NY Times April 8, 1917

A big monument controversy raged a hundred years ago. People objected to a new statue memorializing the Civil War era that they found very offensive. So far I haven’t read about any calls for its dismantling or removal, but some folks sure didn’t want to export any duplicates of it.

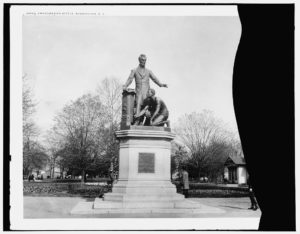

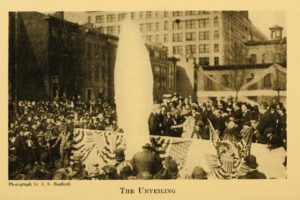

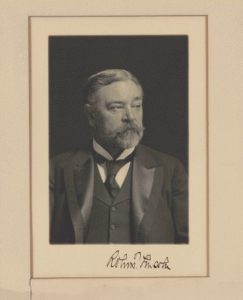

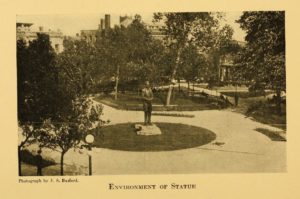

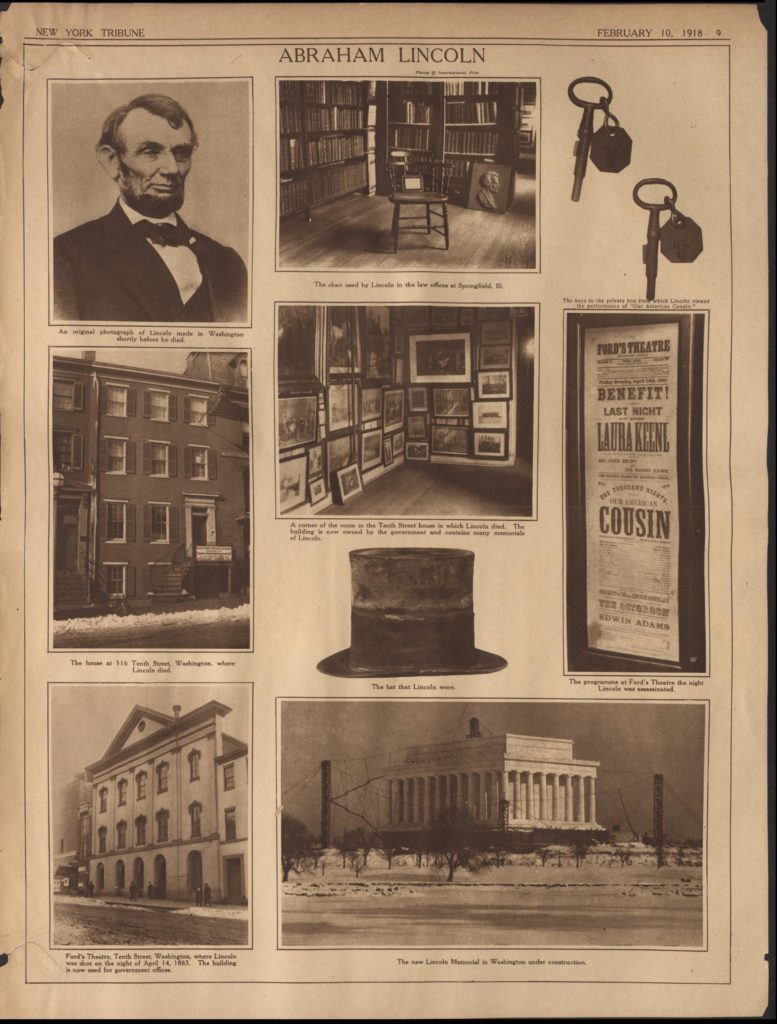

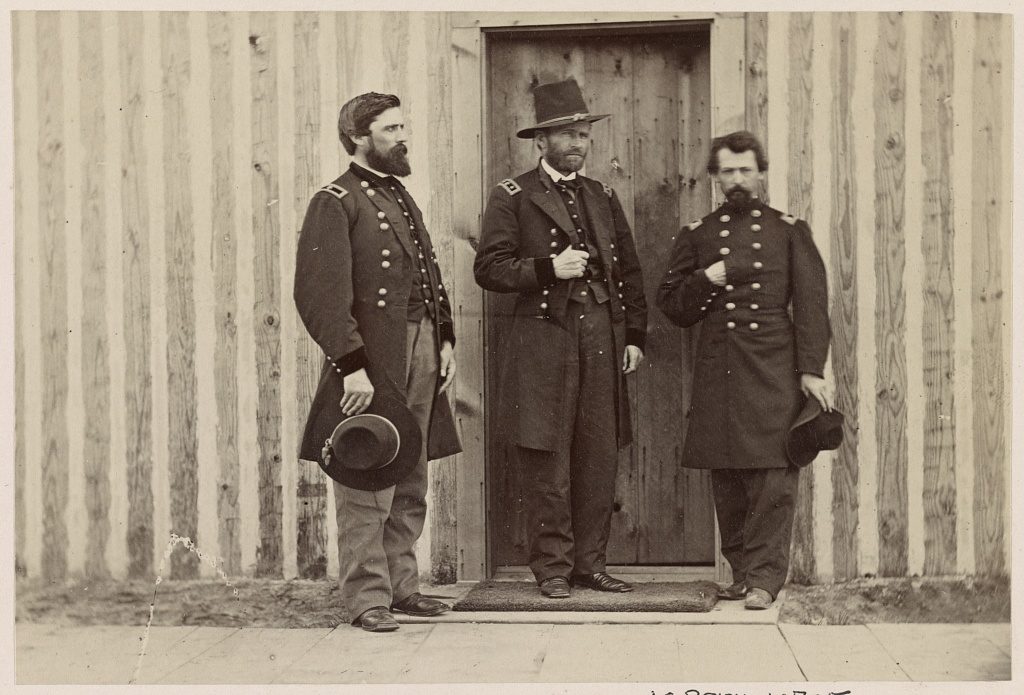

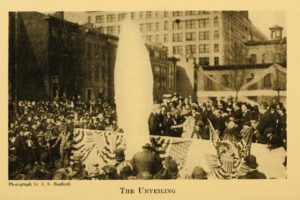

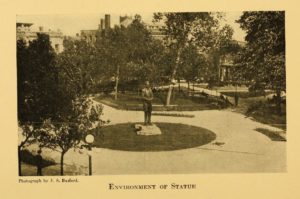

On March 31, 1917 a statue of Abraham Lincoln sculpted by George Grey Barnard was unveiled and dedicated in Cincinnati. The monument was basically a gift from Mr. and Mrs. Charles P. Taft; Mr. Taft’s brother, former president William Howard Taft, delivered the main address.

vision problem?

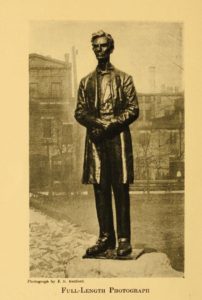

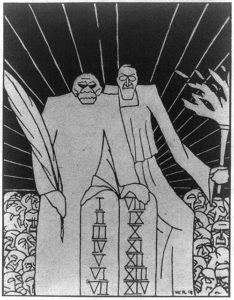

So far so good, but in the autumn of 1917 letters and articles appeared in The New-York Times addressing two questions: was the Barnard statue a decent representation of the sixteenth president’s looks? was it fitting and proper to give duplicates to England and France? People seemed to object to the statue’s hands and feet, the “slouchy” posture, and the unpressed clothes.

