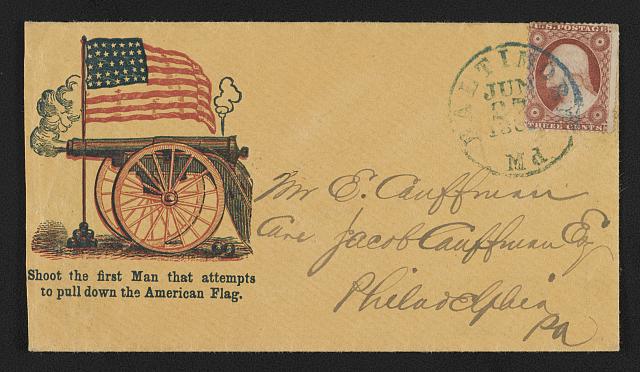

The South had its Fire-Eaters, the North had John A. Dix. While briefly serving as U.S. Secretary of the Treasury for a time before Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration, John Dix sent a telegram to Treasury agents in New Orleans ordering them to shoot on the spot anyone who tried to pull down the United States flag. The telegram never made it to the agents, but the northern press publicized the contents, which fired up Northerners.

It was more peaceful at the state capitol in Albany nearly twelve years later when General Dix was inaugurated governor of New York.

From the January 18, 1873 issue of Harper’s Weekly:

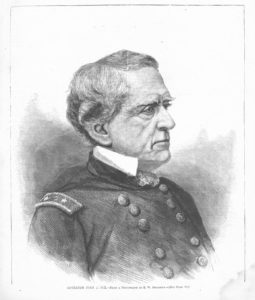

GOVERNOR JOHN A. DIX.

GENERAL JOHN A. Dix, with whose long and eminent career in the civil and military service of the country every reader is familiar, was on the first day of the new year inaugurated as Governor of the Empire State. The ceremonies on this occasion were simple, brief, and impressive. There was very little display, and nothing in the general aspect of the capital to indicate that the Chief Magistrate of five millions of people had given place to his successor, and that a powerful political party had been supplanted by another in the control of the State government.

The retiring Governor entered the Assembly room with General Dix on his arm. The staff of each in full uniform followed, arm in arm. In this order the party walked up the middle aisle until the space in front of the clerk’s desk was reached, when they separated, General Dix going to the platform behind the clerk’s desk by the left, and Governor HOFFMAN by the right. The staff officers, twenty-eight in number, ranged themselves in a semicircle in front of the desk, and when, after a moment, the slight bustle which had attended the entrance had subsided, Governor HOFFMAN addressed General Dix in a few well-chosen words, to which the General made a brief reply, alluding only in general terms to political affairs. The oath of office was then administered, and the ceremony of installation, which had lasted scarcely twenty minutes, was concluded.

Governor Dix, of whom we give a portrait on our first page, enters upon his term of office with the full confidence of the people that he will, to the best of his ability, carry out the policy of reform so emphatically indorsed at the late election.

John A. Dix had a full and varied career, which began as a twelve year old soldier in the War of 1812. From the August 2, 1862 issue of Harper’s Weekly at Son of the South:

MAJOR-GENERAL JOHN A. DIX.

MAJOR-GENERAL JOHN A. Dix, whose portrait we give on page 485, was born in Boscawen, New Hampshire, July 24, 1798. His fattier was the late Colonel Timothy Dix, whose services and death in the last war with Great Britain are matters of history.

In December, 1812, young Dix was appointed’ to a cadetship at the West Point Military Academy; but he never went as pupil to that institution. His father was then in the army, and being stationed in Baltimore, sent for his son, who joined him there, and very soon (March, 1813) received the commission of Ensign, and marched with his father’s command to Sackett’s Harbor, the youngest officer in the American army.

In June, 1813, he was appointed Acting-Adjutant of Major Timothy Upham’s independent battalion of nine companies at Sackett’s Harbor. He accompanied his father in the expedition down the St. Lawrence, and was with him when he died on board one of the transports near French Mills, in November, 1813, after the battle of Chrystler’s Fields. He was then transferred from the infantry to the artillery, and attached to the staff of Colonel Walbach. At the close of the war he remained in the army, part of the time on garrison duty at various stations, from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to Fort Washington and Old Point Comfort, Virginia, and six years as aid-de-camp to Major-General Brown while he was Commander-in-Chief of the army. He finally left the service in 1828.

He read law with William Wirt, then United States Attorney-General, was admitted to the New York bar in 1828, and afterward to the United States bar in Washington.

1849. He was Chairman of the Committee on Commerce, and an active member of the Committee on Military affairs. He was the author of the warehousing system as it was adopted by Congress.

In 1826 he married the adopted daughter of the Hon. John J. Morgan, of New York, by whom he has had four sons and two daughters.

