved in the debate.

He thought that slavery would be beaten at the polls, and so surrender and peacefully disappear. He smiled at the threats of secession, and believed them to be only moves in a lively political game. In December, 1860, at the New England dinner in New York, he said that the trouble would be over in sixty or ninety days, and he honestly believed it. In his hopeful mind no trouble could last more than ninety days. On the 22d of February, 1861, the flags were flying in Washington, and he said to a colleague, as they walked to the Capitol, “Look at those flags: yet they talk of secession!” And in the same session he believed that his speech would disperse all the lightning of rebellion. From the moment that the civil war began he was bewildered. It was illogical, incomprehensible, a mistake. He fatally misinterpreted its scope in his early instructions to our foreign ministers. But his buoyant temperament floated him above the uproar, and while he clung to M’CLELLAN and opposed the radical policy, he yet believed in success, and never desponded. When the war ended he held the doctrinaire view of the situation. The States had attempted secession. They had failed. Consequently they were as before, with the exception that the war had abolished slavery. Here again he failed to apprehend the fact in his satisfaction with the form. And here, of course, he separated from the party of the war, and his political career ended.

His services to the country were very great, and will not be forgotten. His sagacity showed him when the moment had arrived in which the mass of the Whig party in New York would follow a trusted leader into the antislavery path. He seized the moment, and the Republican party presently appeared. From that time his speeches were the most popularly powerful and instructive and effective in the political anti-slavery propaganda. Calm, forcible, logical, clear, and free from vituperative rhetoric, they were a school in which the people gladly learned. After his bitter disappointment in the nomination of FREMONT in 1856 he made a speech at Detroit, which, in its detailed exposure of the manner in which slavery absolutely possessed the government, from every committee in Congress down to every little post-office in the land, was one of the most valuable speeches ever made in the country. And again, after his disappointment in the nomination of Mr. LINCOLN in 1860, his series of speeches in the West, for their variety, force, animation, and power, are entirely unrivaled in political history, except by the Illinois speeches of LINCOLN in his famous debate with DOUGLAS. To these may be added the California and Kansas speeches in the Senate: for the speeches of a statesman, in a free country, are among his most illustrious and valuable services.

As Secretary of State Mr. SEWARD’S policy was successful, and this fact has perhaps not been adequately recognized. It was an immense service to stay the hand of foreign intervention at that time; and the skillful and masterly correspondence which Mr. ADAMS conducted with Lord RUSSELL was in strict conformity to Mr.SEWARD’S instructions. The Secretary’s letter surrendering SLIDELL and MASON was extremely able. He saved without dispute the honor of his own country while he yielded to the demand of England. In reply to the question what he considered the darkest hour of the war, Mr. SEWARD once said, “That which elapsed between my sending the letter informally to Lord LYONS and hearing from him that it was satisfactory. For I knew that I had gone to the utmost limit that the country would approve, and that if the letter were unsatisfactory to England, we should be at war with her in a month.”

It was Mr. SEWARD’S curious fate to have no part in the crowning triumph of the principles which he had most warmly sustained. By position he was the radical chief before the war, but during its continuance and at its close he was unfriendly to the radical policy. But it is his glory that while WEBSTER and CLAY were strenuous for compromises which were necessarily fatal, SEWARD, remembering BURKE’S question, “Who would barter the immediate jewel of his soul?” nobly said, “I feel the sands of compromise sliding from beneath me, and my feet take hold of the rock of the Constitution.” He had not the weight of WEBSTER nor the grace of CLAY, but his national service was infinitely greater than theirs. He had not their personal magnetism, nor so fond a following; but those who most deeply influence our politics to-day are his pupils, and not theirs. Undaunted in spirit to the last, his life gently ended, and the grave closes over all bitterness of feeling toward him, leaving only the kindly remembrance of his great and patriotic service.