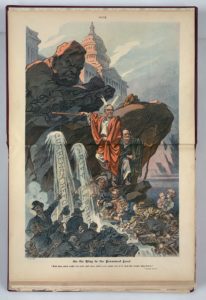

A Times editorial on August 26th explained the issue by endorsing the criticism of Frederick Wellington Ruckstull, “a sculptor and a critic of the fine arts.” The ungainly Lincoln should not be sent to London to be set up in front of Parliament as a representative of “the vigor and the virtue of modern democracy.” President Lincoln was not handsome but his exemplary spirit and will shone through and made him a leader. Barnard’s Lincoln was “a long-suffering peasant, crushed by adversity. His pose is ungainly, the figure lacks dignity, and the huge hands crossed over the stomach suggest that all is not well with his digestion. The largeness of both hands and feet is unduly exaggerated. …”

better left unshown?

Letters to the editor were published from those who knew what Mr. Lincoln really looked like. A 78 year old who lived in Washington at the outbreak of the Civil War remembered the president at White House receptions as looking over the heads of most people who greeted him. “There was no suggestion ever of slouching, gangling, or letting go of himself.” (published October 7th) In another letter to the editor published on October 14th Robert Brewster Stanton wrote that he and his father had many interactions with the president during the war. The then young man had had many opportunities to study the president’s appearance and now found the Barnard statue a “grotesque caricature.” Mr. Lincoln’s pose and attitude overrode the details of his physical appearance, including possibly being “ungainly.” Mr. Stanton was indignant that “the hands that had so often clasped mine with such friendly warmth should ever have been put into the form and position there shown.” In an example of the exception proving the rule, the only time Mr. Stanton only saw President Lincoln “slouchy” was when he was forced to use a public cab with warn out springs in the seat – he could not possibly sit up straight. Should the sculptor have used that image of Lincoln? Don’t send a duplicate of the Cincinnati monument overseas, instead melt it down for bullets for the allies.

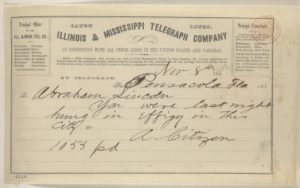

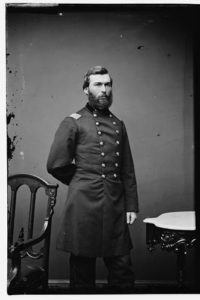

In another Times article, Frederick Wellington Ruckstull, who was also editor of The Art World, defended himself against charges that he had instigated the anti-Barnard campaign. He reproduced letters from several interested parties to prove his point. This included a couple letters from someone who presumably knew Abraham Lincoln even better than Robert Brewster Stanton and who expressed his concern about reproducing the Cincinnati statue even before its unveiling on March 31st. Robert Todd Lincoln, son of Abraham and Mary, wanted ex-President Taft to persuade his brother Charles not to send a duplicate of the Barnard statue overseas.

From The New-York Times September 28, 1917:

Hildene, Manchester, Vt. Sept. 16, 1917.

F. Wellington Ruckstuhl, Esq., Editor The Art World, New York, N.Y.

My Dear Mr. Ruckstuhl:

filial piety

In reply to your suggestion that I should send you for publication a letter of protest against the erection in London and in Paris of the Barnard statue of my father, I find myself in difficulty, owing to the vigor and fullness of your own articles in the June and August issues of The Art World. I have already expressed to you my deep sense of gratification that you have so earnestly dealt with this miserable affair, from both artistic and public points of view, and I can think of nothing to add in those regards. But, as you did not know my own personal feeling and opinion when you kindly sent me your published articles, and think that there are others who might care to know them, I am sending you a copy of a letter written by me to President Taft, as soon as I heard of the London and Paris projects; I send also copies of letters giving the views of three gentlemen peculiarly able to express a personal opinion for reasons I indicate in notes appended to the copies. These you are at liberty to use as you may think proper.

Renewing my thanks to you for the helpful part you are taking in my efforts, believe me, very sincerely yours,

(Signed) ROBERT LINCOLN.

Mr. Ruckstuhl also gave out a copy of the letter Mr. Lincoln had written to Mr. Taft. It was as follows:

1.775[?] N Street,

Washington, D.C.

March 22, 1917.