From 1828 to 1831 he practiced law in Cooperstown, New York. In 1831, on being appointed Adjutant-General of the State, he removed to Albany. In 1833 he was chosen Secretary of State and Regent of the University.

In 1841 and 1812 [1842?] General Dix was a member of the New York Assembly from Albany County, and took an active and influential part in the most important legislative measures of that period—such as the liquidation of the State debt by taxation, and the establishment of single Congressional Districts.

On the election of Silas Wright as Governor of New York General Dix was chosen to complete his unexpired term of five years in the United States Senate, and took his seat in that body January 27, 1845, where he remained until March 4, 1849. He was Chairman of the Committee on Commerce, and an active member of the Committee on Military affairs. He was the author of the warehousing system as it was adopted by Congress.

General Dix acted with that portion of the New York Democracy known as “the Free-Soil Democracy” in 1848-’49, and was their candidate for Governor in 1848. But when the delegation of New York became legitimately connected with the nomination of General Pierce for the Presidency in 1852, General Dix sustained that nomination.

On the election of General Pierce to the Presidency he first selected General Dix for his Secretary of State. But, as is well known, the leaders of the Southern democracy, of the Mason and Slidell school, protested so violently against his appointment that it was never made. The same influence prevented his appointment as Minister to France, which had been offered to him as an inducement for him to accept for a while the local office of Assistant-Treasurer of the United States in the city of New York. On the appointment of Mr. John Y. Mason, of Virginia, to the French embassy Mr. Dix resigned the office of Assistant-Treasurer, and withdrew almost wholly from politics.

Early in 1859 enormous defalcations having been discovered in the New York City Post-office, and the defaulting Postmaster having absconded, President Buchanan appointed General Dix to that office, and urged its acceptance on the ground that the public interests required the appointment of some man of the highest character and reputation for integrity and administrative ability. Mr. Dix yielded to these representations, and accepted the office. In January, 1861, the treachery and dishonesty of Floyd, Cobb, & Co., of the first Buchanan Cabinet, having reached their climax, and ended in the withdrawal or flight of those traitors from Washington, and the financial embarrassments of the Government requiring the appointment of a Secretary of the Treasury in whose probity, patriotism, skill, and efficiency the whole country could and would confide, General Dix was called to that high office, and entered on its duties January 15, 1861.

Early in 1859 enormous defalcations having been discovered in the New York City Post-office, and the defaulting Postmaster having absconded, President Buchanan appointed General Dix to that office, and urged its acceptance on the ground that the public interests required the appointment of some man of the highest character and reputation for integrity and administrative ability. Mr. Dix yielded to these representations, and accepted the office. In January, 1861, the treachery and dishonesty of Floyd, Cobb, & Co., of the first Buchanan Cabinet, having reached their climax, and ended in the withdrawal or flight of those traitors from Washington, and the financial embarrassments of the Government requiring the appointment of a Secretary of the Treasury in whose probity, patriotism, skill, and efficiency the whole country could and would confide, General Dix was called to that high office, and entered on its duties January 15, 1861.

On the 18th January, 1861, three days after General Dix took charge of the Treasury Department, he sent a special agent to New Orleans and Mobile for the purpose of saving the revenue vessels at those ports from seizure by the rebels. The most valuable of these vessels, the Robert McClelland, at New Orleans, was commanded by Captain John G. Breshwood, with S. B. Caldwell as his lieutenant. Breshwood refused to obey the orders of General Dix’s agent, Mr. Jones; and on being informed of this refusal, the Secretary telegraphed as follows; “If any man pulls down the American flag, shoot him on the spot!”

This dispatch, evidently thrown off fervido animo, and with a pen too hasty to pause for blot or literal correction, was intercepted by the Governor of Alabama, and did not reach Mr. Jones until the joint villainy of Captain Breshwood and the authorities of Louisiana had been consummated by stealing the cutter. It found its way very soon into the newspapers, and it flew over the land like the Highland cross of fire, setting the hearts of the people every where ablaze.