My Dear Mr. President:

I am writing to ask your consideration of a matter which is giving me great concern and to bespeak such assistance as you feel able to give me.

monster in the ‘hood

When I first learned through the newspapers that your brother, Mr. Charles P. Taft, had caused to be made a large statue of my father for presentation to the City of Cincinnati I very naturally most gratefully appreciated the sentiment which moved him to do this; when, however, the statue was exhibited early this Winter I was deeply grieved by the result of the commission which Mr. Taft had given to Mr. Barnard. I could not understand, and still do not understand, any rational basis for such a work as he has produced. I have seen some of the newspaper publications inspired by him, one of which, printed in The North American of Philadelphia in November, and another in The Literary Digest for Jan. 6 last, attempt to make explanations which are anything but satisfactory, to me at least. He indicates, if I can understand him, that he scorned the use of the many existing photographs of President Lincoln, and took as a model for his figure a man chosen by him for the curious artistic reasons that he was 6 feet 4½ inches in height, was born on a farm fifteen miles from where Lincoln was born, was about 40 years of age, and had been splitting rails all his life.

The result is a monstrous figure, which is grotesque as a likeness of President Lincoln and defamatory as an effigy.

![[William H. Taft, full-length portrait, standing, facing left, with hand on telephone] (c1908.; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/96521946/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/3a10399v-241x300.jpg)

was asked to lean on his brother

Believe me, my dear Mr. President, always sincerely yours,

(Signed) ROBERT LINCOLN

The Hon. William Howard Taft.

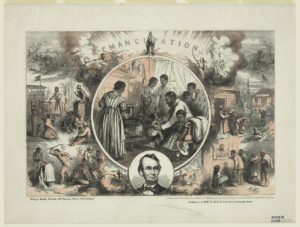

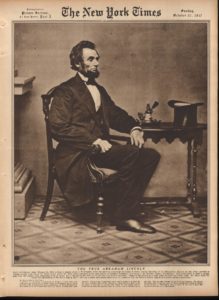

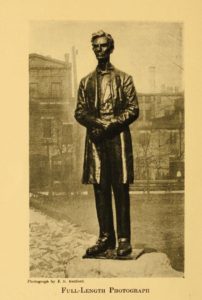

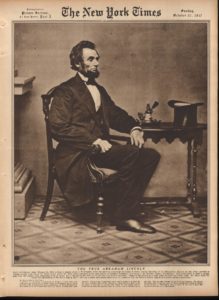

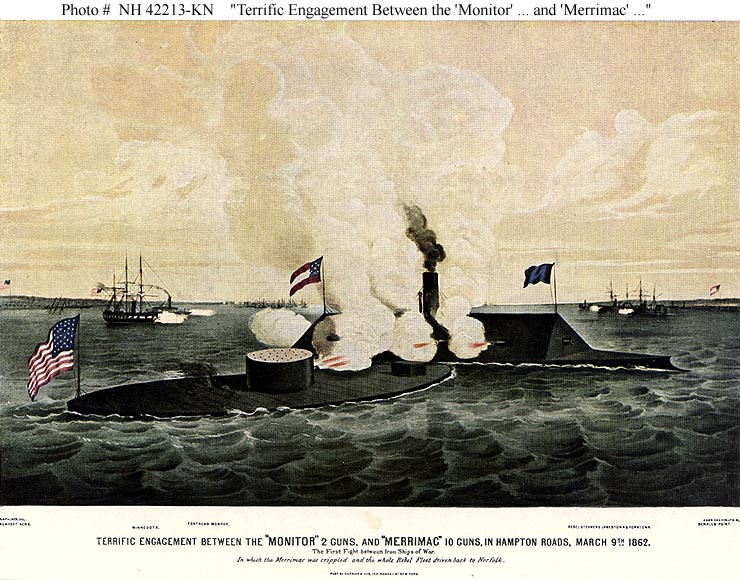

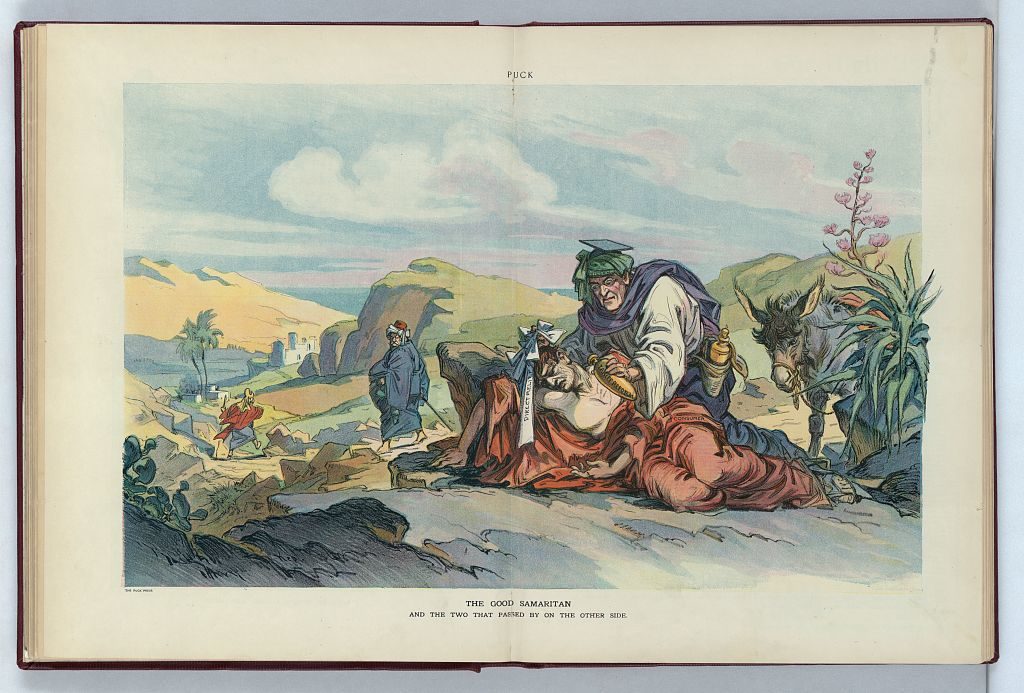

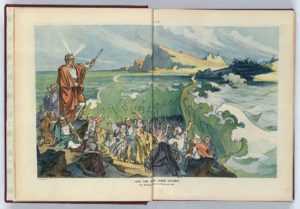

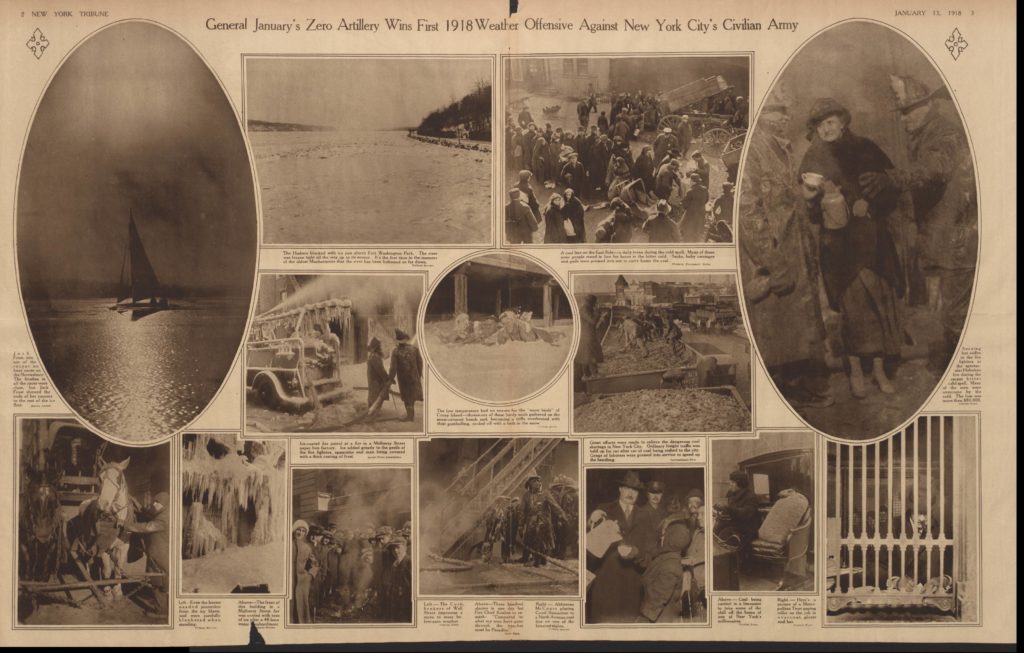

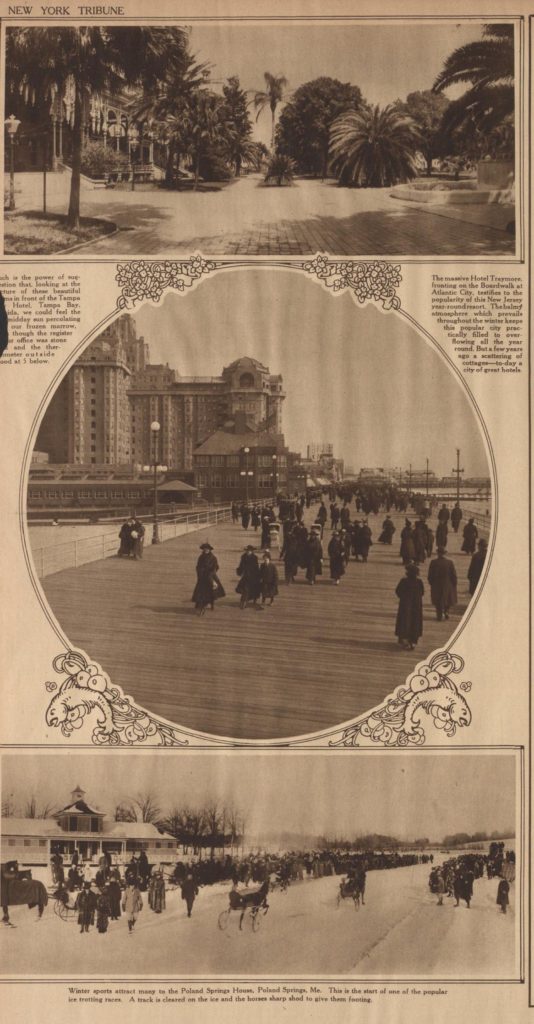

The Times continue to editorialize about the statue controversy. On October 3, 1917 the paper maintained that the proper Lincoln to stand with great British leaders “should faithfully and sympathetically depict the ideal of the Emancipator, the heroic, self-sacrificing American leader who bore so bravely the great burden of his nation’s troubles.” In addition the newspaper provided a couple images for its Sunday picture section that contributed useful information.

true photo

Borglum’s take

_______________________________

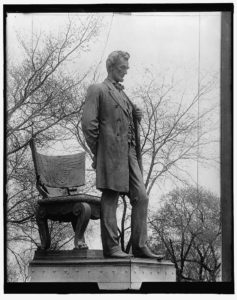

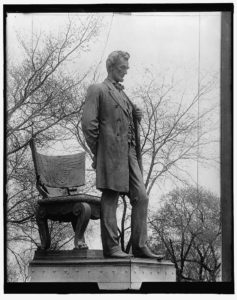

In an article on October 28th the Times published an analysis by Kenyon Cox. The painter understood what Mr. Barnard was trying to achieve artistically with the Cincinnati statue, but “Neither as portrait nor symbol … does the Barnard statue represent the real Lincoln as seen in his photographs and held in the hearts of the people of America.” Mr. Cox didn’t want either Barnard’s statue or Borglum’s Newark statue duplicated for Europe. Instead he plunked for a third option – the statue in Lincoln Park, Chicago by Augustus Saint-Gaudens. The article contained photos of the the three sculptures and the above photograph taken just before Lincoln’s inauguration.