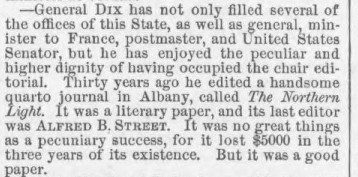

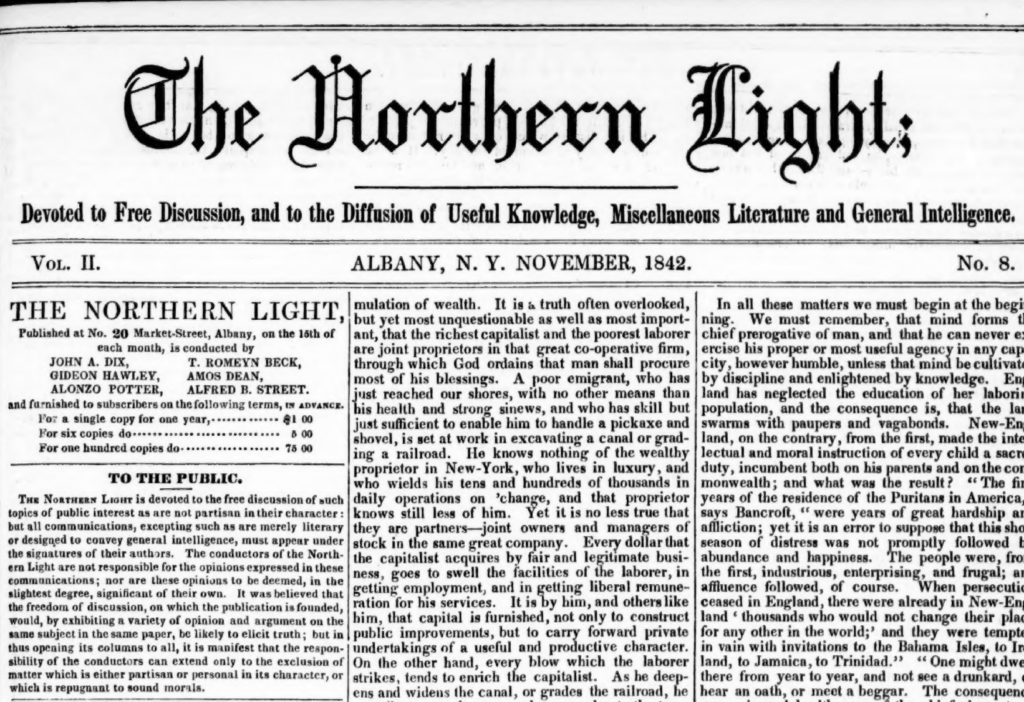

In its January 11, 1873 issue Harper’s Weekly noted yet another job John Dix held, at least for a short time:

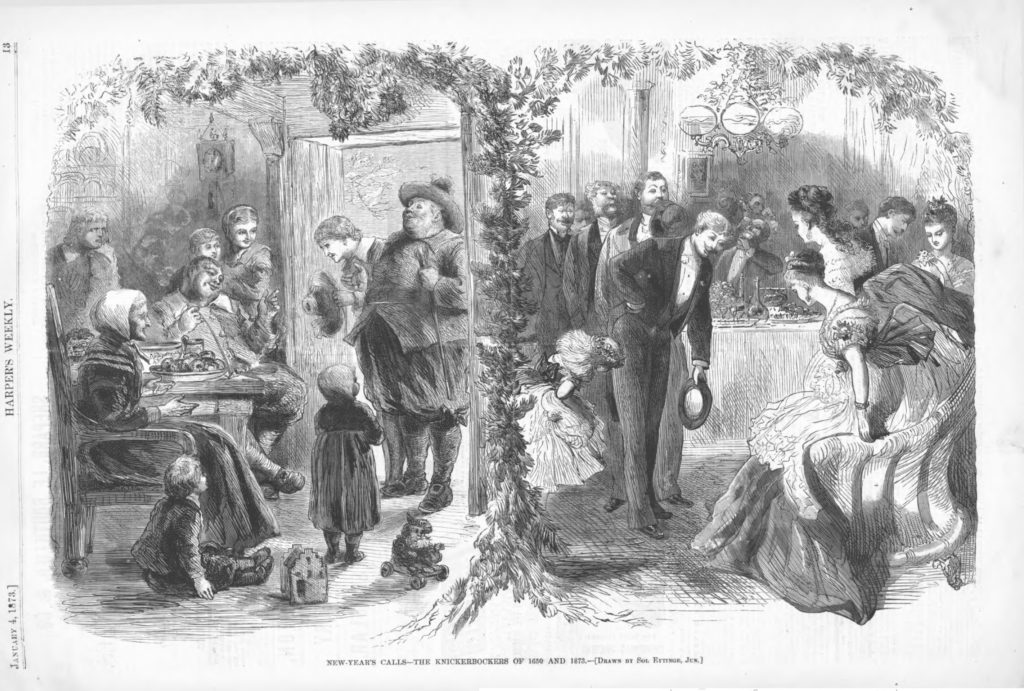

In its January 14, 1873 issue Harper’s Weekly did a historical contrast and compare with a New Year’s Day tradition:

Of course, a lot had changed between 1650 and 1873 for Knickerbockers. In 1664 the English took control of New Amsterdam from the Dutch and renamed it New York. A 1660 map showed the southern tip of the island of Manhattan a few years before the English took over.