The artist himself wrote a letter to the editor, which the Times included in a November 18, 1917 mini-editorial mostly critical of Mr. Barnard and his Lincoln:

no beauty

… To the Editor of The New York Times:

These lines, my only answer, are worthy, I hope, to be placed on your editorial page:

“For he shall grow up before him

“as a tender plant, and as a root out

“of a dry ground: he hath no form

“nor comeliness; and when we shall

“see him, there is no beauty that we

“should desire him.

“He is despised and rejected of

“men; a man of sorrows, and ac-

“quainted with grief: and we hid as

“it were our faces from him; he was

“despised, and we esteemed him not.”

– Isaiah liii.

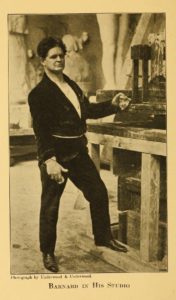

GEORGE GREY BARNARD …

The British, for their part, responded very diplomatically to the controversy. A couple articles in September 1917 reported that British representatives wanted to leave the decision of which duplicate monument to deliver up to the Americans. Here’s an example from The New-York Times September 25, 1917:

AWAIT BARNARD’S LINCOLN.

British Leave Criticism of Statue

to the American Committee.

Special Cable to THE NEW YORK TIMES.

LONDON, Sept.24. – Art Circles here are startled by the cabled criticisms of the Barnard statue of Lincoln which is to be erected here as a gift in commemoration of the hundred years of peace between England and the United States.

The British Government is providing a magnificent site near the House of lords.

The question of the artistic character of the statue is held to be one for the American committee to consider, not the British authorities, whose only desire is to commemorate Lincoln worthily.

Saint-Gaudens Lincoln in Lincoln Park, Chicago

Furthermore, the British would be happy to take both statues. In an article on October 21, 1917 the British-American Centenary Committee explained that in 1913 it had been agreed that Britain would accept the St. Gaudens Chicago Lincoln replica. The outbreak of the war in Europe temporarily suspended the peace centenary movement and the St. Gaudens project ended. The committee accepted Charles P. Taft’s offer of the Barnard statue replica earlier in 1917. However, both statues would be accepted if the St. Gaudens project could be funded:” “There is room in Great Britain – yes, in London – for more than one monument of America’s saint and hero President, whose memory all Englishmen revere and love.”

Barnard not doing patriot’s work?

As the year turned, the controversy continued, but progress towards a resolution seemed possible. In an article on January 2, 1918 The New-York Times indicated that Americans were communicating with the British to explain that Americans really didn’t like or want to donate a replica of the Cincinnati statue, “that Colossal Clodhopper in a Fit of Indigestion called by Mr. GEORGE GREY BARNARD ‘Lincoln.'” Experts, a consensus of artists, Robert Todd, those others who knew what Mr. Lincoln looked like, and those who knew his qualities that should be commemorated all disapproved “this queer, gigantic effigy of Somebody from Kentucky.” The British understandably didn’t want to offend the American Peace Centenary Committee, but that committee had recently held a meeting in which only two of sixty members were at all in favor the the Barnard statue. Even the donor Charles P. Taft might have been the victim of the false impression that people liked the Barnard. Another article mentioned that Colonel Theodore Roosevelt was one of the most prominent friends of the National Academy of Design, which opposed the Barnard statue along with Robert Todd Lincoln, Joseph H. Choate, and Henry Cabot Lodge.

My name is

Abraham Lincoln

My name is

Abraham Lincoln

My name is

Abraham Lincoln

As far as I can tell no final decision had been made about which duplicate to send to London had been made by the end of January 1918, but I’ll probably keep checking.

My first reaction when I learned about the controversy was – America wanted to commemorate British-American friendship by sending a replica to London? But I’ve changed me mind a bit – after all, who wouldn’t want an exact duplicate of Mount Rushmore in their home?

I don’t know how posed that photo of Borglum’s statue in Newark was, but I sure enjoyed seeing it. You can get a quick view of the monument and a poem at Youtube. John Gutzon de la Mothe Borglum supervised the Mount Rushmore project.

Thanks to Youtube I found out how faulty my memory can be. I enjoyed watching To Tell the Truth as a kid. I remembered the tagline being “I am Abraham Lincoln,” but apparently sometimes the contestants said “My name is …” and sometimes they didn’t say anything during the intro. I had another of those jaw-dropping moments when I saw one of the Youtube titles Mt. Rushmore sculptor. I want to investigate that – no one looked like Gutzon Borglum in the introduction; I’m also interested in an episode about a fellow named Orville Redenbacher. I’ve seem to have this unaccountable urge while away a winter afternoon with To Tell the Truth, popcorn, and a big slurp of some kind of beverage.

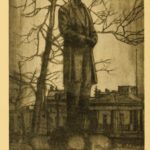

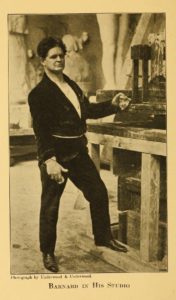

All the images pertaining to George Grey Barnard and his statue of Mr. Lincoln were published in Barnard’s Lincoln and can be seen at HathiTrust. The book includes Mr. Barnard’s explanation of how and why he chose to portray Abraham Lincoln as he did. You can also read William H. Taft’s address at the unveiling in Cincinnati and a poem by Dr. Lyman Whitney Allen. Robert C. Clowry vouched for the statue’s likeness to Lincoln. An etching seemed to veil the statue’s pedestal and reminded me a bit of Pig-Pen on Peanuts.

obscurantism?

detailing “a symbol of democracy”

(from the poem)

clean-shaven in Springfield

From the Library of Congress: unveiling; The Emancipator’s son; William Howard Taft; Mr. Story’s photograph; Newark’s kid magnet; in Chicago’s Lincoln Park solo and with scouts; Colonel Roosevelt and ship workers. On May 30, 1922 Robert Todd Lincoln attended the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. (Daniel Chester French presumably designed a more attractive Lincoln) – snapeshot, with presidents.

![[Boy's Clubs in front of Lincoln National Monument, Illinois making the scout's honor sign and presenting a wreath. Copy 2.] (LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/scsm000890/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/St-Gaudens-Lincoln-Park-150x150.jpg)

“making the scout’s honor sign

and presenting a wreath”

easier on the eyes in D.C.

Taft, Harding, Lincoln

![Portrait of Ulysses S. Grant ([ca. 1865] ; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2004674419/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/3a04853r-224x300.jpg)

![[Secretary of War Edwin Stanton] ([1862]; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2017659637/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/52235v-187x300.jpg)

![Portrait of Andrew Johnson / A. Gardner, photographer, 511 Seventh Street, Washington. ([1866]; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2002736311/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/39463v-230x300.jpg)

![[William H. Taft, full-length portrait, standing, facing left, with hand on telephone] (c1908.; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/96521946/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/3a10399v-241x300.jpg)

![[Boy's Clubs in front of Lincoln National Monument, Illinois making the scout's honor sign and presenting a wreath. Copy 2.] (LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/scsm000890/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/St-Gaudens-Lincoln-Park-150x150.jpg)

![[Martin Luther King, Jr., Memorial, Washington, D.C. The promissory note] / Christopher Grubbs, illustrator. (LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2016647751/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/MLK.jpg)

![Momentaufnahme von Europa und Halbasien 1914 / W. Kaspar fec. (Hamburg : Lith. Druck u. Verlag von Graht & Kaspar, Hamburg 6. 1. 7788, [1915?]; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2014648402/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/01408v-300x223.jpg)

![Carte symbolique de l'Europe Guerre libératrice de 1914-1915 / / B. Crétée, 1914. ([Paris] : Éditions G.D., [1915]; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2016647864/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/41006v-300x250.jpg)

![Webster's note and draft calendar for the years 1866, 1867 & 1868. [n. p. c1866]. (1866; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/rbpe.0720200a/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Leap-Day-1868-300x203.jpg)

![New Year's calls ([New York, N.Y.] : [George Stacy], [between 1861 and 1866]; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2017647818/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/1s05171v-1024x521.jpg)